Silicon semiconductors are widely used as particle detectors; however, their long-term operation is constrained by performance degradation in high-radiation environments. Researchers at University of Tsukuba have demonstrated real-time, two-dimensional position detection of individual charged particles using a gallium nitride (GaN) semiconductor with superior radiation tolerance.

Silicon (Si)-based devices are widely used in electrical and electronic applications; however, prolonged exposure to high radiation doses leads to performance degradation, malfunction, and eventual failure. These limitations create a strong demand for alternative semiconductor materials capable of operating reliably in harsh environments, including high-energy accelerator experiments, nuclear-reactor containment systems, and long-duration lunar or deep-space missions.

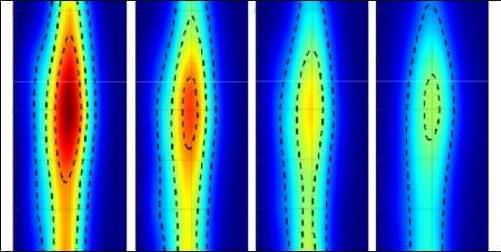

Wide-bandgap semiconductors, characterized by strong atomic bonding, offer the radiation tolerance required under such conditions. Among these materials, gallium nitride (GaN)—commonly employed in blue light-emitting diodes and high-frequency, high-power electronic devices—has not previously been demonstrated in detectors capable of two-dimensional particle-position sensing for particle and nuclear physics applications.