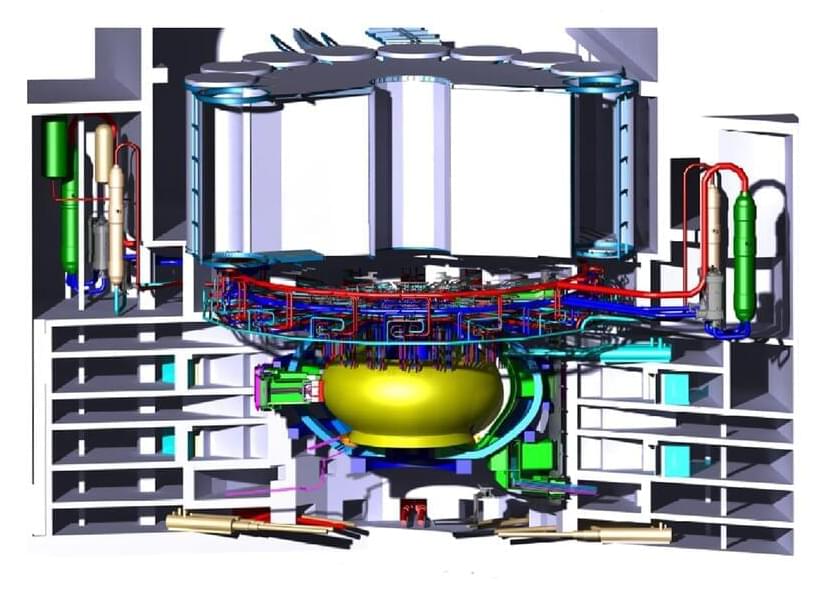

Avalanche is a VC-backed, fusion energy start-up based in Seattle, WA. They are designing, testing and building micro-fusion reactors that you can hold in your hand. Their modular reactor design can be stacked for endless power applications and unprecedented energy density to provide clean energy and decarbonize the planet.

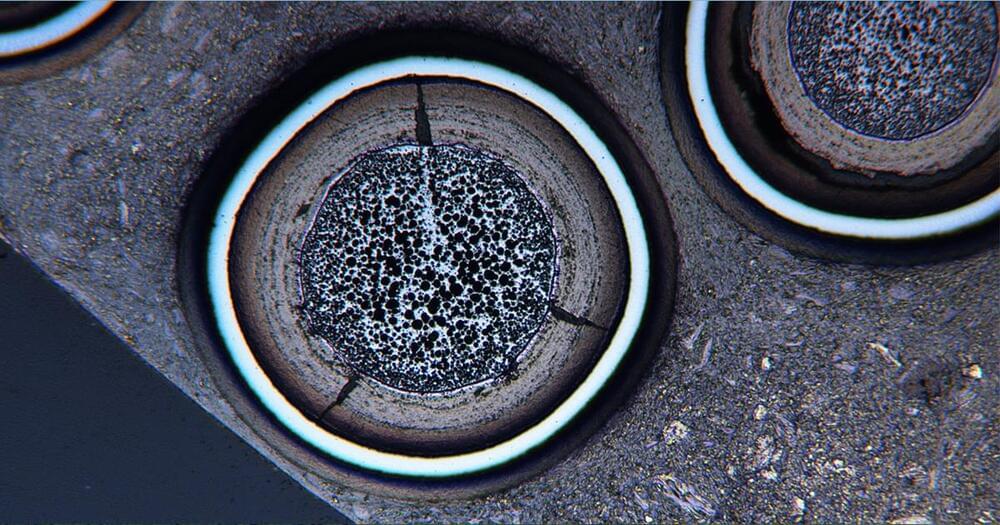

Avalanche is developing a 5kWe power pack called the “Orbitron” in a form-factor the size of a lunch pail. The unique physics of the Orbitron allows for its compact size which is a key enabler for development, scaling, and a wide variety of applications. Avalanche Energy uses electrostatic fields to trap fusion ions and also uses a magnetron electron confinement to reach higher ion densities. The resulting fusion reaction produces neutrons that can be transformed into heat.

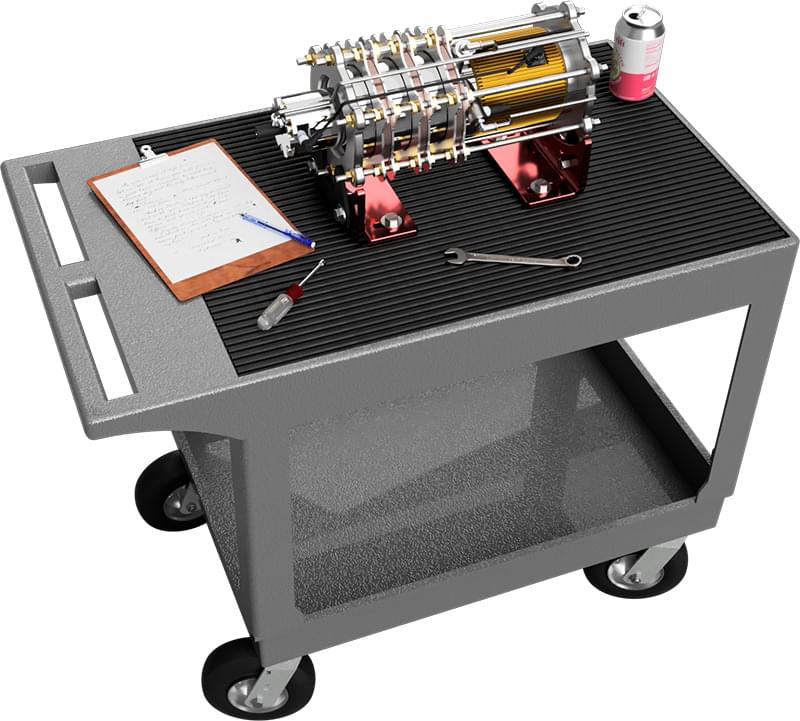

The magnetron is a variation of a component in regular microwave ovens and the electrostatic base technology is a derivative of a product available from ThermoFisher Scientific, which is widely deployed for use in commercial mass spectrometry. They are taking two devices that exist already, things you can buy commercially for various applications. They are putting them together in a new interesting way at much higher voltages” to build a “recirculating beam fusion” prototype.