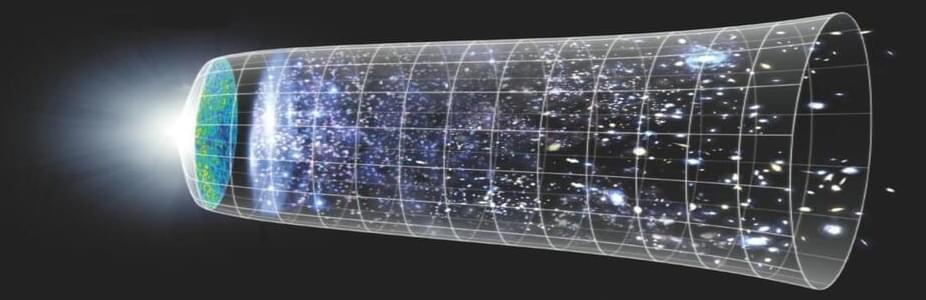

The Big Bang still happened a very long time ago, but it wasn’t the beginning we once supposed it to be.

Where did all this come from? In every direction we care to observe, we find stars, galaxies, clouds of gas and dust, tenuous plasmas, and radiation spanning the gamut of wavelengths: from radio to infrared to visible light to gamma rays. No matter where or how we look at the universe, it’s full of matter and energy absolutely everywhere and at all times. And yet, it’s only natural to assume that it all came from somewhere. If you want to know the answer to the biggest question of all — the question of our cosmic origins — you have to pose the question to the universe itself, and listen to what it tells you.

Today, the universe as we see it is expanding, rarifying (getting less dense), and cooling. Although it’s tempting to simply extrapolate forward in time, when things will be even larger, less dense, and cooler, the laws of physics allow us to extrapolate backward just as easily. Long ago, the universe was smaller, denser, and hotter. How far back can we take this extrapolation? Mathematically, it’s tempting to go as far as possible: all the way back to infinitesimal sizes and infinite densities and temperatures, or what we know as a singularity. This idea, of a singular beginning to space, time, and the universe, was long known as the Big Bang.