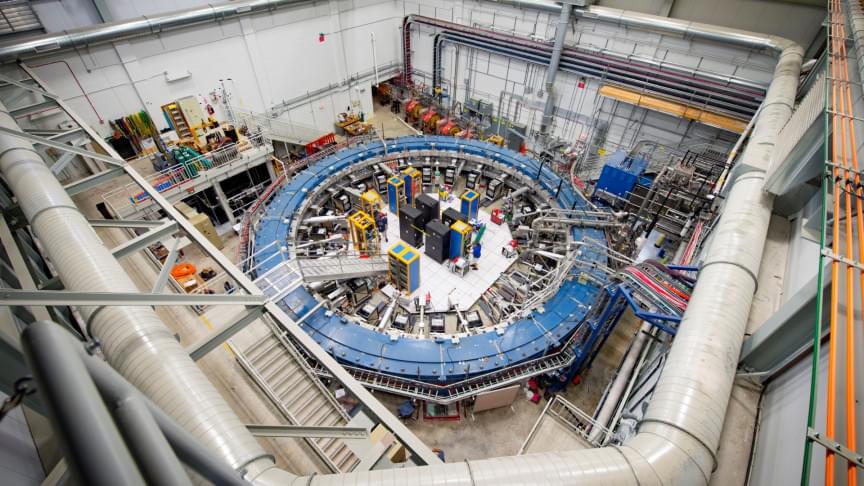

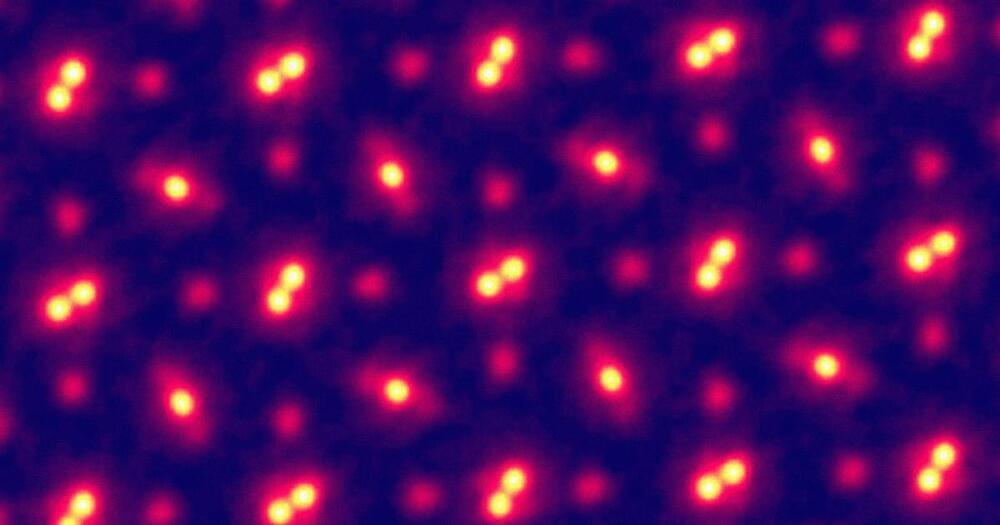

Physicists at EPFL, within a large European collaboration, have revised one of the fundamental laws that has been foundational to plasma and fusion research for over three decades, even governing the design of megaprojects like ITER. The update shows that we can actually safely use more hydrogen fuel in fusion reactors, and therefore obtain more energy than previously thought.

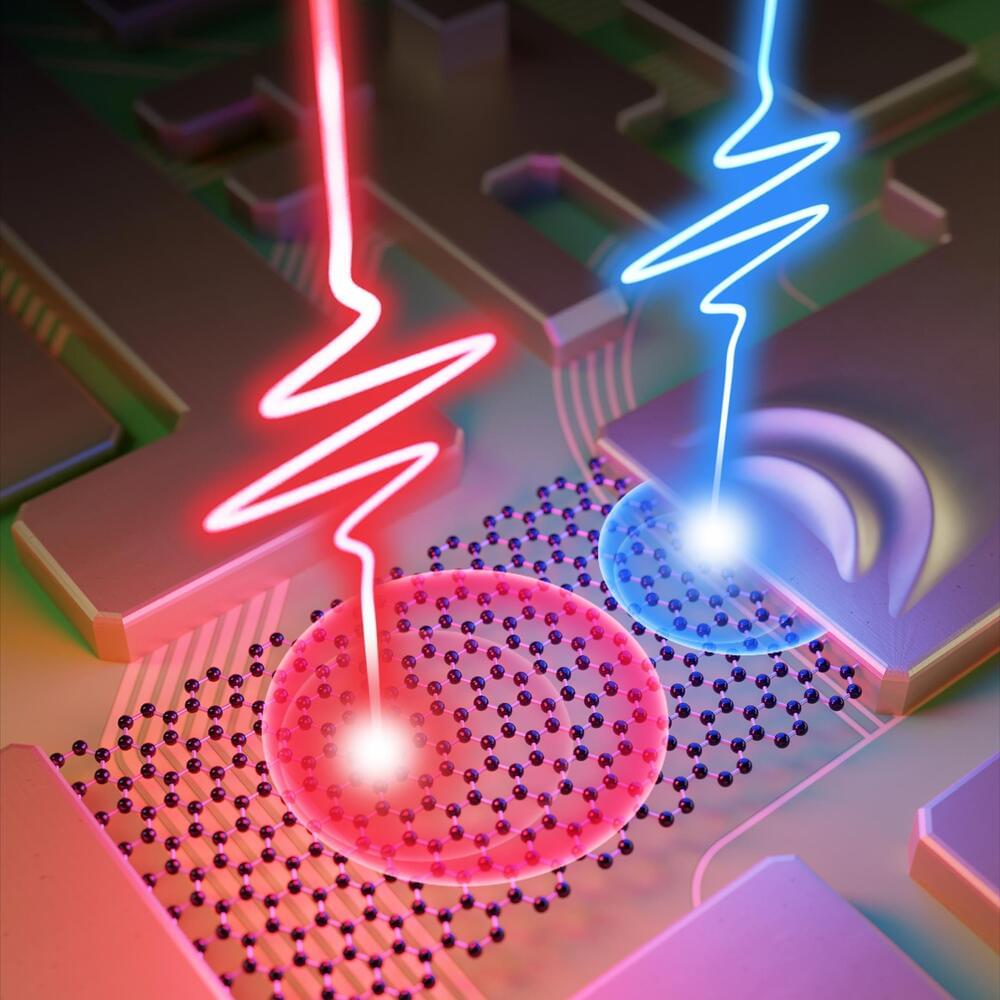

Fusion is one of the most promising sources of future energy. It involves two atomic nuclei combining into one, thereby releasing enormous amounts of energy. In fact, we experience fusion every day: the sun’s warmth comes from hydrogen nuclei fusing into heavier helium atoms.

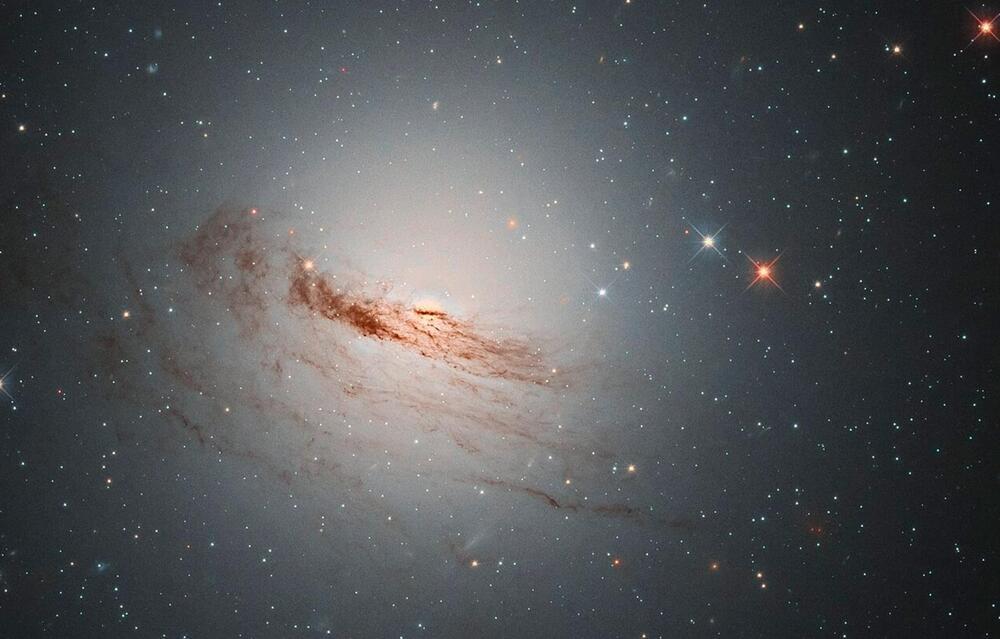

There is currently an international fusion research megaproject called ITER, which aims to replicate the fusion processes of the sun to create energy on the Earth. Its aim is the creation of high temperature plasma that provides the right environment for fusion to occur, producing energy.