This year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognizes the development of quantum dots, particles whose size controls their color, making them useful for technologies such as displays.

“Using the new quantum ruler to study how the circular orbits vary with magnetic field, we hope to reveal the subtle magnetic properties of these moiré quantum materials”

Graphene, a single-atom-thick sheet of carbon, is renowned for its exceptional electrical conductivity and mechanical strength.

However, when two or more layers of graphene are stacked with a slight misalignment, they become moiré quantum matter, opening the door to a world of exotic possibilities. Depending on the angle of twist, these materials can generate magnetic fields, become superconductors with zero electrical resistance, or transform into perfect insulators.

To listen to more of John Wheeler’s stories, go to the playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLVV0r6CmEsFzVlqiUh95Q881umWUPjQbB

American physicist, John Wheeler (1911−2008), made seminal contributions to the theories of quantum gravity and nuclear fission, but is best known for coining the term ‘black holes’. A keen teacher and mentor, he was also a key figure in the Manhattan Project. [Listener: Ken Ford]

TRANSCRIPT: I knew the stories about Gödel being concerned always about his health. I knew from his friend Oscar Morgenstern how Gödel would never take a pills prescription from his doctor without getting out a big medical book and studying up on that pill himself to make sure that it was okay. But I didn’t realize how far his dreams went, because I had failed to resonate to a talk he gave in 1945 at the symposium held in honor of Einstein’s birthday. In that talk Gödel had described what he called a Rotating Universe, a universe where all the galaxies turn the same way, and where the geometry is such that you keep on going living your life and you come round and come back and can live it over again; ‘Closed Time-like Line’ was the magic phrase to describe it. So you didn’t have to worry about the pill because you come back and live your life all over again. Well, after I’d introduced the two I said “Professor Gödel, we’d like to know what the relation is between the great Heisenberg Principle of Uncertainty or Indeterminism; and your famous proof that every significant mathematical system contains theorems which cannot be proven, your theorem of Unprovable Propositions.” Well, he didn’t want to talk about that. It turned out that later that he had walked and talked enough with Einstein to dismiss quantum theory. He didn’t believe quantum[theory]. All he wanted to know is what we were going to say in our book about the rotating universe that he had described. Well actually, we weren’t saying anything. Well, this bothered him and he wanted to know what the evidence is today, at that moment, about whether galaxies do rotate in the same way. We said we hadn’t studied it. Well it turned out that he himself had taken out the great Hubble atlas of the galaxies and page after page had opened it up and looked at each galaxy, determined the direction of its axis. He made a statistics of these numbers and found there was no preferred direction of rotation, so they couldn’t all be rotating in the same way.

Physicists have used the famous particle smasher to investigate the strange phenomena of quantum entanglement at far higher energies than ever before.

By Alex Wilkins

In a schematic view, an engine uses a thermodynamic change to produce work. For example, when a gas is ignited, it expands and so pushes a piston. Now, researchers have been able to develop a similar kind of engine but instead of using the relationship between temperature, pressure, and volume, the new device uses quantum mechanics.

The quantum engine employs a gas that can turn from a fermion gas to a boson gas. Fermions and bosons are a way to divide all particles into two categories. Their difference comes from a property called spin, an intrinsic angular momentum. Fermions have a fractional value (1÷2, 3/2) while bosons have integer spin (0, 1, 2, …).

There is another difference that matters in the engine too: the Pauli exclusion principle. And this only applies to fermions.

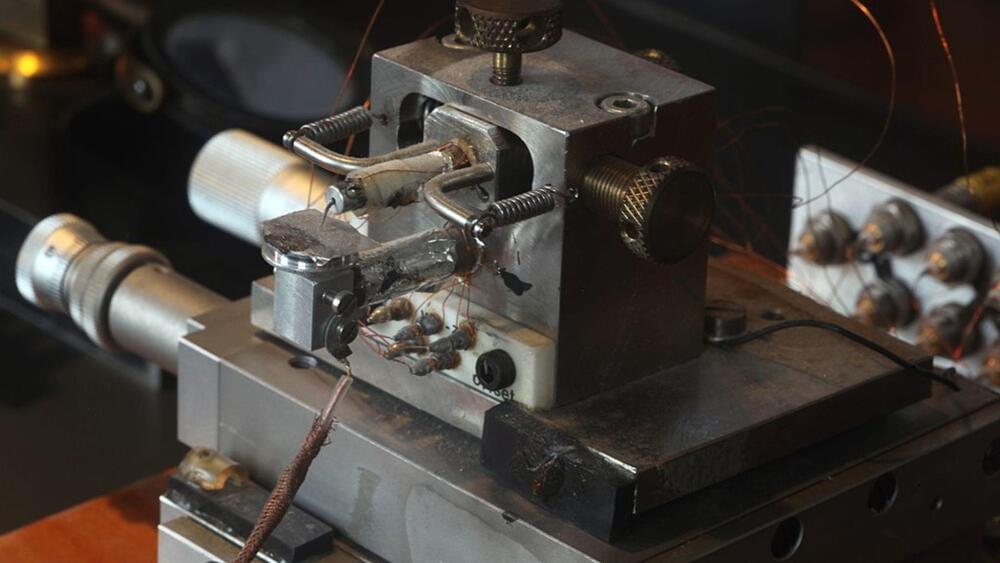

The method is still at its basic stage but multiple such microscopes could be pooled up to build a larger quantum computer.

Researchers at the IBS Center for Quantum Nanoscience (QNS) in Seoul, South Korea, have successfully demonstrated using a scanning tunneling microscope (STM) to perform quantum computation using electrons as qubits, a press release said.

Quantum computing is usually associated with terms such as atom traps or superconductors that aid in isolating quantum states or qubits that serve as a basic unit of information. In many ways, everything in nature is quantum and can be used to perform quantum computations as long as we can isolate its quantum states.

Missions to the Moon, missions to Mars, robotic explorers to the outer Solar System, a mission to the nearest star, and maybe even a spacecraft to catch up to interstellar objects passing through our system. If you think this sounds like a description of the coming age of space exploration, then you’d be correct! At this moment, there are multiple plans and proposals for missions that will send astronauts and/or probes to all of these destinations to conduct some of the most lucrative scientific research ever performed. Naturally, these mission profiles raise all kinds of challenges, not the least of which is propulsion.

Simply put, humanity is reaching the limits of what conventional (chemical) propulsion can do. To send missions to Mars and other deep space destinations, advanced propulsion technologies are required that offer high acceleration (delta-v), specific impulse (Isp), and fuel efficiency. In a recent paper, Leiden Professor Florian Neukart proposes how future missions could rely on a novel propulsion concept known as the Magnetic Fusion Plasma Drive (MFPD). This device combines aspects of different propulsion methods to create a system that offers high energy density and fuel efficiency significantly greater than conventional methods.

Florian Neukart is an Assistant Professor with the Leiden Institute of Advanced Computer Science (LIACS) at Leiden University and a Board Member of the Swiss quantum technology developer Terra Quantum AG. The preprint of his paper recently appeared online and is being reviewed for publication in Elsevier. According to Neukart, technologies that can surmount conventional chemical propulsion (CCP) are paramount in the present era of space exploration. In particular, these technologies must offer greater energy efficiency, thrust, and capability for long-duration missions.

In a new Physical Review Letters study, scientists have successfully presented a proof of concept to demonstrate a randomness-free test for quantum correlations and non-projective measurements, offering a groundbreaking alternative to traditional quantum tests that rely on random inputs.

“Quantum correlation” is a fundamental phenomenon in quantum mechanics and one that is central to quantum applications like communication, cryptography, computing, and information processing.

Bell’s inequality, or Bell’s theory, named after physicist John Stewart Bell, is the standard test used to determine the nature of correlation. However, one of the challenges with using Bell’s theorem is the requirement of seed randomness for selecting measurement settings.

The famous Copenhagen Interpretation favored by the founders of quantum mechanics is most definitely psi-epistemic. Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and others saw the state vector as being related to our interactions with the Universe. As Bohr said, “Physics is not about how the world is; it is about what we can say about the world.”

QBism is also definitively psi-epistemic, but it is not the Copenhagen Interpretation. Its epistemic focus grew organically from its founders’ work in quantum information science, which is arguably the most important development in quantum studies over the last 30 years. As physicists began thinking about quantum computers, they recognized that seeing the quantum in terms of information — an idea with strong epistemic grounding — provided new and powerful insights. By taking the information perspective seriously and asking, “Whose information?” the founders of QBism began a fundamentally new line of inquiry that, in the end, doesn’t require science fiction ideas like infinite parallel universes. That to me is one of its great strengths.

But, like all quantum interpretations, there is a price to be paid by QBism for its psi-epistemic perspective. The perfectly accessible, perfectly knowable Universe of classical physics is gone forever, no matter what interpretation you choose. We’ll dive into the price of QBism next time.

Quantum physicists have simulated super diffusion in quantum particles on a quantum computer, paving the way for deeper insights into condensed matter physics and materials science. This achievement, realized on a 27-qubit system programmed remotely from Dublin, emphasizes the potential of quantum computing in both commercial and fundamental physics inquiries.

Quantum physicists at Trinity, working alongside IBM Dublin, have successfully simulated super diffusion in a system of interacting quantum particles on a quantum computer.

This is the first step in doing highly challenging quantum transport calculations on quantum hardware and, as the hardware improves over time, such work promises to shed new light in condensed matter physics and materials science.