A team of researchers affiliated with several institutions in the U.K. and one in Saudi Arabia has developed a way to produce jet fuel using carbon dioxide as a main ingredient. In their paper published in the journal Nature Communications, the group describes their process and its efficiency.

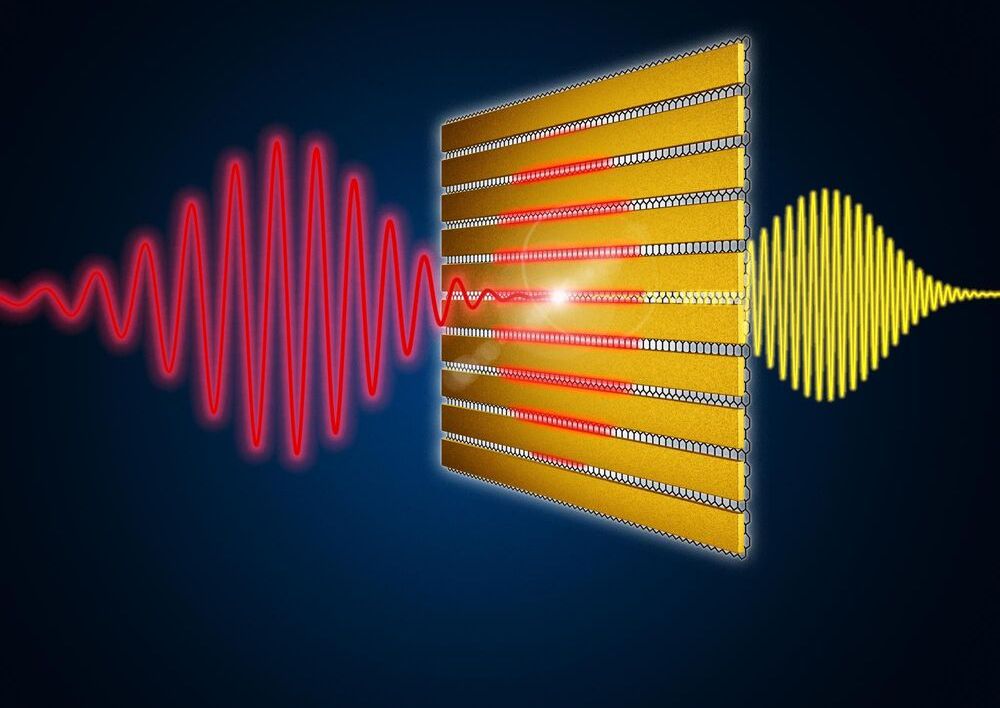

As scientists continue to look for ways to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere, they have increasingly focused on certain business sectors. One of those sectors is the aviation industry, which accounts for approximately 12% of transportation-related carbon dioxide emissions. Curbing carbon emissions in the aviation industry has proved to be challenging due to the difficulty of fitting heavy batteries inside of aircraft. In this new effort, the researchers have developed a chemical process that can be used to produce carbon-neutral jet fuel.

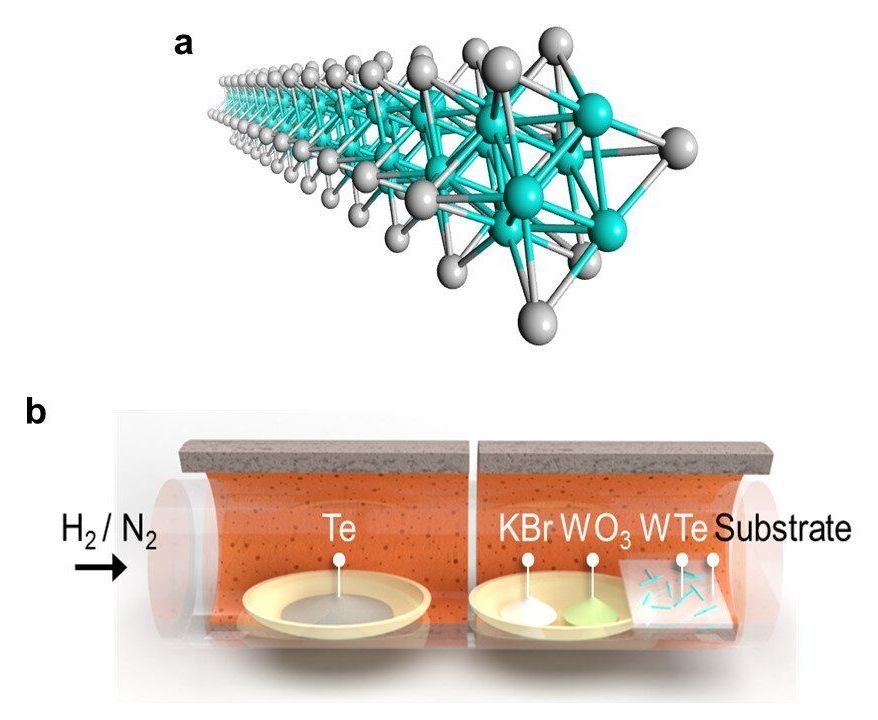

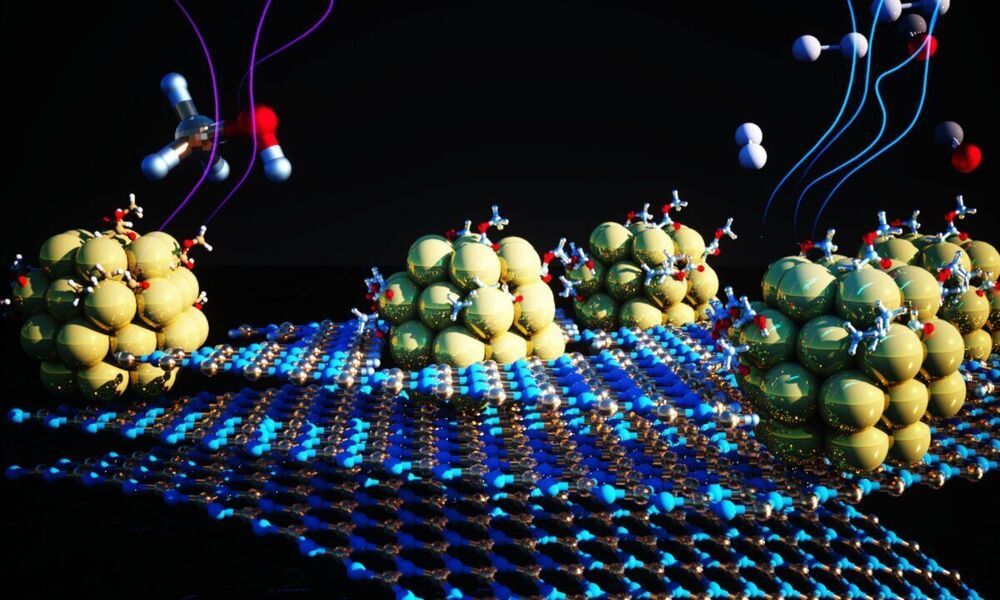

The researchers used a process called the organic combustion method to convert carbon dioxide in the air into jet fuel and other products. It involved using an iron catalyst (with added potassium and manganese) along with hydrogen, citric acid and carbon dioxide heated to 350 degrees C. The process forced the carbon atoms apart from the oxygen atoms in CO2 molecules, which then bonded with hydrogen atoms, producing the kind of hydrocarbon molecules that comprise liquid jet fuel. The process also resulted in the creation of water molecules and other products.