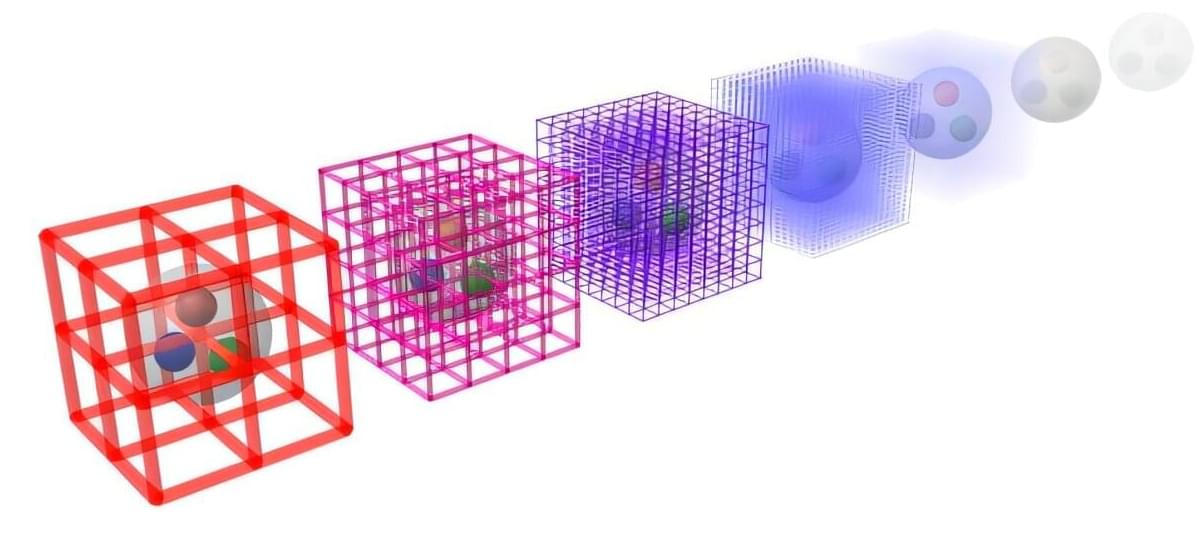

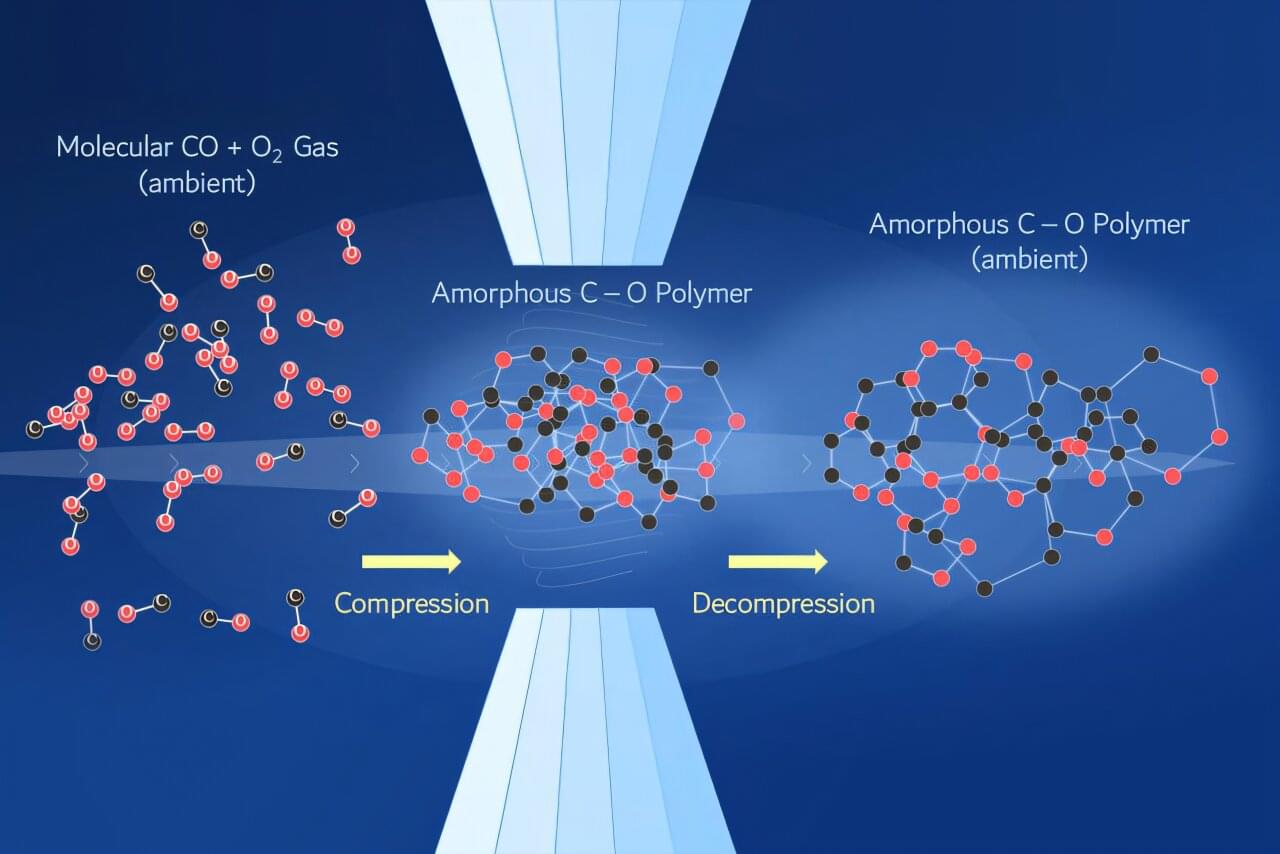

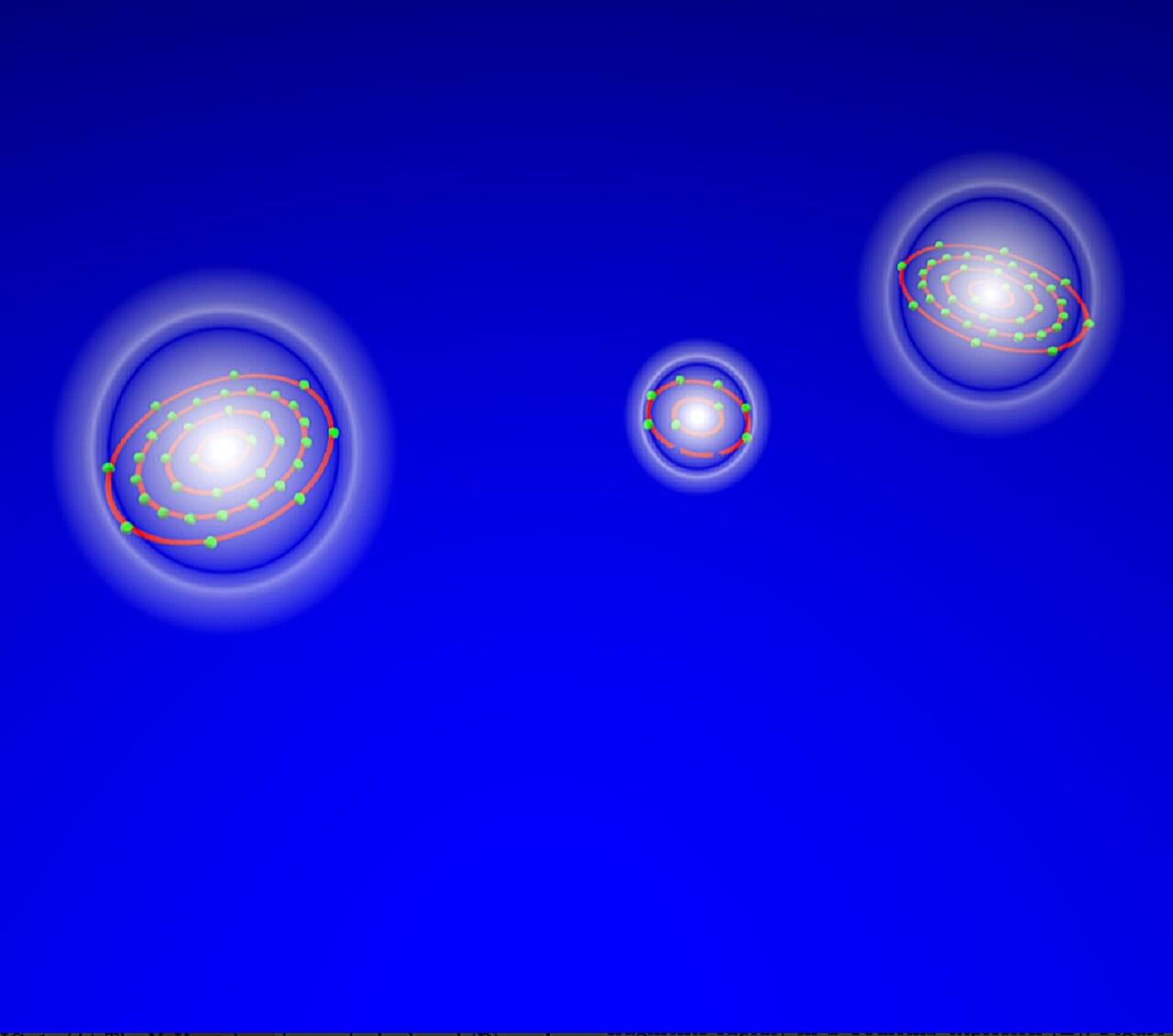

Scientists have built a quantum “wire” where atoms collide endlessly—but energy and motion never slow down. Researchers at TU Wien have discovered a quantum system where energy and mass move with perfect efficiency. In an ultracold gas of atoms confined to a single line, countless collisions occur—but nothing slows down. Instead of diffusing like heat in metal, motion travels cleanly and undiminished, much like a Newton’s cradle. The finding reveals a striking form of transport that breaks the usual rules of resistance.

In everyday physics, transport describes how things move from one place to another. Electric charge flows through wires, heat spreads through metal, and water travels through pipes. In each case, scientists can measure how easily charge, energy, or mass moves through a material. Under normal conditions, that movement is slowed by friction and collisions, creating resistance that weakens or eventually stops the flow.

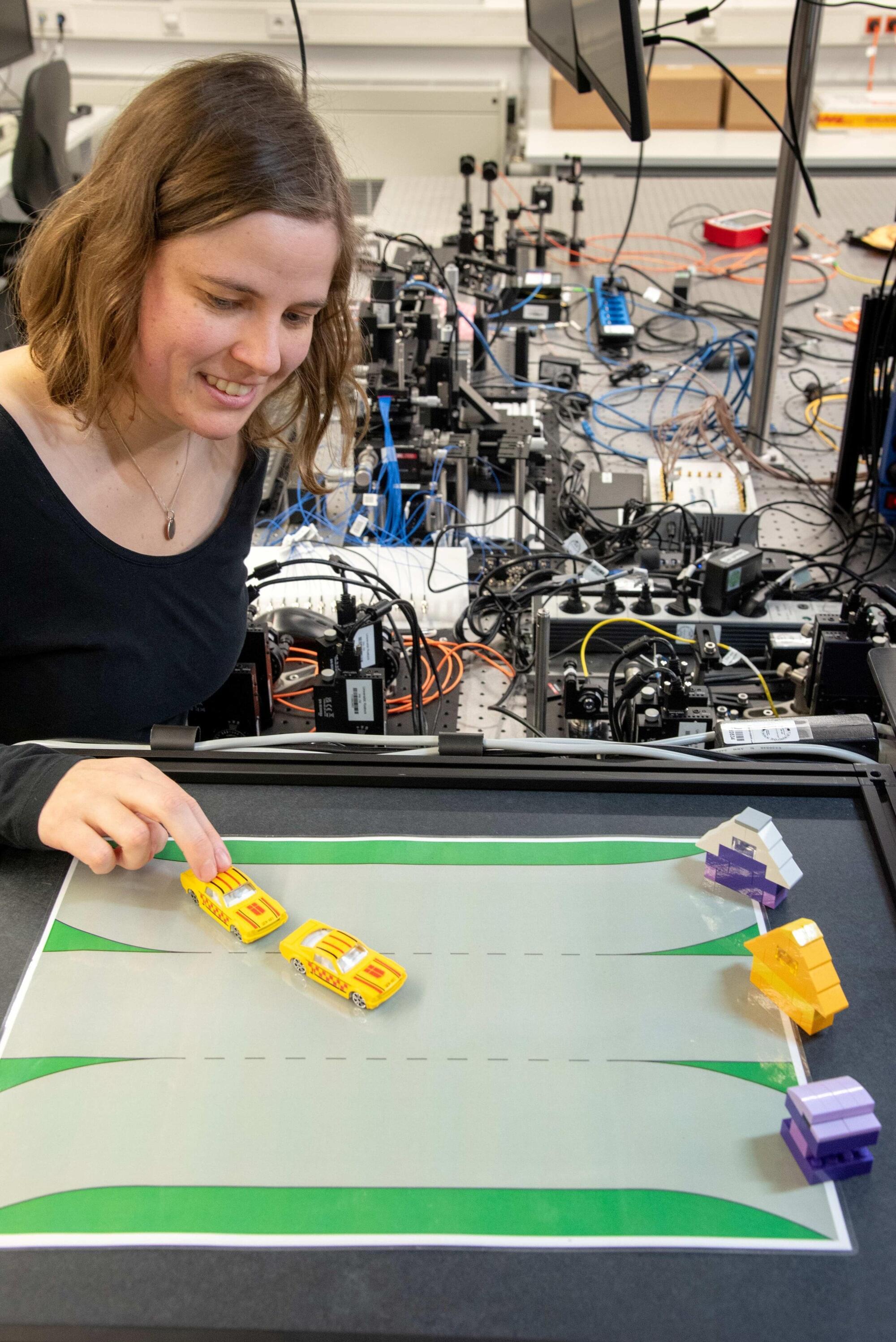

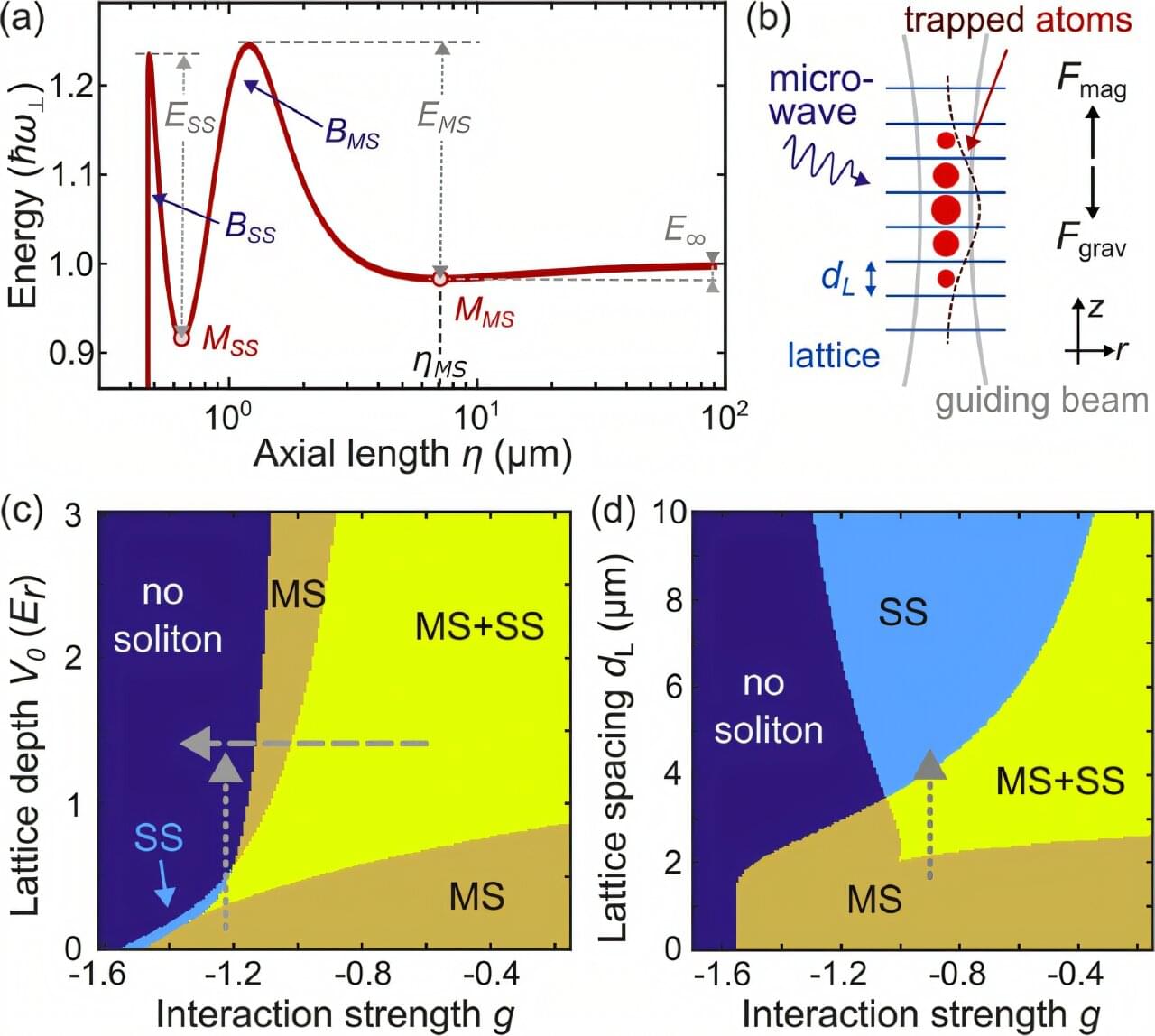

Researchers at TU Wien have now demonstrated a rare exception. In a carefully designed experiment, they observed a physical system in which transport does not degrade at all.