A high-precision experiment is hunting for a forbidden particle flip that could expose new physics hiding in plain sight.

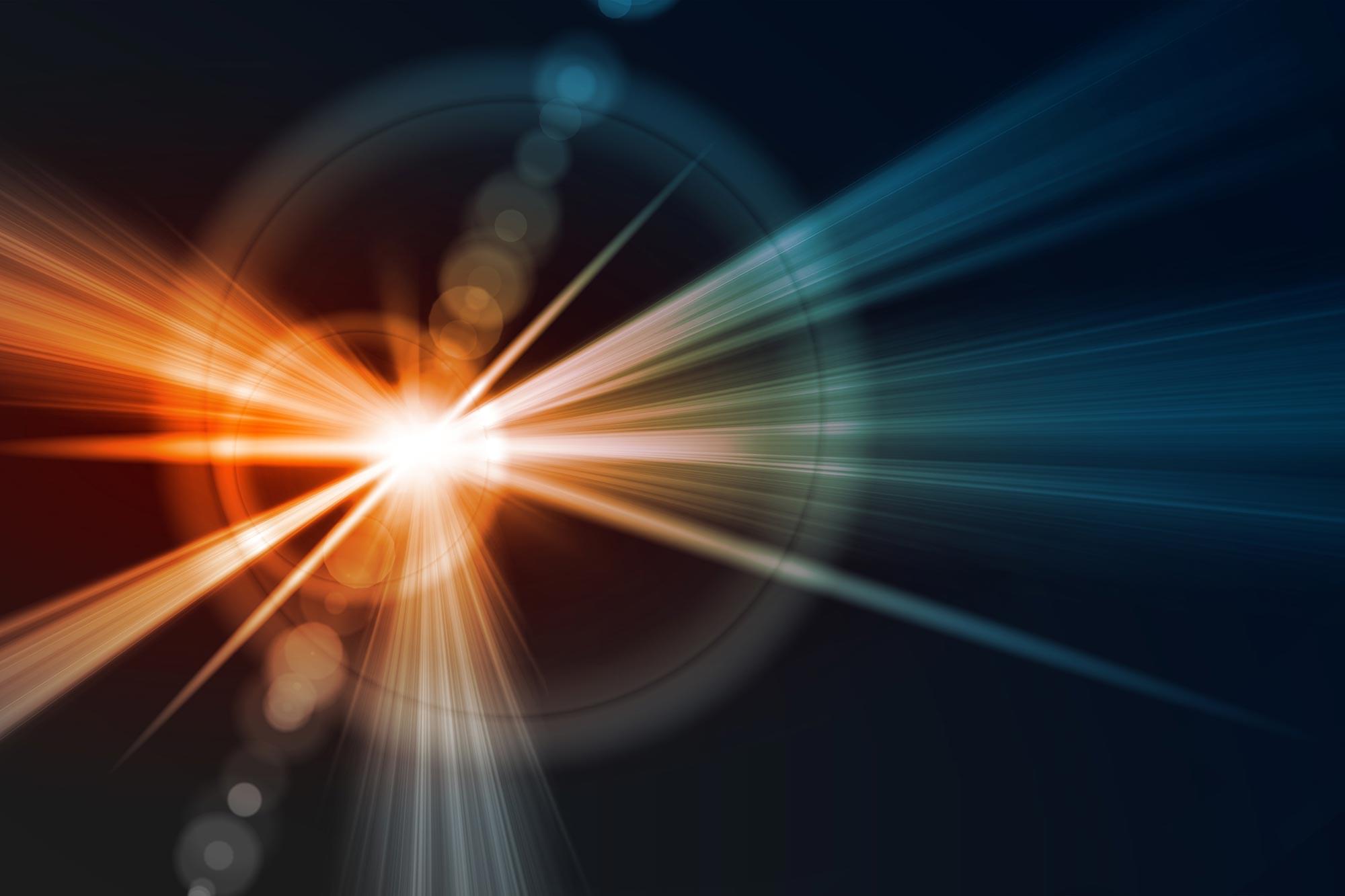

Through new experiments, researchers in Japan and Germany have recreated the chemical conditions found in the subsurface ocean of Saturn’s moon, Enceladus. Published in Icarus, the results show that these conditions can readily produce many of the organic compounds observed by the Cassini mission, strengthening evidence that the distant world could harbor the molecular building blocks of life.

Beneath its thick outer shell of ice, astronomers widely predict that Saturn’s sixth largest moon hosts an ocean of liquid water in its south polar region. The main evidence for this ocean is a water-rich plume which frequently erupts from fractures in Enceladus’ surface, leaving a trail of ice particles in its orbital paths which contributes to one of its host planet’s iconic rings.

Between 2004 and 2017, NASA’s Cassini probe passed through this E-ring and plume several times. Equipped with instruments including mass spectrometers and an ultraviolet imaging spectrograph, it detected a diverse array of organic compounds: from simple carbon dioxide to larger hydrocarbon chains, which on Earth are essential molecular precursors to complex biomolecules.

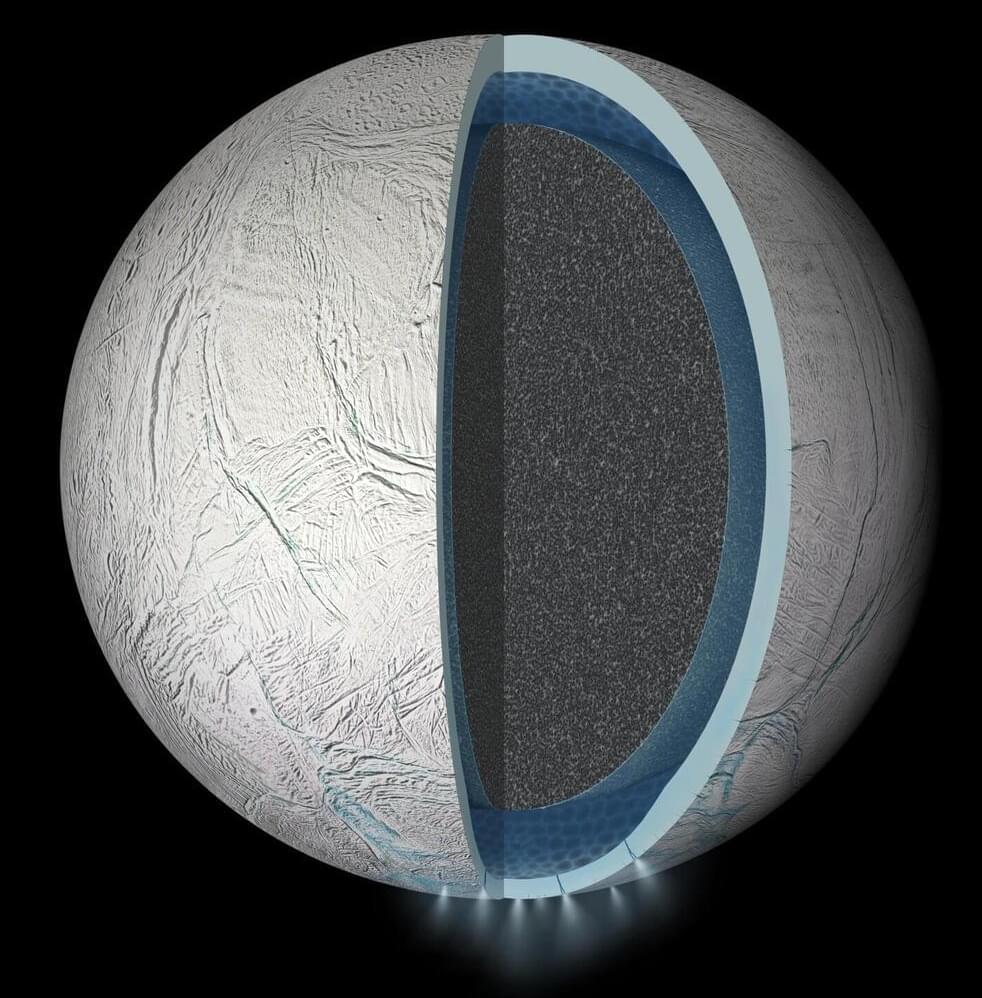

The handedness or chirality of a golf club, a baseball glove, or certain crystal lattices is plain to see: Their structures are such that one cannot be overlaid on its mirror image. Now Takayuki Ishitobi of the Japan Atomic Energy Agency and Kazumasa Hattori of Tokyo Metropolitan University have discovered that a crystal whose atomic structure is achiral can still host a chiral electronic state, which they dub purely electronic chirality (PEC) [1].

Four years ago, theorists found that the chirality of a crystalline structure can be quantified with a single number G0, which is given by the inner product of polar and axial vectors. The polar one is the electric dipole moment. The axial one is the electric toroidal dipole, which quantifies the geometric relationship between the electrons’ spin and orbital axes, and which is present in a few crystals with the requisite intricate arrangement of orbitals. Ishitobi and Hattori sought crystals whose atomic structures were achiral, but in which electronic interactions could induce an electric toroidal dipole and, therefore, a nonzero G0.

In some crystals, the conduction electrons occupy 2D planes. Ishitobi and Hattori realized that, if such a crystal also possesses atoms with electric quadrupole moments, the internal electric field could couple these quadrupoles to the electric toroidal dipole. A PEC would arise if the electric quadrupole has a specific arrangement and if the crystal has a certain lattice structure. From their calculations, the researchers determined that the intermetallic compound uranium rhodium stannide ticks all the boxes. They also found that the adoption of PEC by this material’s electrons could account for an unexplained phase transition at a temperature of 54 K.

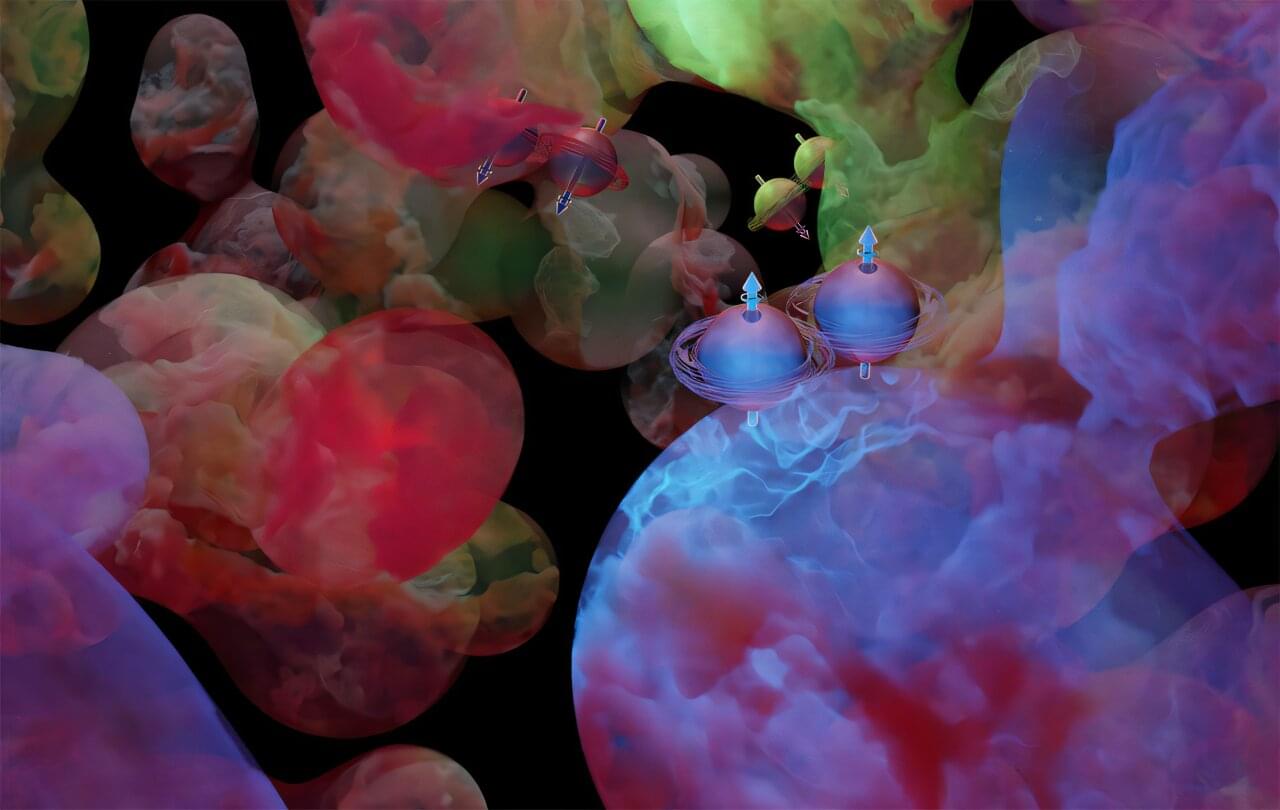

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have uncovered experimental evidence that particles of matter emerging from energetic subatomic smashups retain a key feature of virtual particles that exist only fleetingly in the quantum vacuum. The finding offers a new way to explore how the vacuum—once thought of as empty space—provides important ingredients needed to transform virtual “nothingness” into the matter that makes up our world.

The research, just published in Nature, was carried out by the STAR Collaboration at Brookhaven’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), a DOE Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research. The paper presents evidence of a significant correlation in particle spins—a built-in quantum property related to magnetism—among certain pairs of particles emerging from proton-proton collisions at RHIC.

The STAR scientists’ analysis directly links those correlations to the spin alignment of virtual quark-antiquark pairs generated in the quantum vacuum. In essence, the scientists say, RHIC’s collisions give those virtual particles the energetic boost they need to transform into the real particles detected by STAR.

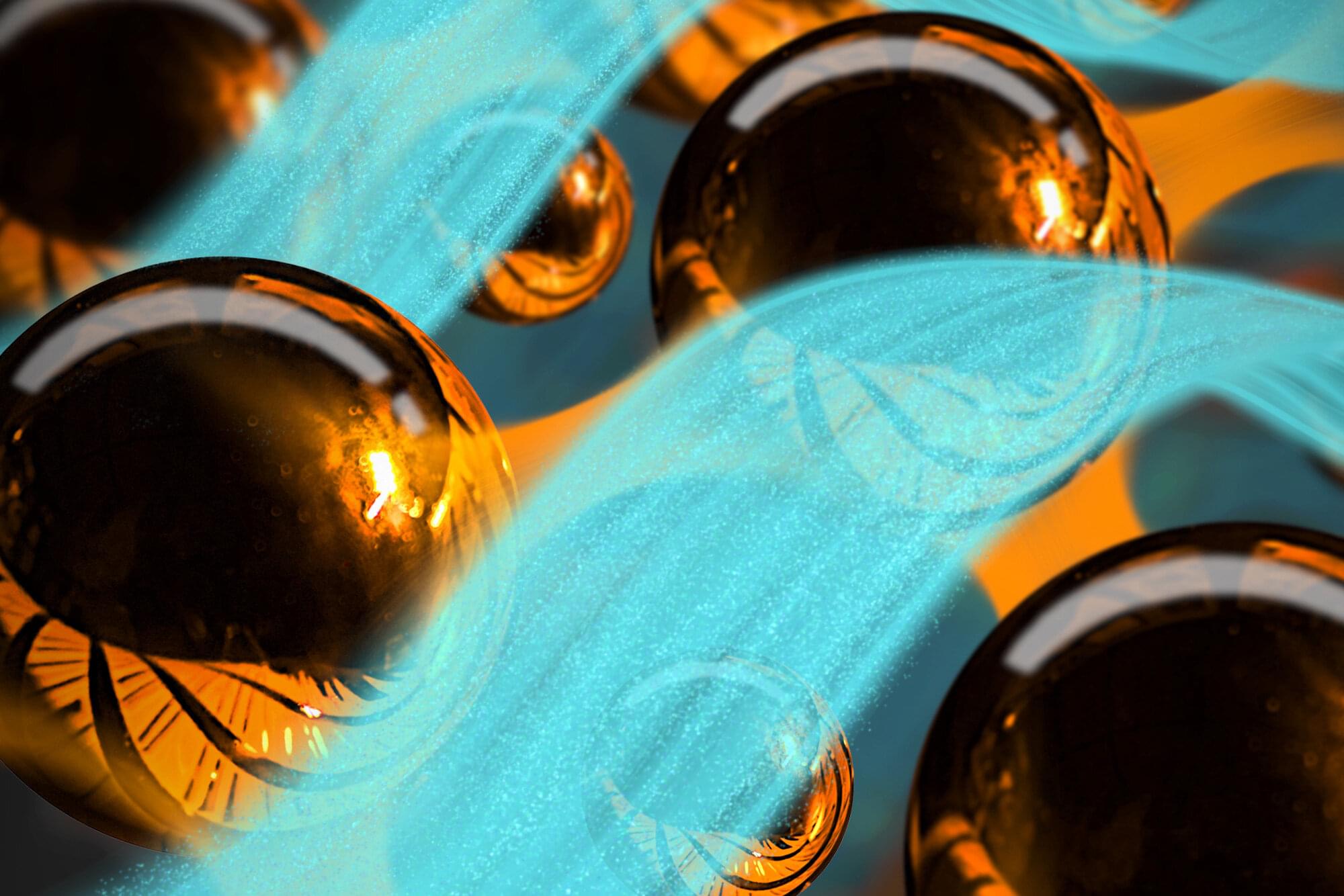

You can tell a lot about a material based on the type of light shining at it: Optical light illuminates a material’s surface, while X-rays reveal its internal structures and infrared captures a material’s radiating heat. Now, MIT physicists have used terahertz light to reveal inherent, quantum vibrations in a superconducting material, which have not been observable until now.

Terahertz light is a form of energy that lies between microwaves and infrared radiation on the electromagnetic spectrum. It oscillates over a trillion times per second—just the right pace to match how atoms and electrons naturally vibrate inside materials. Ideally, this makes terahertz light the perfect tool to probe these motions.

But while the frequency is right, the wavelength—the distance over which the wave repeats in space—is not. Terahertz waves have wavelengths hundreds of microns long. Because the smallest spot that any kind of light can be focused into is limited by its wavelength, terahertz beams cannot be tightly confined.

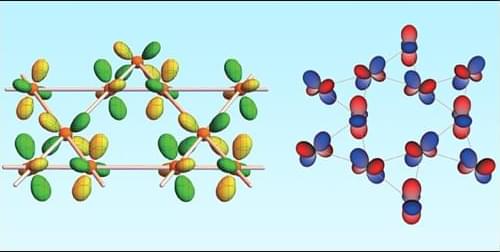

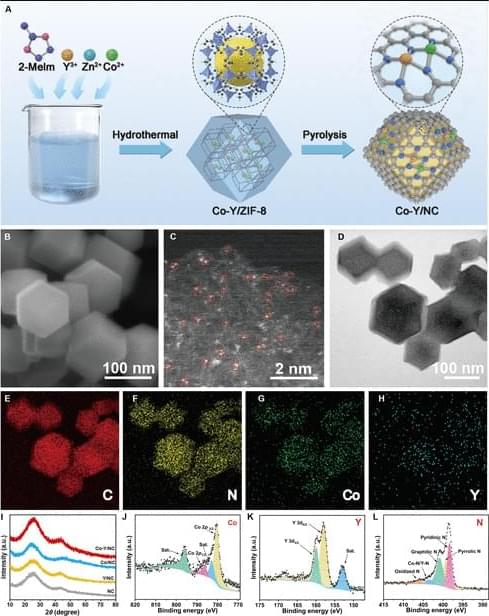

JUST PUBLISHED: JUST PUBLISHED: d–d/p Orbital Hybridization in Symmetry-Broken Co–Y Diatomic Sites Enables Efficient Na–S Battery.

Read the latest free, Open Access article from Energy Material Advances.

Despite advances of single-atom catalysts (SACs) in sodium–sulfur (Na–S) batteries, their symmetric coordination geometry (e.g., M–N4) fundamentally restricts orbital-level modulation of sulfur redox kinetics. Herein, we demonstrate that hetero-diatomic Co–Y sites with Co–N4–Y–N4 coordination on N-doped carbon (Co–Y/NC) break the M–N4 symmetry constraint through d–d orbital hybridization, which is confirmed by an implementation of advanced characterizations, including the high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy and x-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy. In practical operation, the Co–Y/NC@S cathode with 61% sulfur mass fraction delivers a superior capacity (1,109 mAh/g) at 0.2 A/g, outperforming that of Co or Y SAC and further setting a new benchmark of diatomic catalysts for Na–S battery systems.

Picture a spacecraft returning to Earth after a long journey. The vehicle slams into the planet’s atmosphere at roughly 17,000 miles per hour. A shockwave erupts. Molecules in the air are ripped apart, forming a plasma—a gas made of charged particles that can reach tens of thousands of degrees Fahrenheit, many times hotter than the surface of the sun.

The sight is spectacular to behold, but it’s also dangerous, said Hisham Ali, assistant professor in the Ann and H.J. Smead Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences.

The Columbia disaster is a tragic example. On Feb. 1, 2003, as the space shuttle reentered Earth’s atmosphere, plasma flooded into the vehicle through a defect in its shield of protective tiles. The shuttle disintegrated, and seven crewmembers, including CU Boulder alumna Kalpna Chawla, died.

In 2023, a subatomic particle called a neutrino crashed into Earth with such a high amount of energy that it should have been impossible. In fact, there are no known sources anywhere in the universe capable of producing such energy—100,000 times more than the highest-energy particle ever produced by the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator. However, a team of physicists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst recently hypothesized that something like this could happen when a special kind of black hole, called a “quasi-extremal primordial black hole,” explodes.

In new research published in Physical Review Letters, the team not only accounts for the otherwise impossible neutrino but shows that the elementary particle could reveal the fundamental nature of the universe.

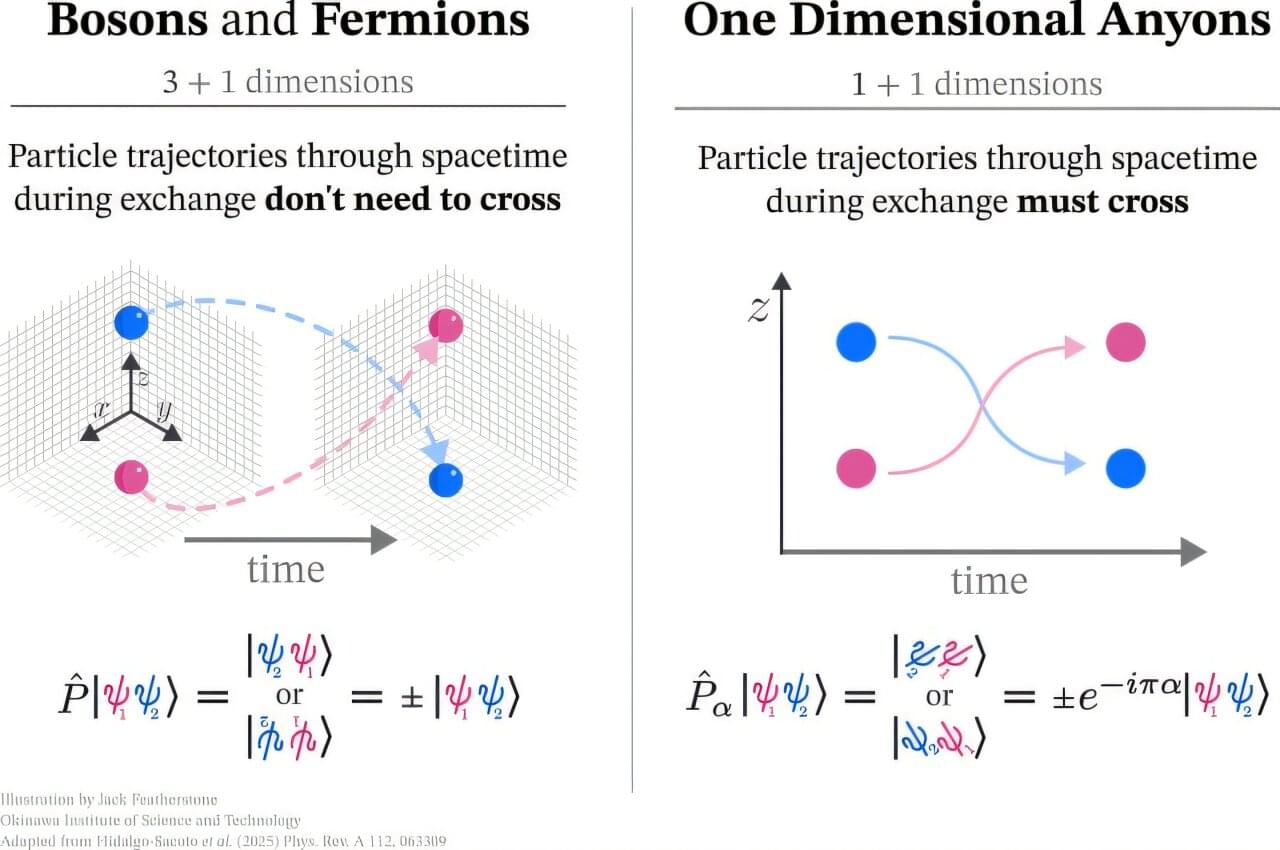

Physicists have long categorized every elementary particle in our three-dimensional universe as being either a boson or a fermion—the former category mostly capturing force carriers like photons, the latter including the building blocks of everyday matter like electrons, protons, or neutrons. But in lower dimensions of space, the neat categorization starts to break down.

Since the ’70s, a third class capturing anything in between a fermion and a boson, dubbed anyon, has been predicted to exist—and in 2020, these odd particles were observed experimentally at the interface of supercooled, strongly magnetized, one-atom thick (that is, two-dimensional) semiconductors. And now, in two joint papers published in Physical Review A, researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) and the University of Oklahoma have identified a one-dimensional system where such particles can exist and explored their theoretical properties.

Thanks to the recent developments in experimental control over single particles in ultracold atomic systems, these works also set the stage for investigating the fundamental physics of tunable anyons in realistic experimental settings. “Every particle in our universe seems to fit strictly into two categories: bosonic or fermionic. Why are there no others?” asks Professor Thomas Busch of the Quantum Systems Unit at OIST.

People have scanned the night sky for ages, but some of the Milky Way’s most important features cannot be seen with ordinary light. Dr. Jo-Anne Brown, PhD, is working to chart one of those hidden ingredients: the galaxy’s magnetic field, a vast structure that can influence how gas moves, where stars form, and how cosmic particles travel.

“Without a magnetic field, the galaxy would collapse in on itself due to gravity,” says Brown, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Calgary.

“We need to know what the magnetic field of the galaxy looks like now, so we can create accurate models that predict how it will evolve.”