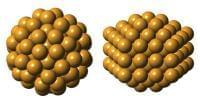

Planck length and Planck time and quantum foam.

Space Emerging from Quantum.

The other day I was amused to find a quote from Einstein, in 1936, about how hard it would be to quantize gravity: “like an attempt to breathe in empty space.” Eight decades later, I think we can still agree that it’s hard.

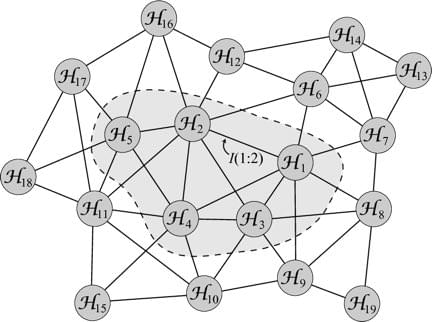

So here is a possibility worth considering: rather than quantizing gravity, maybe we should try to gravitize quantum mechanics. Or, more accurately but less evocatively, “find gravity inside quantum mechanics.” Rather than starting with some essentially classical view of gravity and “quantizing” it, we might imagine starting with a quantum view of reality from the start, and find the ordinary three-dimensional space in which we live somehow emerging from quantum information. That’s the project that ChunJun (Charles) Cao, Spyridon (Spiros) Michalakis, and I take a few tentative steps toward in a new paper.

We human beings, even those who have been studying quantum mechanics for a long time, still think in terms of a classical concepts. Positions, momenta, particles, fields, space itself. Quantum mechanics tells a different story. The quantum state of the universe is not a collection of things distributed through space, but something called a wave function. The wave function gives us a way of calculating the outcomes of measurements: whenever we measure an observable quantity like the position or momentum or spin of a particle, the wave function has a value for every possible outcome, and the probability of obtaining that outcome is given by the wave function squared. Indeed, that’s typically how we construct wave functions in practice. Start with some classical-sounding notion like “the position of a particle” or “the amplitude of a field,” and to each possible value we attach a complex number.