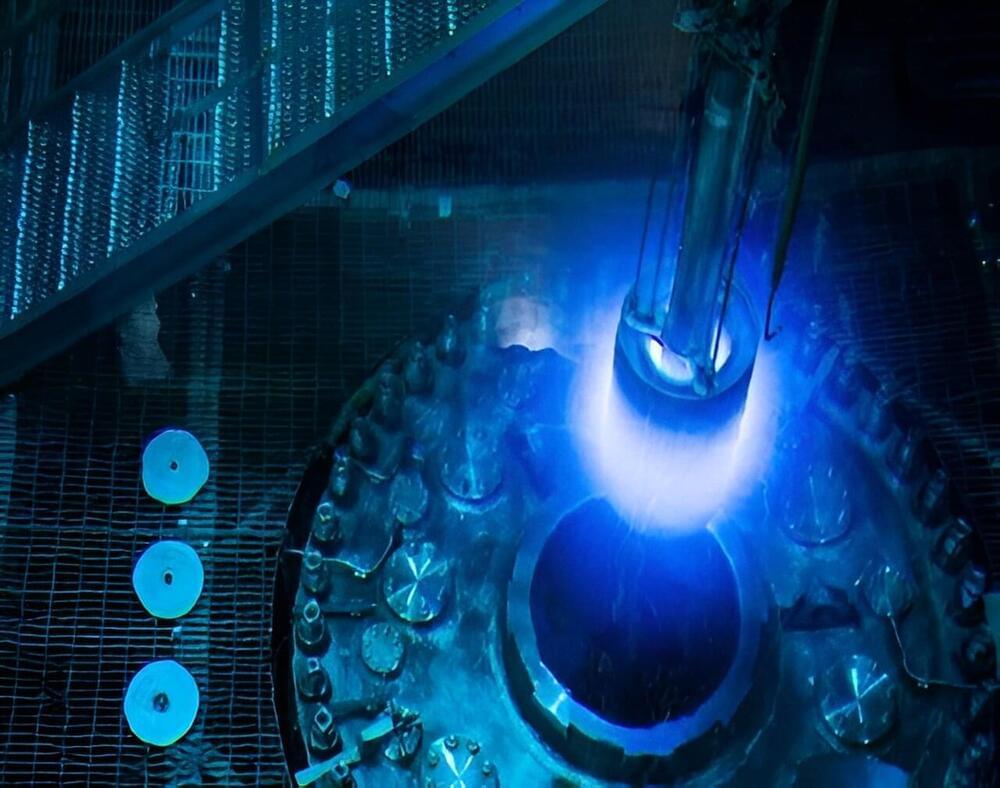

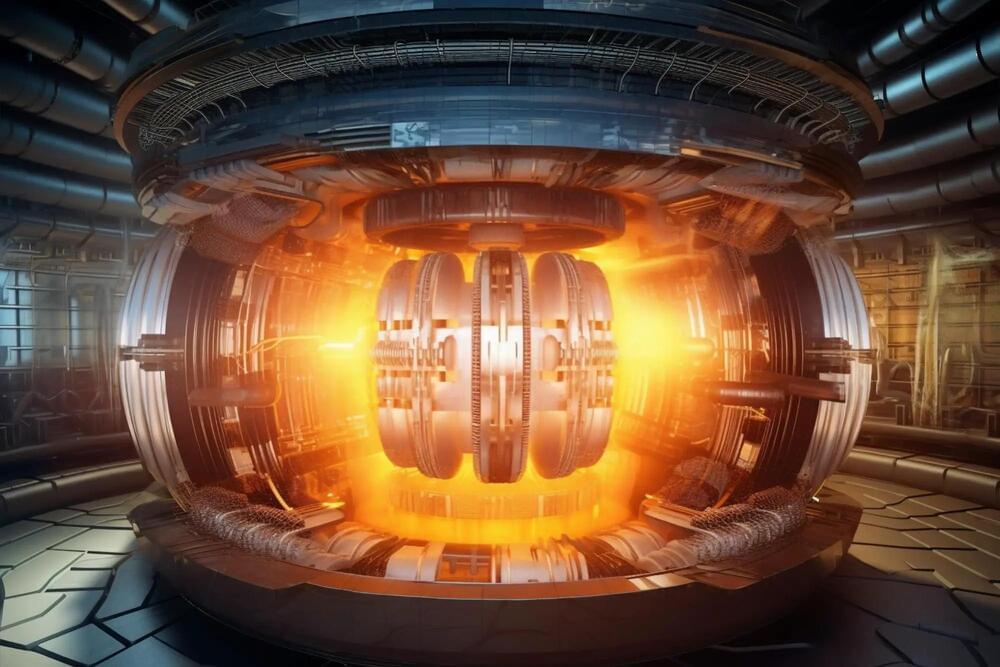

Nuclear fusion holds the promise to generate energy in a clean, safe, and nearly inexhaustible way. The physical idea of fusion involves confining fuels at unearthly temperatures of approximately 150,000,000 degree Celsius which fusion reactions between atomic nuclei can happen. The fuels of interest, deuterium and tritium (isotopes of hydrogen), exist in the state of plasma. Clearly, containing these extremely hot plasmas with solid walls is unfeasible.

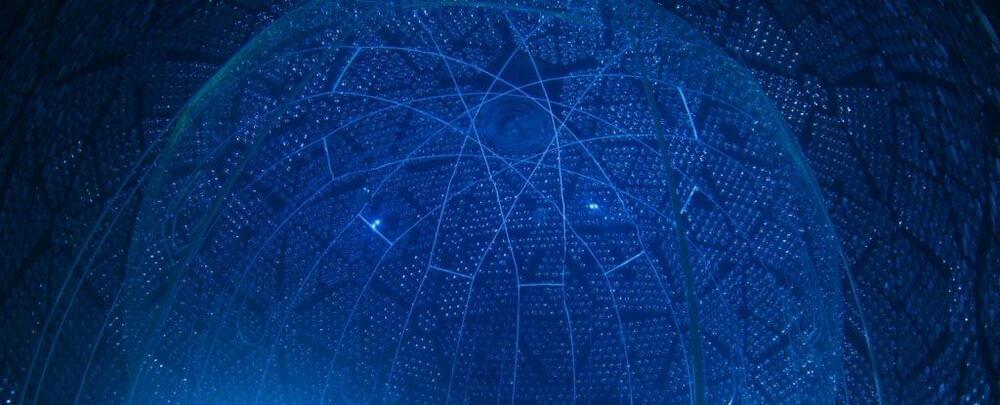

A plasma is an ionised gas comprising charged particles, both ions and electrons. Fortunately, the dynamics of charge particles are subject to constraints along magnetic field lines. This insight forms the basis of our current approach: constructing a magnetic bottle using powerful magnetic fields that effectively trap the plasma along these intangible field lines.

One of the most iconic magnetic confinement machine designs is the tokamak — a toroidally-shaped device, often likened to a doughnut. The name ‘tokamak’ is derived from the Russian acronym for ‘to roidal cha mber with ma gnetic c oils.’