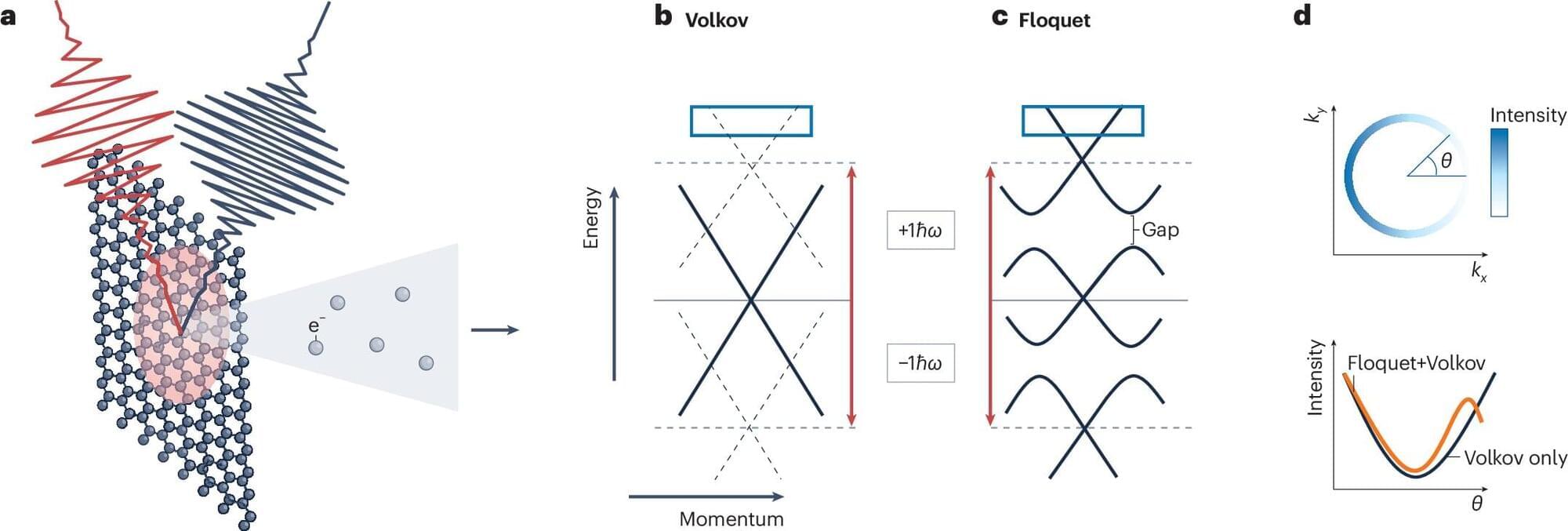

Electrons in graphene can act like a perfect fluid, defying established physical laws. This finding advances both fundamental science and potential quantum technologies.

For decades, quantum physicists have wrestled with a fundamental question: can electrons flow like a flawless, resistance-free liquid governed by a universal quantum constant? Detecting this unusual state has proven nearly impossible in most materials, since atomic defects, impurities, and structural imperfections disrupt the effect.

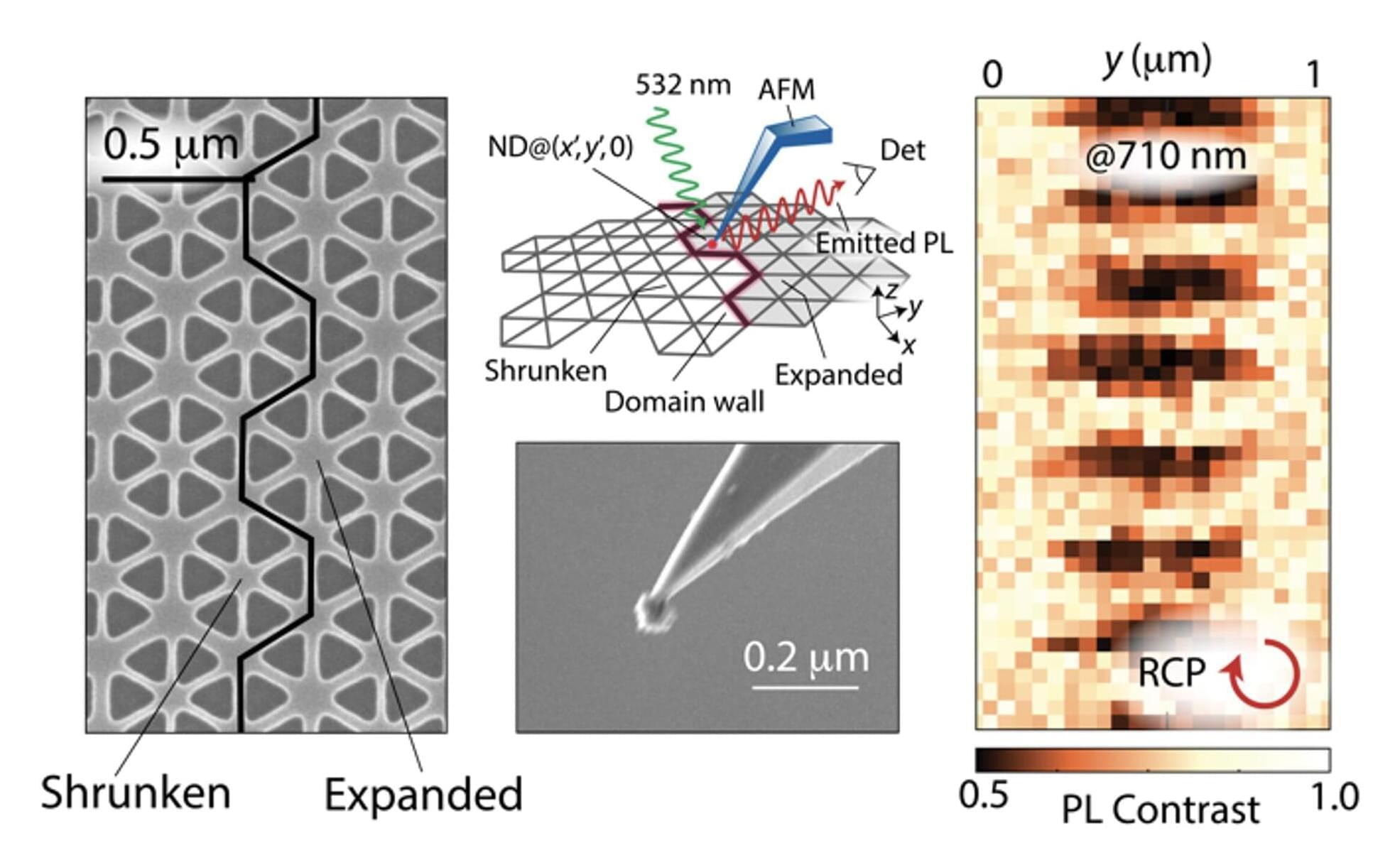

Detecting quantum fluids in graphene.