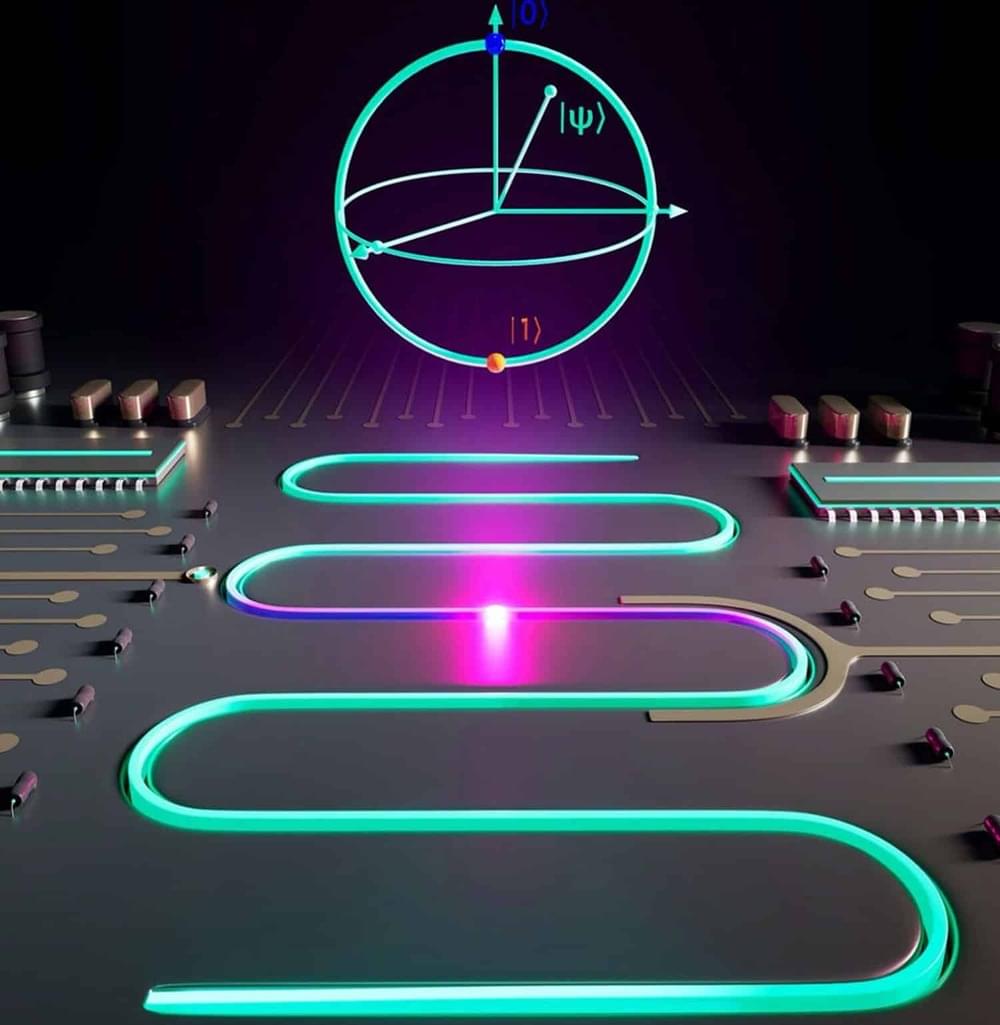

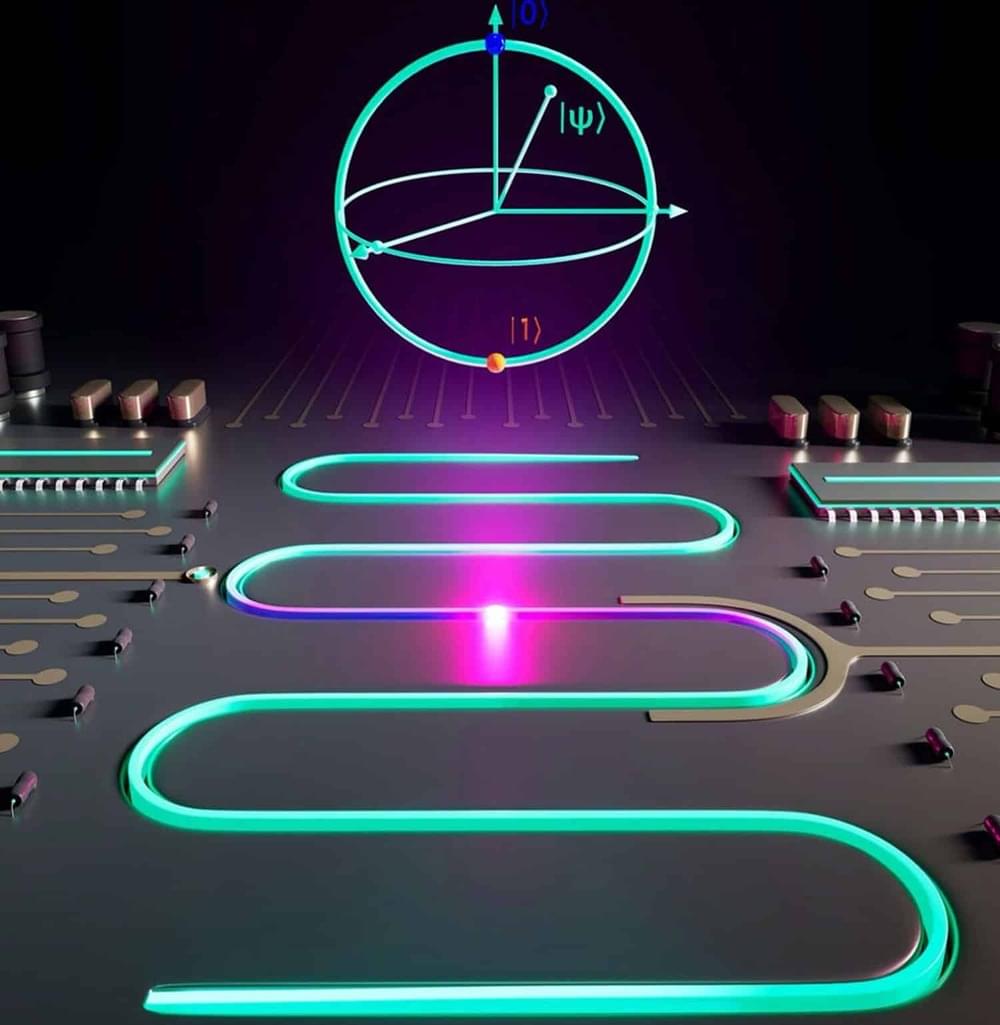

A new qubit to boost quantum computers for useful applications.

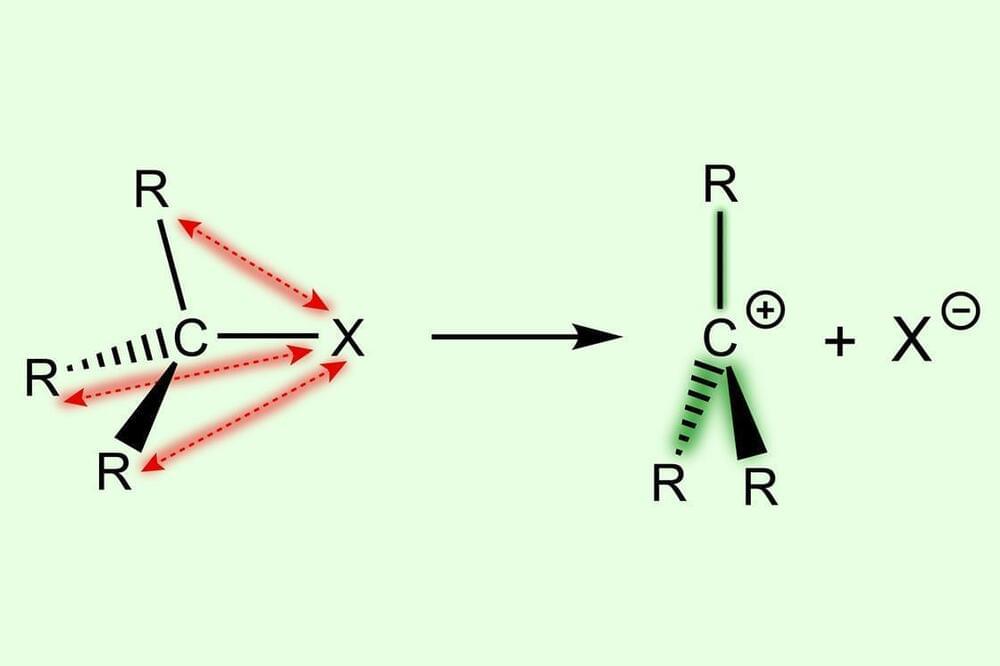

It is easier to form more substituted carbocations because of destabilisation in the parent substrate, rather than stabilisation in the reactive intermediate, new research shows.1

Many organic transformations involve carbocations as reactive intermediates. These are usually formed via a heterolytic C–X bond dissociation to give a carbocation C+ and an anion X-. Current understanding is that the bond dissociation energy decreases with increased methyl substitution because of the stabilising effect of the methyl groups, as well as relief due to steric repulsion: going from substrate to carbocation gives the substituents proportionally more room in a more substituted system. However, a team in the Netherlands, led by Matthias Bickelhaupt at VU Amsterdam, has investigated this from a different angle.

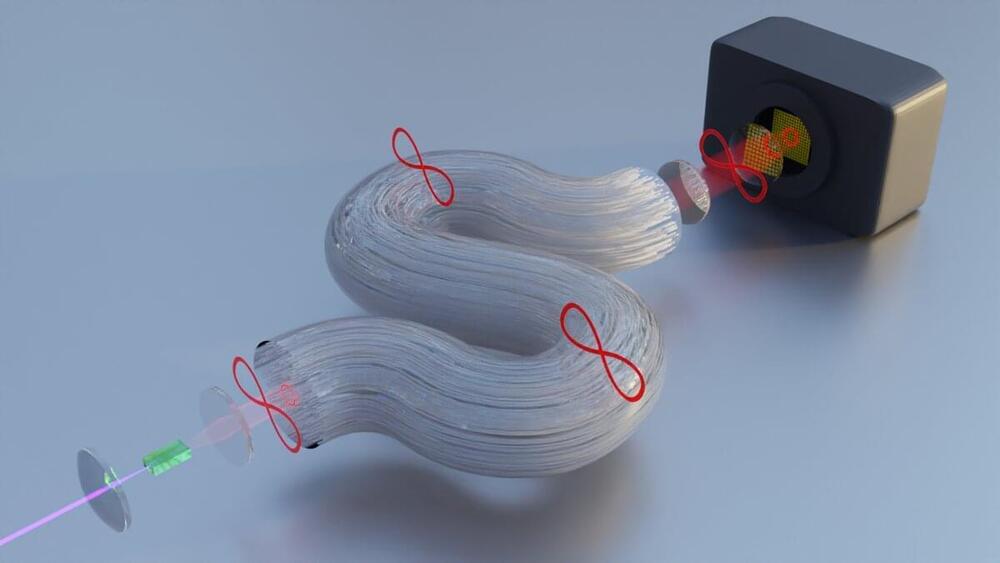

Invented in 1970 by Corning Incorporated, low-loss optical fiber became the best means to efficiently transport information from one place to another over long distances without loss of information. The most common way of data transmission nowadays is through conventional optical fibers—one single core channel transmits the information. However, with the exponential increase of data generation, these systems are reaching information-carrying capacity limits.

Thus, research now focuses on finding new ways to utilize the full potential of fibers by examining their inner structure and applying new approaches to signal generation and transmission. Moreover, applications in quantum technology are enabled by extending this research from classical to quantum light.

In the late 50s, the physicist Philip W. Anderson (who also made important contributions to particle physics and superconductivity) predicted what is now called Anderson localization. For this discovery, he received the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physics. Anderson showed theoretically under which conditions an electron in a disordered system can either move freely through the system as a whole, or be tied to a specific position as a “localized electron.” This disordered system can for example be a semiconductor with impurities.

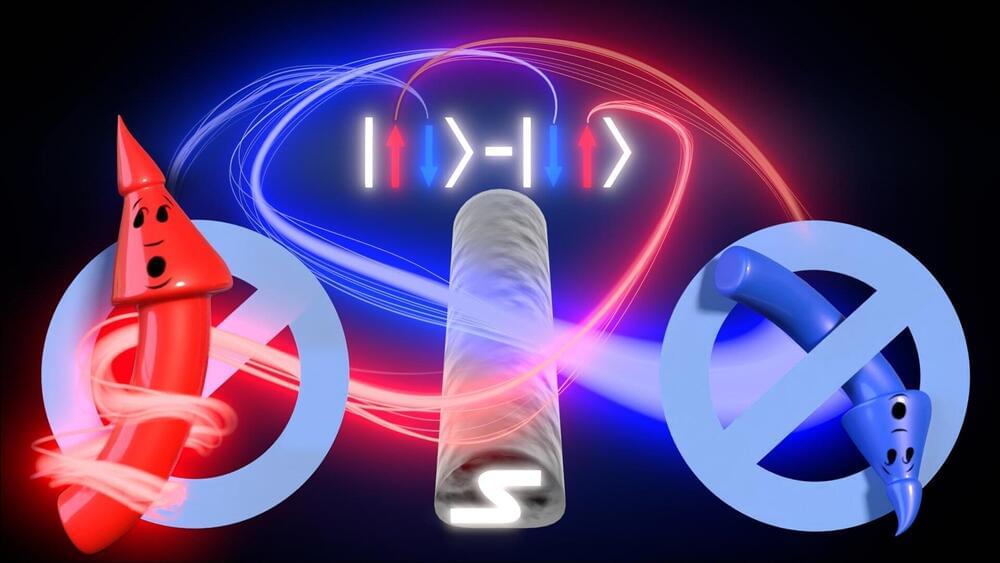

Physicists at the University of Basel have experimentally demonstrated for the first time that there is a negative correlation between the two spins of an entangled pair of electrons from a superconductor. For their study, the researchers used spin filters made of nanomagnets and quantum dots, as they report in the scientific journal Nature.

The entanglement between two particles is among those phenomena in quantum physics that are hard to reconcile with everyday experiences. If entangled, certain properties of the two particles are closely linked, even when far apart. Albert Einstein described entanglement as a “spooky action at a distance.” Research on entanglement between light particles (photons) was awarded this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics.

Two electrons can be entangled as well—for example in their spins. In a superconductor, the electrons form so-called Cooper pairs responsible for the lossless electrical currents and in which the individual spins are entangled.

Deep Learning AI Specialization: https://imp.i384100.net/GET-STARTED

AI News Timestamps:

0:00 New AI Robot Dog Beats Human Soccer Skills.

2:34 Breakthrough Humanoid Robotics & AI Tech.

5:21 Google AI Makes HD Video From Text.

8:41 New OpenAI DALL-E Robotics.

11:31 Elon Musk Reveals Tesla Optimus AI Robot.

16:49 Machine Learning Driven Exoskeleton.

19:33 Google AI Makes Video Game Objects From Text.

22:12 Breakthrough Tesla AI Supercomputer.

25:32 Underwater Drone Humanoid Robot.

29:19 Breakthrough Google AI Edits Images With Text.

31:43 New Deep Learning Tech With Light waves.

34:50 Nvidia General Robot Manipulation AI

36:31 Quantum Computer Breakthrough.

38:00 In-Vitro Neural Network Plays Video Games.

39:56 Google DeepMind AI Discovers New Matrices Algorithms.

45:07 New Meta Text To Video AI

48:00 Bionic Tech Feels In Virtual Reality.

53:06 Quantum Physics AI

56:40 Soft Robotics Gripper Learns.

58:13 New Google NLP Powered Robotics.

59:48 Ionic Chips For AI Neural Networks.

1:02:43 Machine Learning Interprets Brain Waves & Reads Mind.

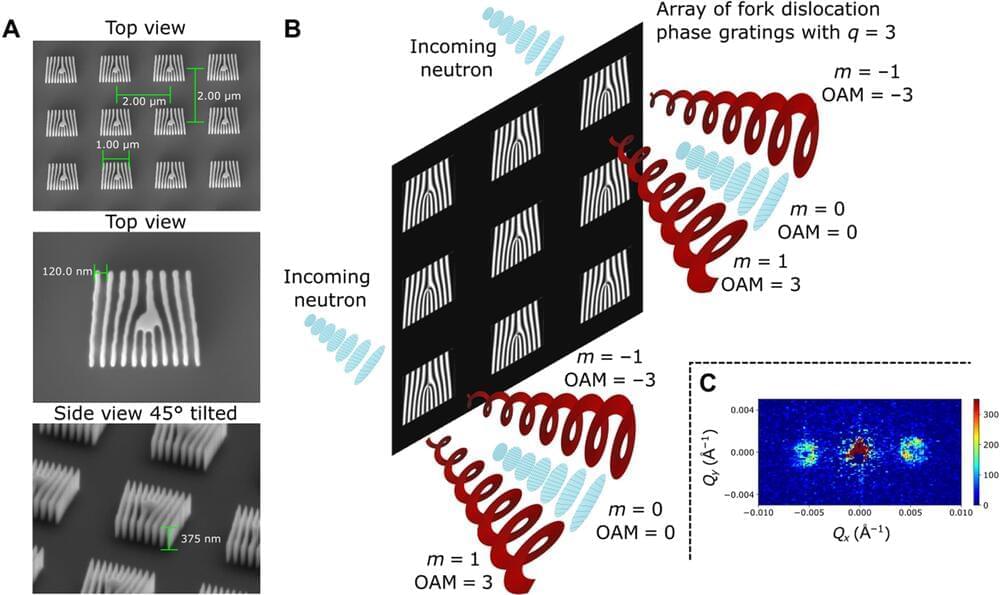

For the first time in experimental history, researchers at the Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC) have created a device that generates twisted neutrons with well-defined orbital angular momentum. Previously considered an impossibility, this groundbreaking scientific accomplishment provides a brand new avenue for researchers to study the development of next-generation quantum materials with applications ranging from quantum computing to identifying and solving new problems in fundamental physics.

“Neutrons are a powerful probe for the characterization of emerging quantum materials because they have several unique features,” said Dr. Dusan Sarenac, research associate with IQC and technical lead, Transformative Quantum Technologies at the University of Waterloo. “They have nanometer-sized wavelengths, electrical neutrality, and a relatively large mass. These features mean neutrons can pass through materials that X-rays and light cannot.”

While methods for the experimental production and analysis of orbital angular momentum in photons and electrons are well-studied, a device design using neutrons has never been demonstrated until now. Because of their distinct characteristics, the researchers had to construct new devices and create novel methods for working with neutrons.

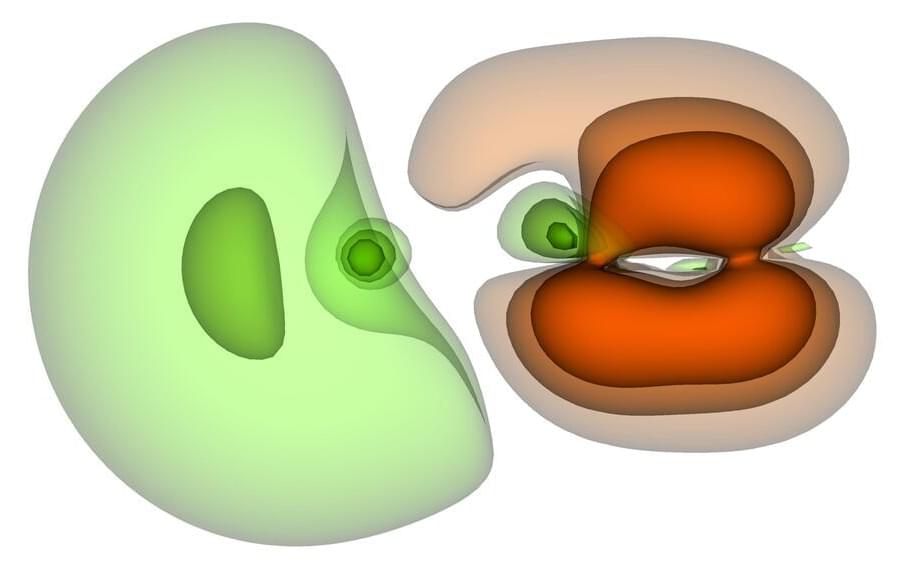

Researchers have investigated the capability of known quantum computing algorithms for fault-tolerant quantum computing to simulate the laser-driven electron dynamics of excitation and ionization processes in small molecules. Their research is published in the Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation.

“These quantum computer algorithms were originally developed in a completely different context. We used them here for the first time to calculate electron densities of molecules, in particular their dynamic evolution after excitation by a light pulse,” says Annika Bande, who heads a group on theoretical chemistry at Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers (HZB). Bande and Fabian Langkabel, who is doing his doctorate with her, show in the study how well this works.

“We developed an algorithm for a fictitious, completely error-free quantum computer and ran it on a classical server simulating a quantum computer of ten qubits,” says Langkabel. The scientists limited their study to smaller molecules in order to be able to perform the calculations without a real quantum computer and to compare them with conventional calculations.

By Wiktor Mazin, Jan-Rainer Lahmann, Emil Reinert and Bengt Wegner

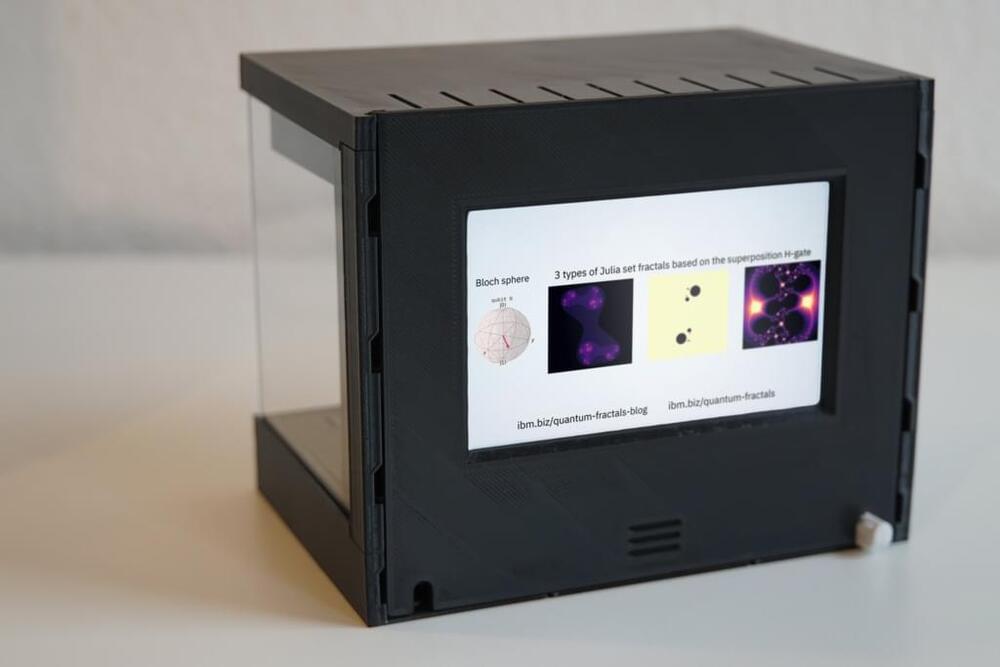

Creators are increasingly using Qiskit to make works of quantum art. And, combined with the Raspberry Pi, you have a unique platform to create portable installations beyond the realm of your laptop.

For this project, Wiktor Mazin, Jan-Rainer Lahmann, Emil Reinert and Bengt Wegner teamed up to demonstrate quantum fractals on the Raspberry Pi. We hope to show how to get creative with quantum computers thanks to the portability and ease-of-use of the RasQberry project, while providing a short guide on how you can create your own fractal animations using python code with Qiskit, both via a direct link and via an install on a Raspberry Pi.

Circa 2020 Basically this means a magnetic transistor can have not only quantum properties but also it can have nearly infinite speeds for processing speeds. Which means we can have nanomachines with near infinite speeds eventually.

Abstract The discovery of spin superfluidity in antiferromagnetic superfluid 3He is a remarkable discovery associated with the name of Andrey Stanislavovich Borovik-Romanov. After 30 years, quantum effects in a magnon gas (such as the magnon Bose–Einstein condensate and spin superfluidity) have become quite topical. We consider analogies between spin superfluidity and superconductivity. The results of quantum calculations using a 53-bit programmable superconducting processor have been published quite recently[1]. These results demonstrate the advantage of using the quantum algorithm of calculations with this processor over the classical algorithm for some types of calculations. We consider the possibility of constructing an analogous (in many respecys) processor based on spin superfluidity.