Even very slight environmental noise, such as microscopic vibrations or magnetic field fluctuations a hundred times smaller than Earth’s magnetic field, can be catastrophic for quantum computing experiments with trapped ions.

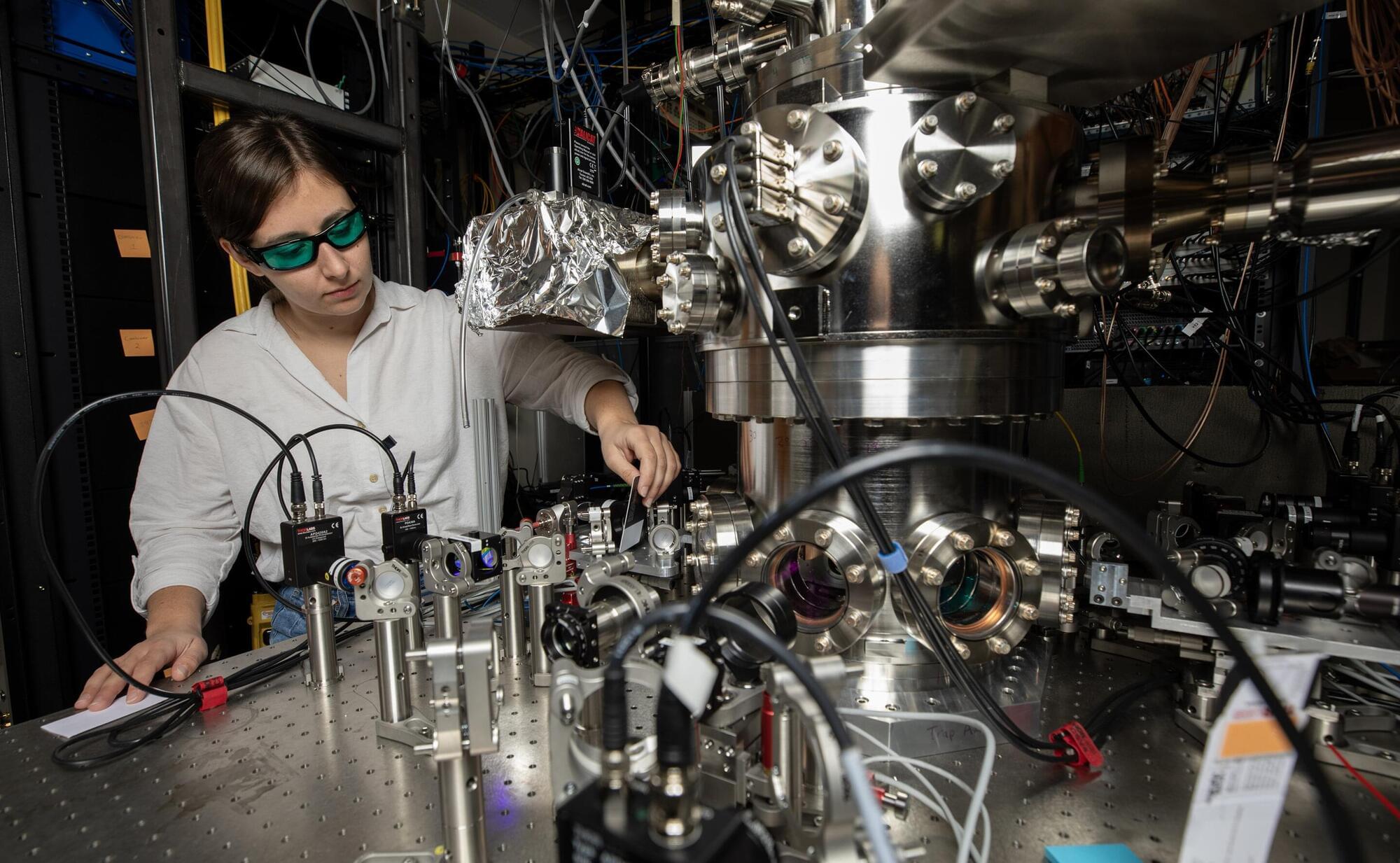

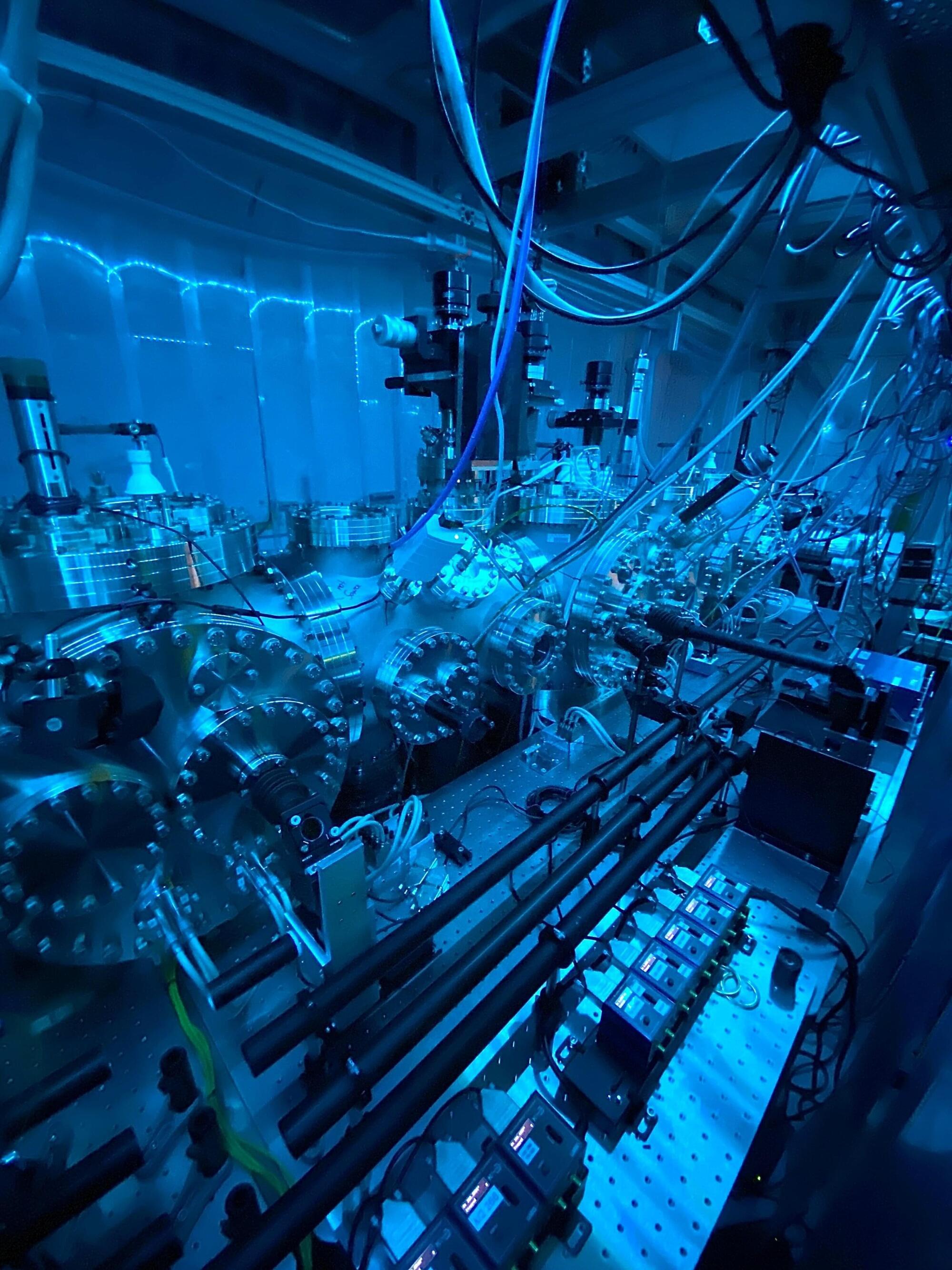

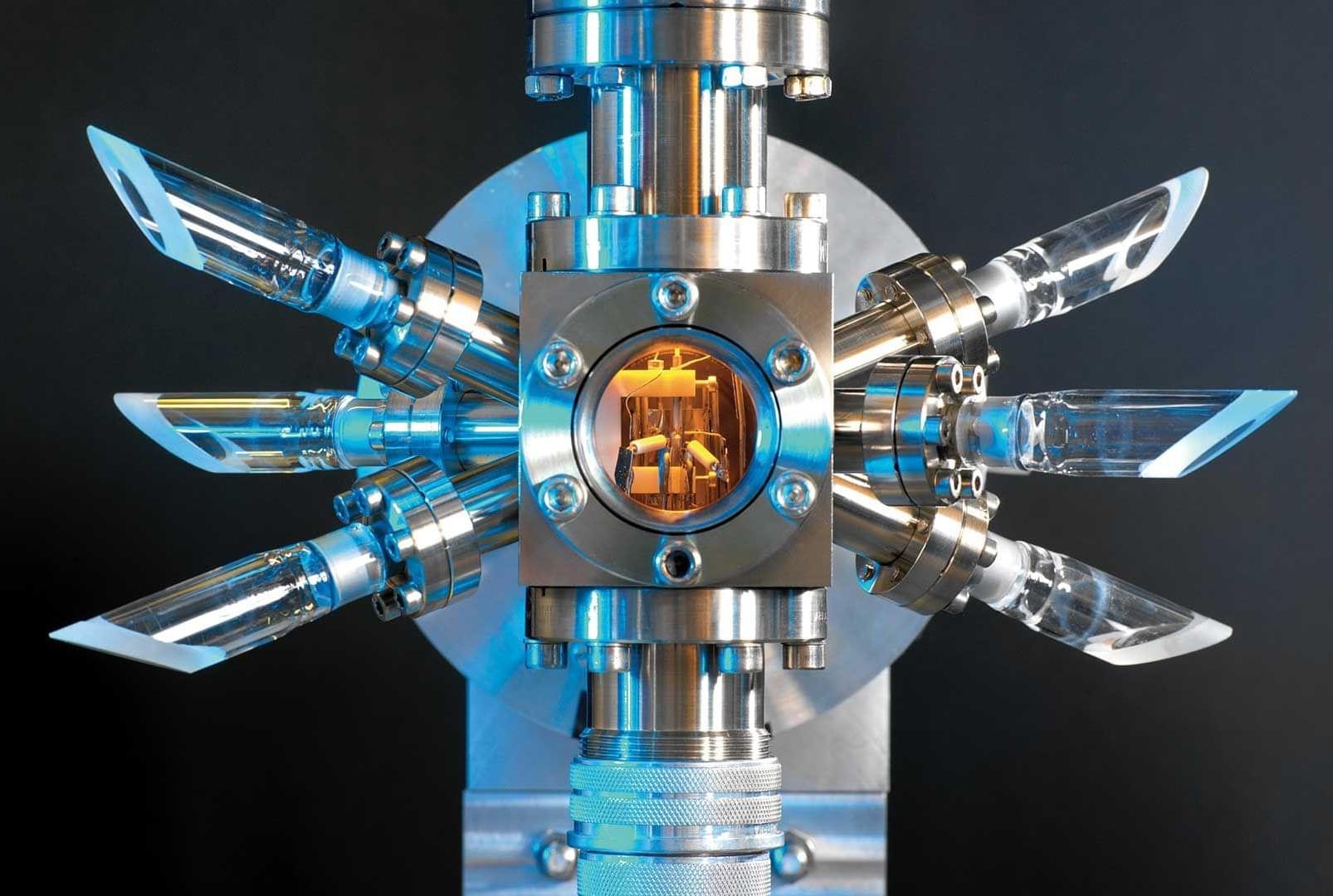

To address that challenge, researchers at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) have developed an improved cryogenic vacuum chamber that helps reduce some common noise sources by isolating ions from vibrations and shielding them from magnetic field fluctuations. The new chamber also incorporates an improved imaging system and a radio frequency (RF) coil that can be used to drive ion transitions from within the chamber.

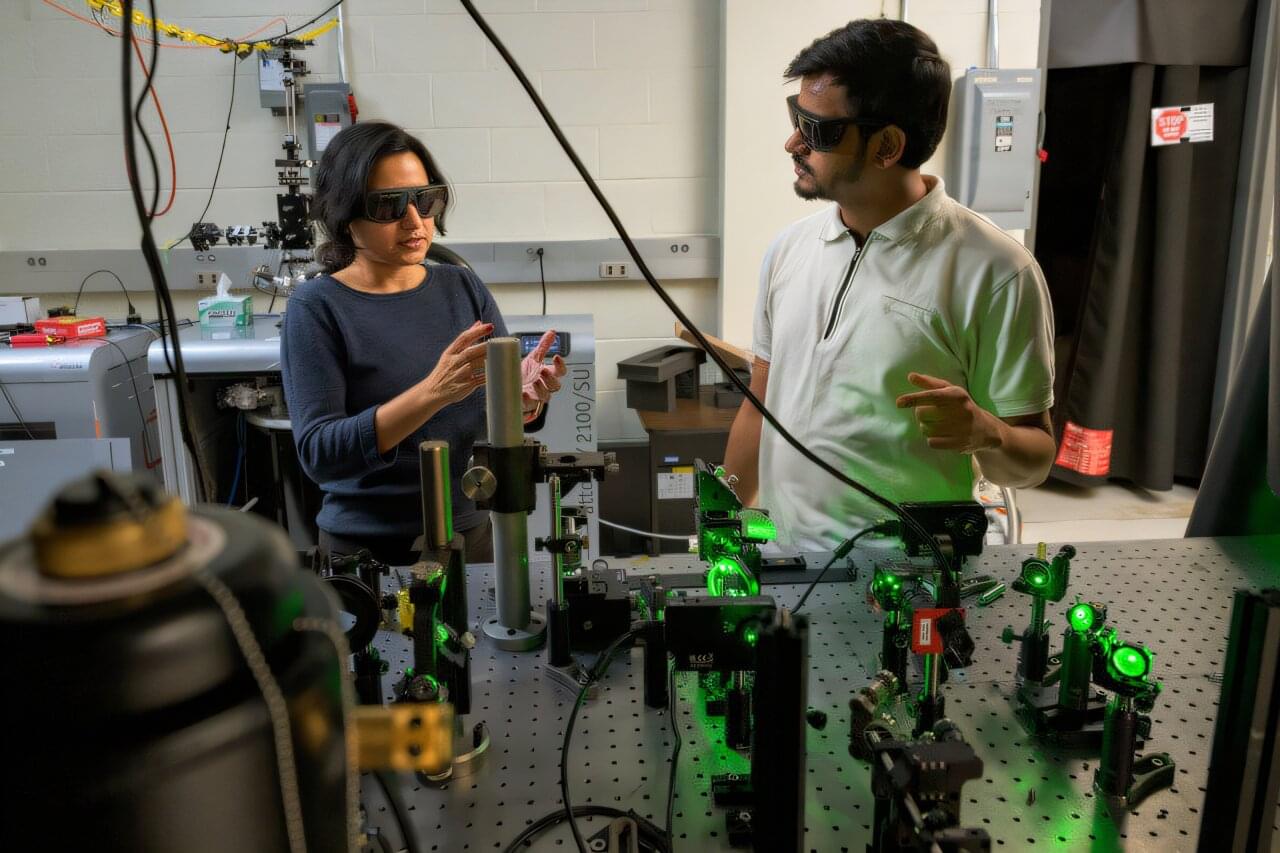

“There’s a lot of excitement around quantum computing today, and trapped ions are just one of the research platforms available, each with their own benefits and drawbacks,” explained Darian Hartsell, a GTRI research scientist who leads the project. “We are trying to mitigate multiple sources of noise in this chamber and make other improvements with one robust new design.”