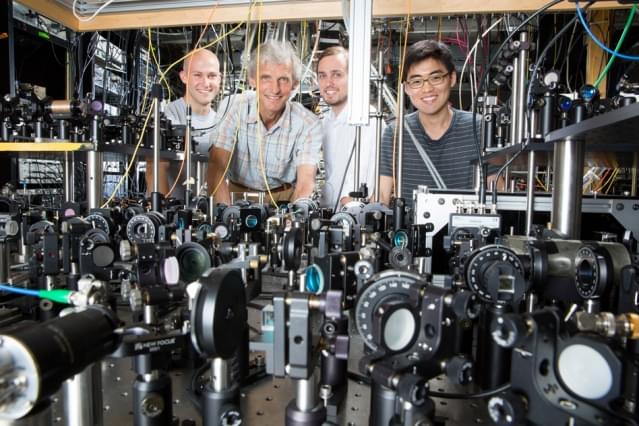

In a recent study, charged atoms, also known as ions, have been found to behave strangely during nuclear fusion reactions, in ways that scientists did not expect.

According to a paper published on November 14 in the journal Nature Physics, researchers at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory discovered that when deuterium and tritium ions, which are isotopes of hydrogen with one and two neutrons, respectively—are heated using lasers during laser-fusion experiments, there are more ions with higher energies than expected when a thermonuclear burn starts.

“The process of inertial confinement fusion (ICF) squeezes a small (1mm radius) capsule filled with a layer of frozen deuterium and tritium (isotopes of hydrogen) surrounding a volume of deuterium and tritium gas down to a radius of about 30 micrometers. In the process, these isotopes of hydrogen ionize and a plasma of electrons, deuterium and tritium nuclei [is the result],” Edward Hartouni, a physicist at NIF and a co-author of the paper, told Newsweek.