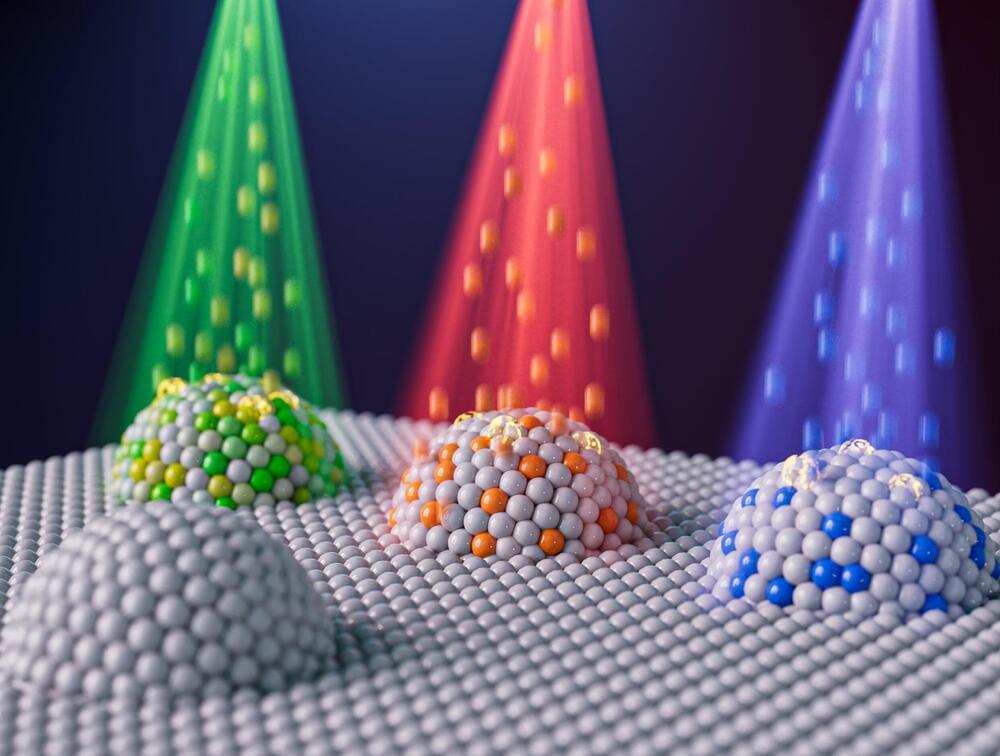

MIT researchers and colleagues have demonstrated a way to precisely control the size, composition, and other properties of nanoparticles key to the reactions involved in a variety of clean energy and environmental technologies. They did so by leveraging ion irradiation, a technique in which beams of charged particles bombard a material.

They went on to show that nanoparticles created this way have superior performance over their conventionally made counterparts.

“The materials we have worked on could advance several technologies, from fuel cells to generate CO2-free electricity to the production of clean hydrogen feedstocks for the chemical industry [through electrolysis cells],” says Bilge Yildiz, leader of the work and a professor in MIT’s Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering and Department of Materials Science and Engineering.