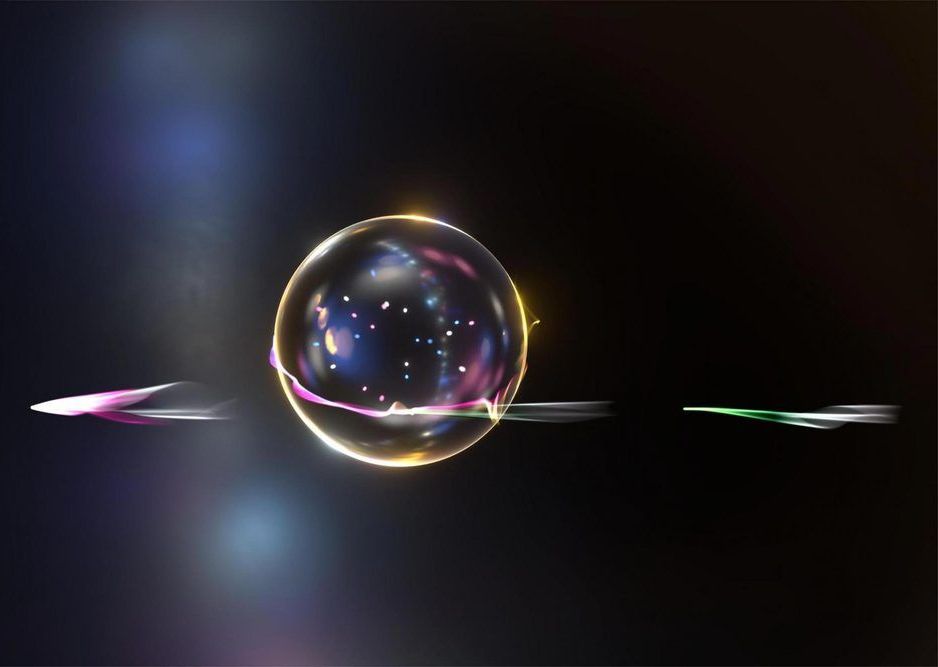

According to new research, black holes could be like a hologram, where all the information is amassed in a two-dimensional surface able to reproduce a three-dimensional image.

We can all picture that incredible image of a black hole that traveled around the world about a year ago. Yet, according to new research by SISSA, ICTP and INFN, black holes could be like a hologram, where all the information is amassed in a two-dimensional surface able to reproduce a three-dimensional image. In this way, these cosmic bodies, as affirmed by quantum theories, could be incredibly complex and concentrate an enormous amount of information inside themselves, as the largest hard disk that exists in nature, in two dimensions. This idea aligns with Einstein’s theory of relativity, which describes black holes as three dimensional, simple, spherical, and smooth, as they appear in that famous image. In short, black holes “appear” as three dimensional, just like holograms. The study which demonstrates it, and which unites two discordant theories, has recently been published in Physical Review X.

The mystery of black holes.