The way light interacts with naturally occurring materials is well-understood in physics and materials science. But in recent decades, researchers have fabricated metamaterials that interact with light in new ways that go beyond the physical limits imposed on naturally occurring materials.

A metamaterial is composed of arrays of “meta-atoms,” which have been fabricated into desirable structures on the scale of about a hundred nanometers. The structure of arrays of meta-atoms facilitate precise light-matter interactions. However, the large size of meta-atoms relative to regular atoms, which are smaller than a nanometer, has limited the performance of metamaterials for practical applications.

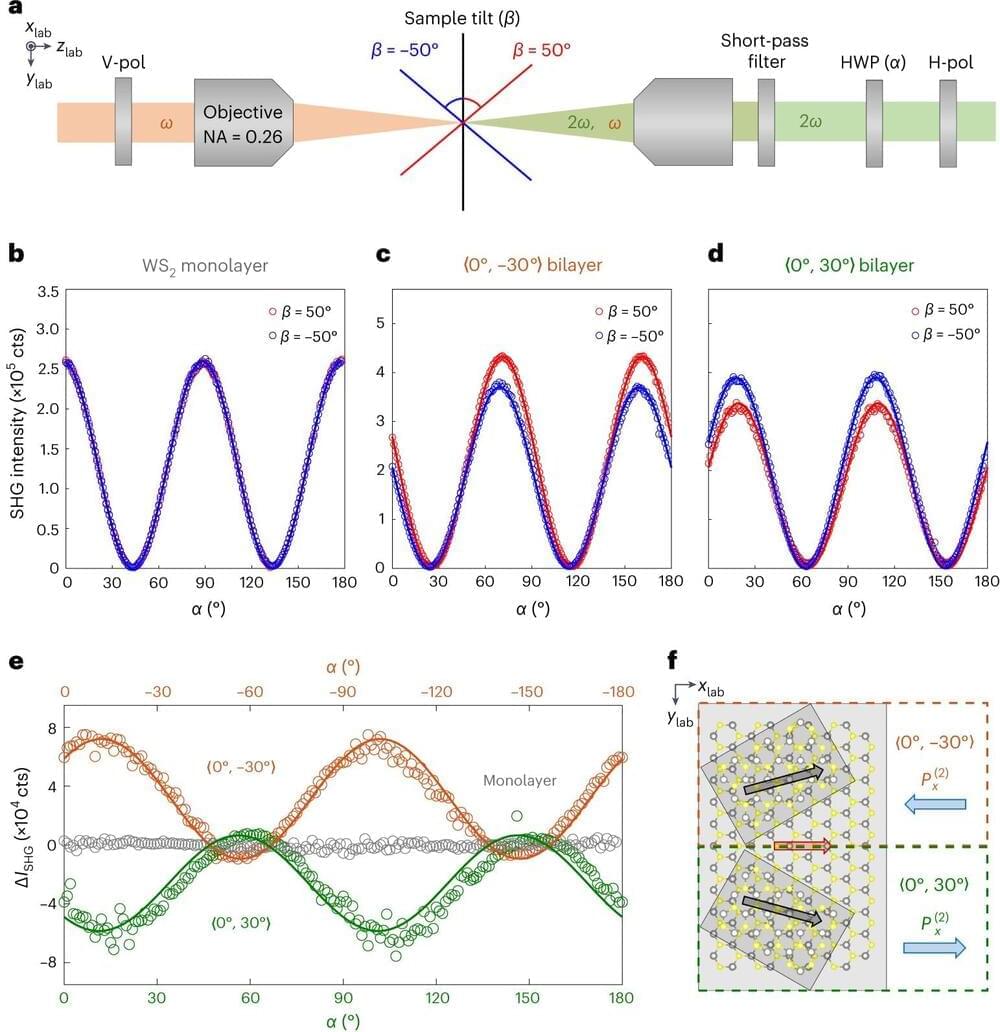

Now, a collaborative research team led by Bo Zhen of the University of Pennsylvania has unveiled a new approach that directly engineers atomic structures of material by stacking the two-dimensional arrays in spiral formations to tap into novel light-matter interaction. This approach enables metamaterials to overcome the current technical limitations and paves the way for next-generation lasers, imaging, and quantum technologies. Their findings were published in the journal Nature Photonics.