Error free qubits o.,o.

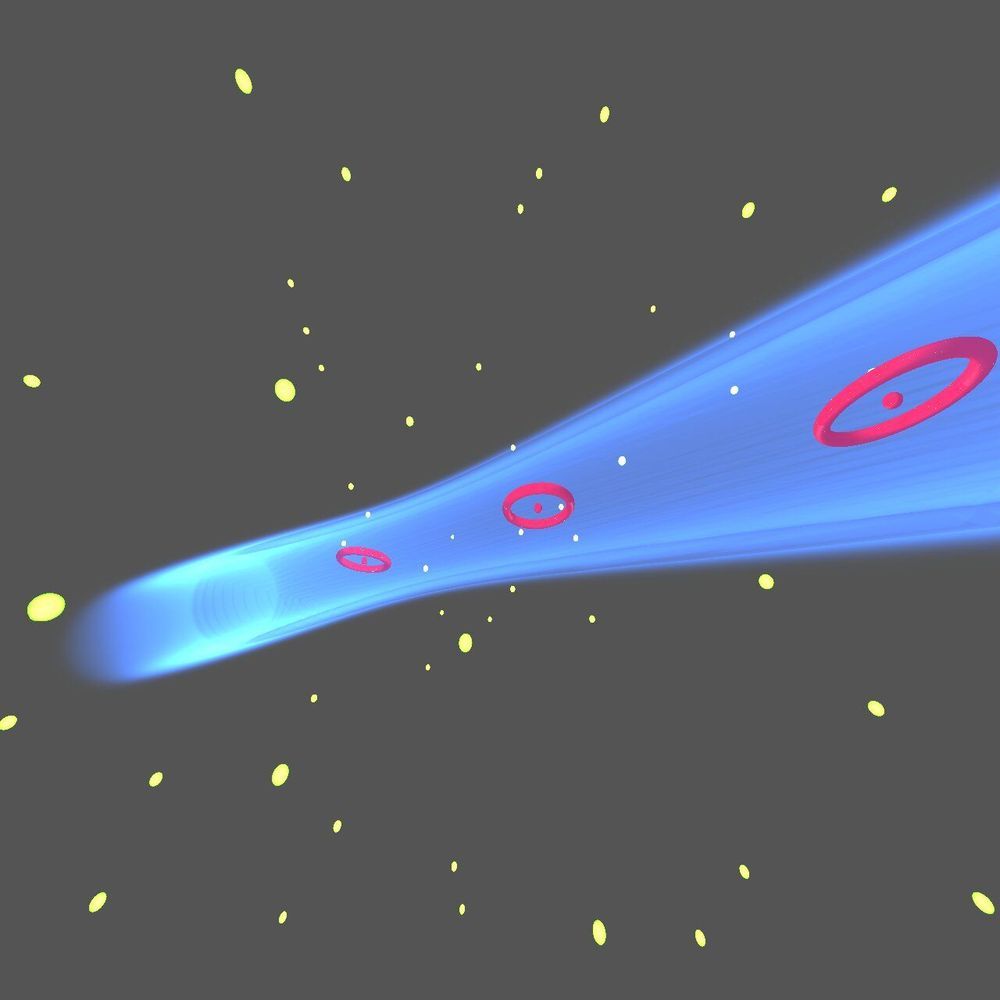

Physicists at MIT and elsewhere have observed evidence of Majorana fermions—particles that are theorized to also be their own antiparticle—on the surface of a common metal: gold. This is the first sighting of Majorana fermions on a platform that can potentially be scaled up. The results, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, are a major step toward isolating the particles as stable, error-proof qubits for quantum computing.

In particle physics, fermions are a class of elementary particles that includes electrons, protons, neutrons, and quarks, all of which make up the building blocks of matter. For the most part, these particles are considered Dirac fermions, after the English physicist Paul Dirac, who first predicted that all fermionic fundamental particles should have a counterpart, somewhere in the universe, in the form of an antiparticle—essentially, an identical twin of opposite charge.

In 1937, the Italian theoretical physicist Ettore Majorana extended Dirac’s theory, predicting that among fermions, there should be some particles, since named Majorana fermions, that are indistinguishable from their antiparticles. Mysteriously, the physicist disappeared during a ferry trip off the Italian coast just a year after making his prediction. Scientists have been looking for Majorana’s enigmatic particle ever since. It has been suggested, but not proven, that the neutrino may be a Majorana particle. On the other hand, theorists have predicted that Majorana fermions may also exist in solids under special conditions.