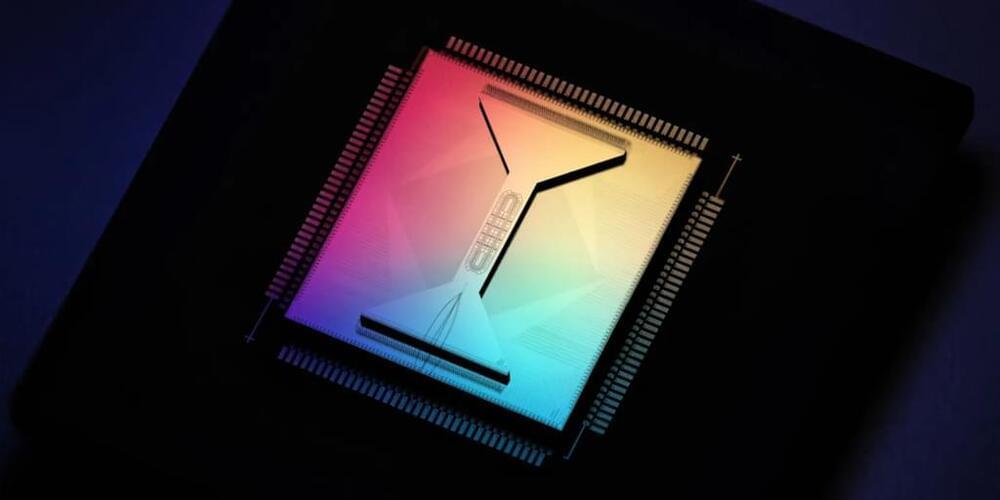

Moungi G. Bawendi, Louis E. Brus and Alexei I. Ekimov are awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2023 for the discovery and development of quantum dots. These tiny particles have unique properties and now spread their light from television screens and LED lamps. They catalyse chemical reactions and their clear light can illuminate tumour tissue for a surgeon.

“Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore,” is a classic quote from the film The Wizard of Oz. Twelve-year-old Dorothy faints onto her bed when her house is swept away by a powerful tornado, but when the house lands again and she steps outside the door, her dog Toto in her arms, everything has changed. Suddenly she is in a magical, technicolour world.

If an enchanted tornado were to sweep into our lives and shrink everything to nano dimensions, we would almost certainly be as astonished as Dorothy in the land of Oz. Our surroundings would be dazzlingly colourful and everything would change. Our gold earrings would suddenly glimmer in blue, while the gold ring on our finger would shine a ruby red. If we tried to fry something on the gas hob, the frying pan might melt. And our white walls – whose paint contains titanium dioxide – would start generating lots of reactive oxygen species.