🔗 Top quark and top antiquark entanglement 🔗

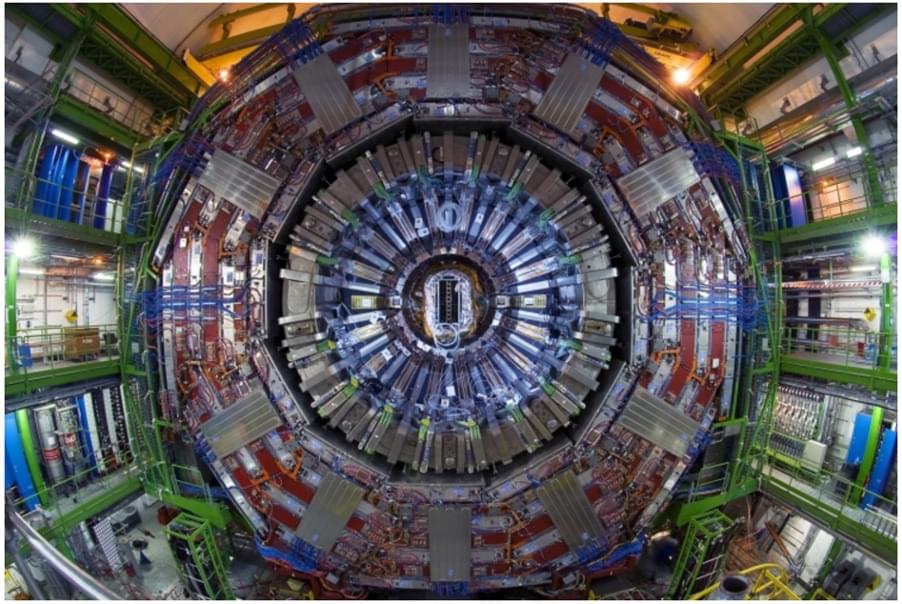

The CMS experiment has just reported the observation and confirms the existence of #entanglement between the top #quark and its #Antiparticle beyond reasonable doubt.

The CMS experiment has just reported the observation of quantum entanglement between a top quark and a top antiquark, simultaneously produced at the LHC.

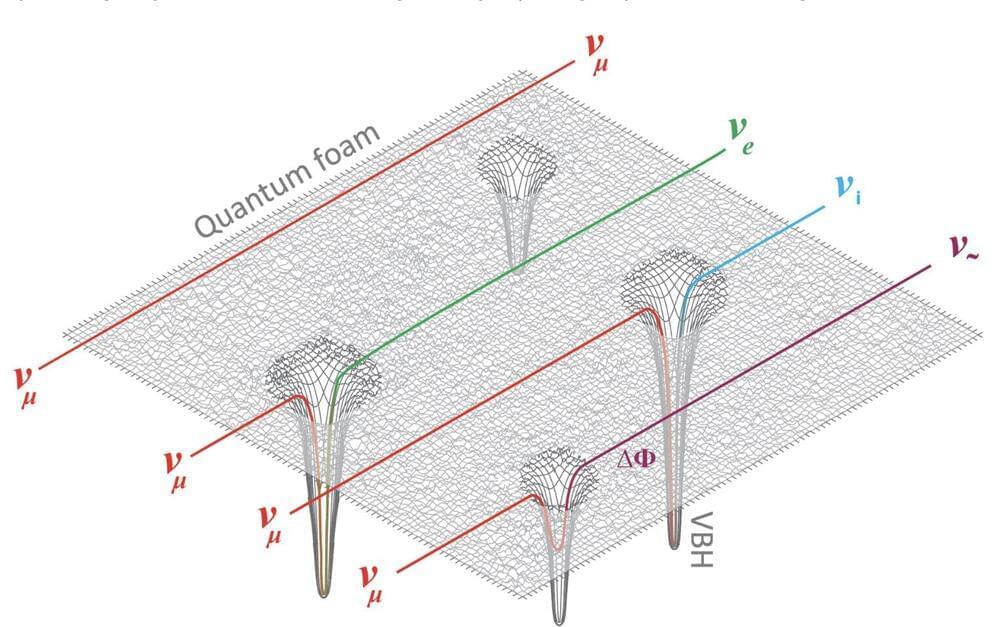

In quantum mechanics, a system is said to be entangled if its quantum state cannot be described as a simple superposition of the states of its constituents. If two particles are entangled, we cannot describe one of them independently of the other, even if the particles are separated by a very large distance. When we measure the quantum state of one of the two particles, we instantly know the state of the other. The information is not transmitted via any physical channel; it is encoded in the correlated two-particle system.

Quantum information is a field of physics that was born with the work of John Bell, a CERN physicist, in the mid 1960’s. Soon after, Aspect, Clouser, and other physicists did important pioneering experimental work to test “Bell’s theorem”, and in 2007 Zeilinger’s team convincingly demonstrated the existence of entanglement between two photons, too far away from each other for the information to travel between them at the speed of light. This breakthrough brought Aspect, Clauser, and Zeilinger the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics, “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science”. Quantum entanglement was mostly examined for states of photons and electrons until 2023, when ATLAS reported the observation of entanglement in the top quark-antiquark system.