A new study published in Nature Communications delves into the manipulation of atomic-scale spin transitions using an external voltage, shedding light on the practical implementation of spin control at the nanoscale for quantum computing applications.

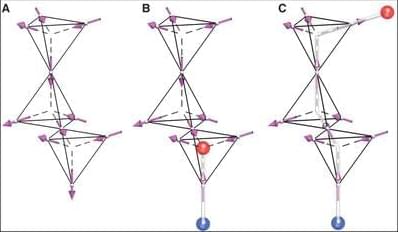

Spin transitions at the atomic scale involve changes in the orientation of an atom’s intrinsic angular momentum or spin. In the atomic context, spin transitions are typically associated with electron behavior.

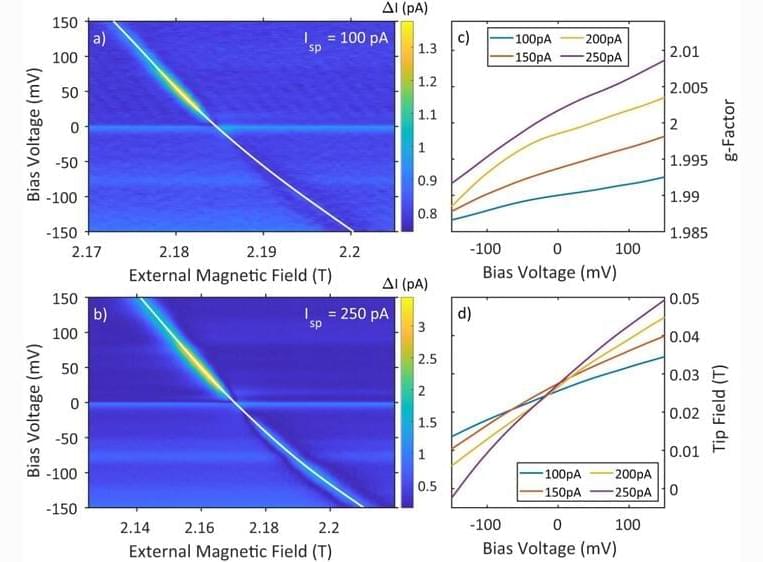

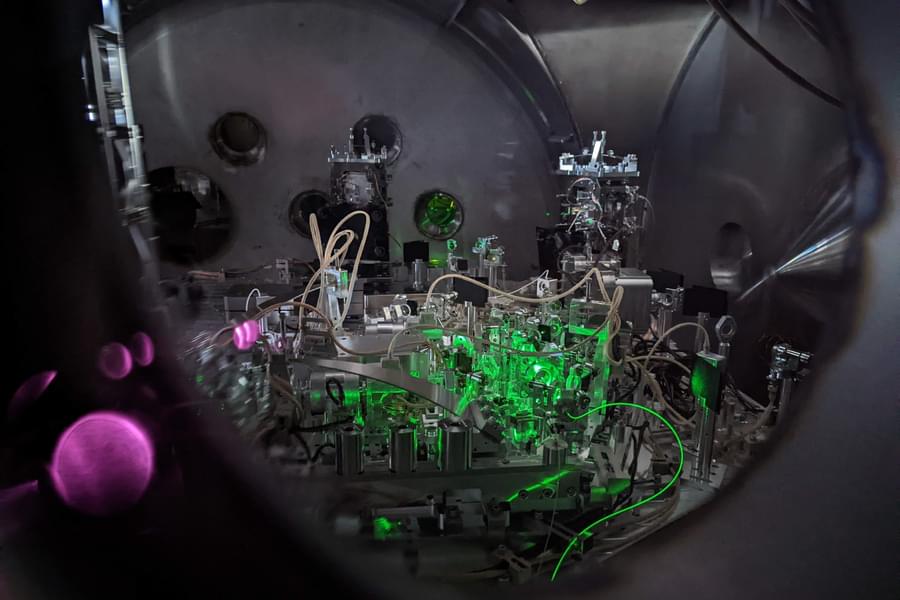

In this study, the researchers focused on using electric fields to control the spin transitions. The foundation of their research was serendipitous and driven by curiosity.