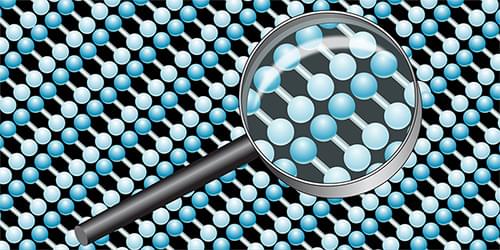

Contrary to widespread belief, our Moon does have an atmosphere, albeit extremely thin and officially known as an “exosphere”. But what are the processes responsible for forming and maintaining this exosphere, which have eluded scientists for some time? This is what a recent study published in Science Advances hopes to address as a team of researchers investigated how a phenomenon known as “impact vaporization” from the surface being hit my objects ranging from micrometeoroids to massive meteorites during its recent and ancient history, respectively. This study holds the potential to help scientists better understand the formation and evolution of planetary bodies throughout the solar system and the processes that maintain them today.

For the study, the team analyzed 10 Apollo lunar samples (one volcanic and nine lunar regolith aka “lunar soil”) collected by astronauts over five landing sites with the goal of ascertaining how much space weathering they’ve endured over the Moon’s long history. This is because when an impact occurs, this causes the specific atoms to vaporize and kick up portions of this material into space while other portions remain trapped by lunar gravity, although now orbiting the Moon. In the end, the researchers discovered that impact vaporization is the main process responsible for the lunar exosphere over the several billion-year history of the Moon.

“We give a definitive answer that meteorite impact vaporization is the dominant process that creates the lunar atmosphere,” said Dr. Nicole Nie, who is an assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences and lead author of the study. “The moon is close to 4.5 billion years old, and through that time the surface has been continuously bombarded by meteorites. We show that eventually, a thin atmosphere reaches a steady state because it’s being continuously replenished by small impacts all over the moon.”