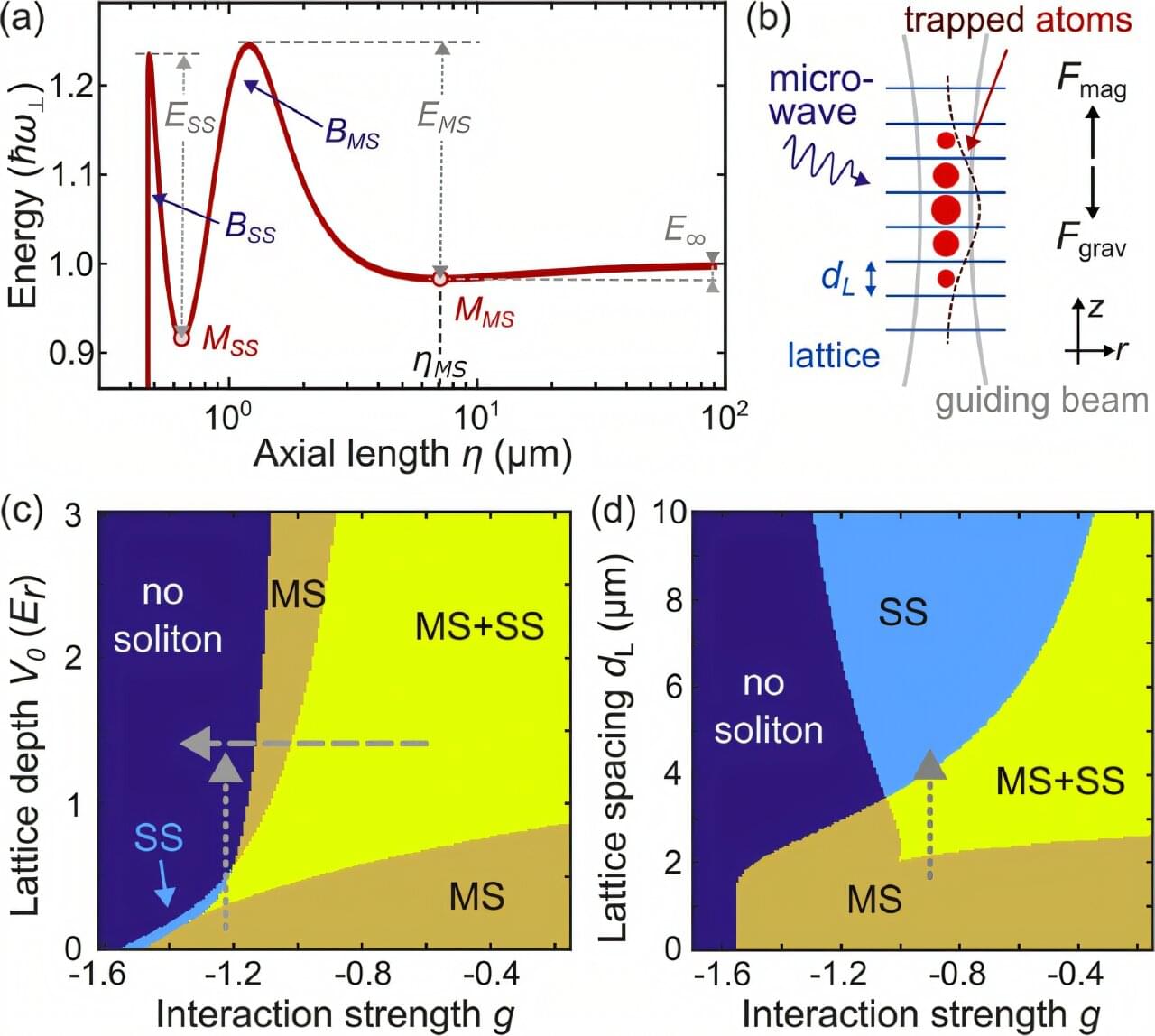

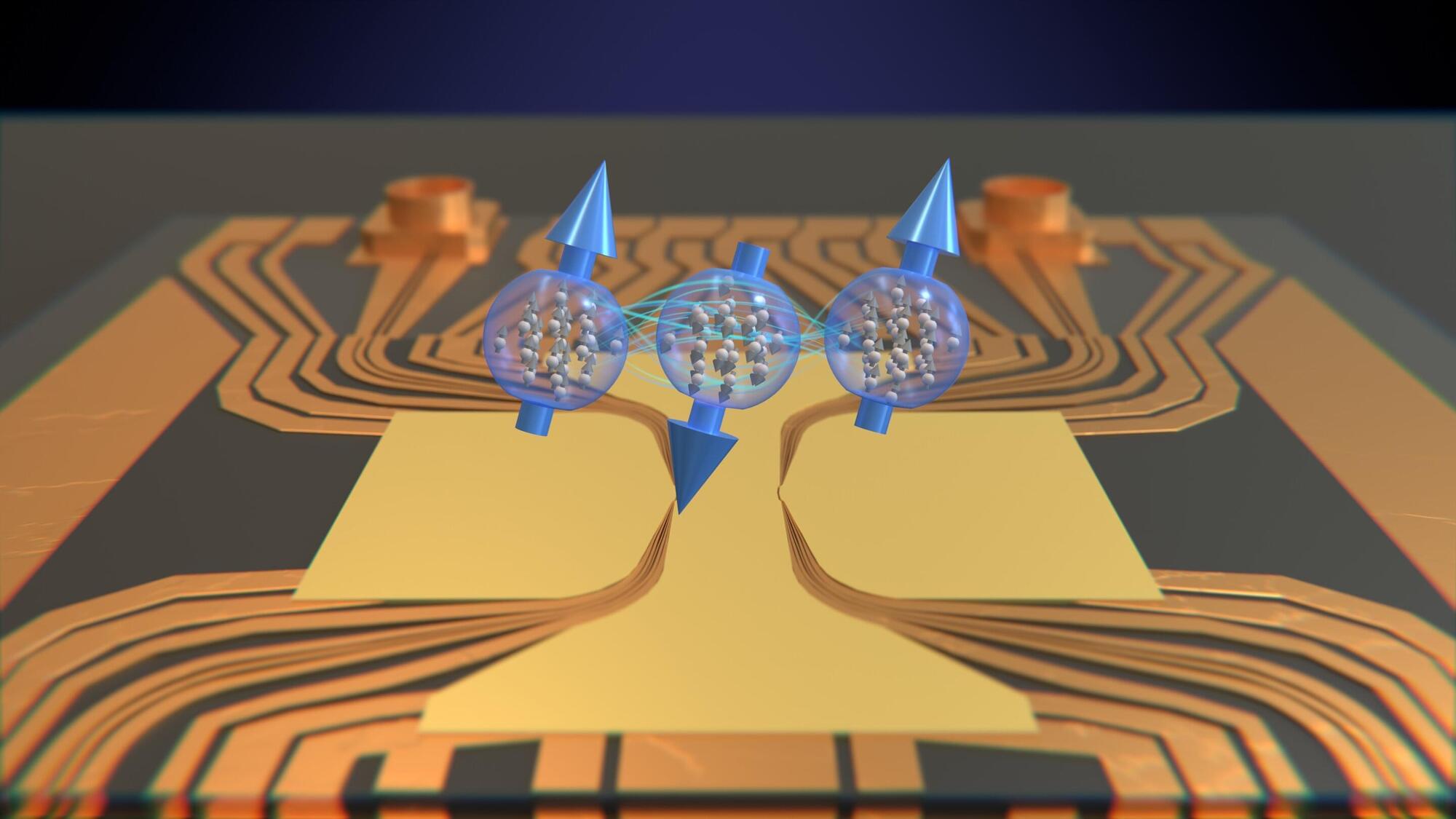

For the first time, physicists have generated and observed stable bright matter-wave solitons with attractive interactions within a grid of laser light.

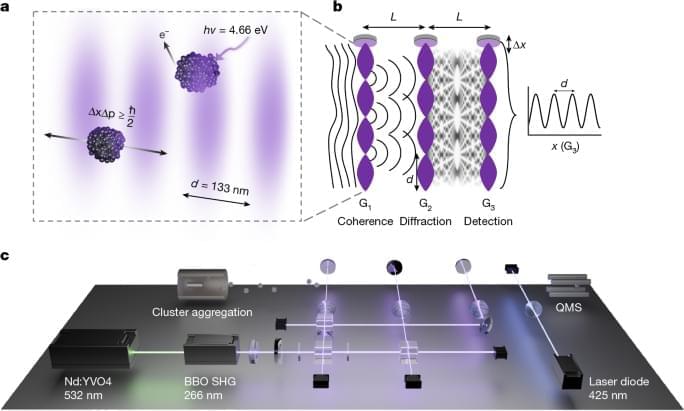

In the quantum world, atoms usually travel as waves that spread out, but solitons stay concentrated in one spot. They have been created before in open space, but this is the first time they have been stabilized inside a repeating laser structure using attractive forces. This development gives scientists a new way to hold and guide clusters of atoms, a key requirement for developing future quantum technologies.

The research is published in a paper in Physical Review Letters.