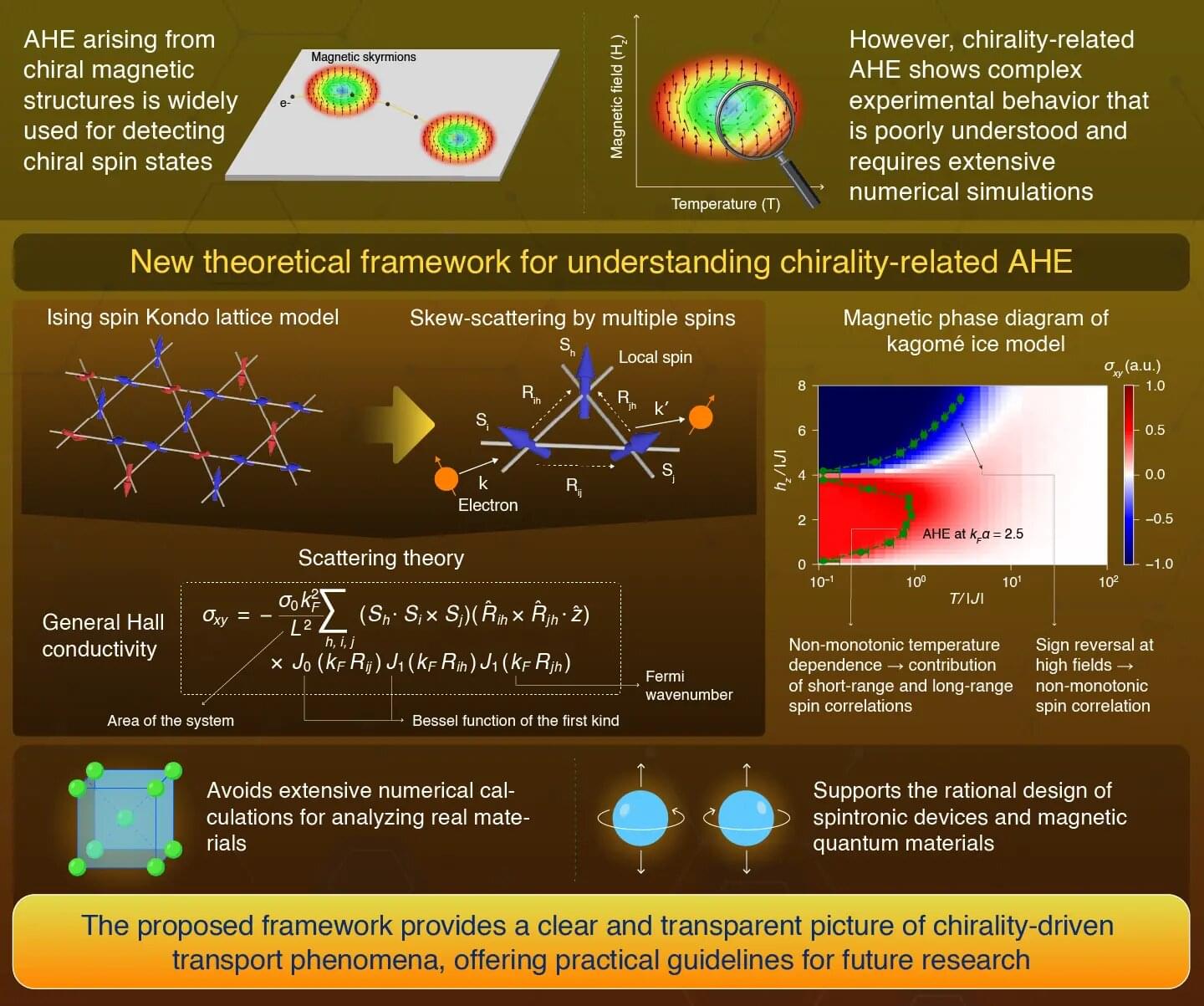

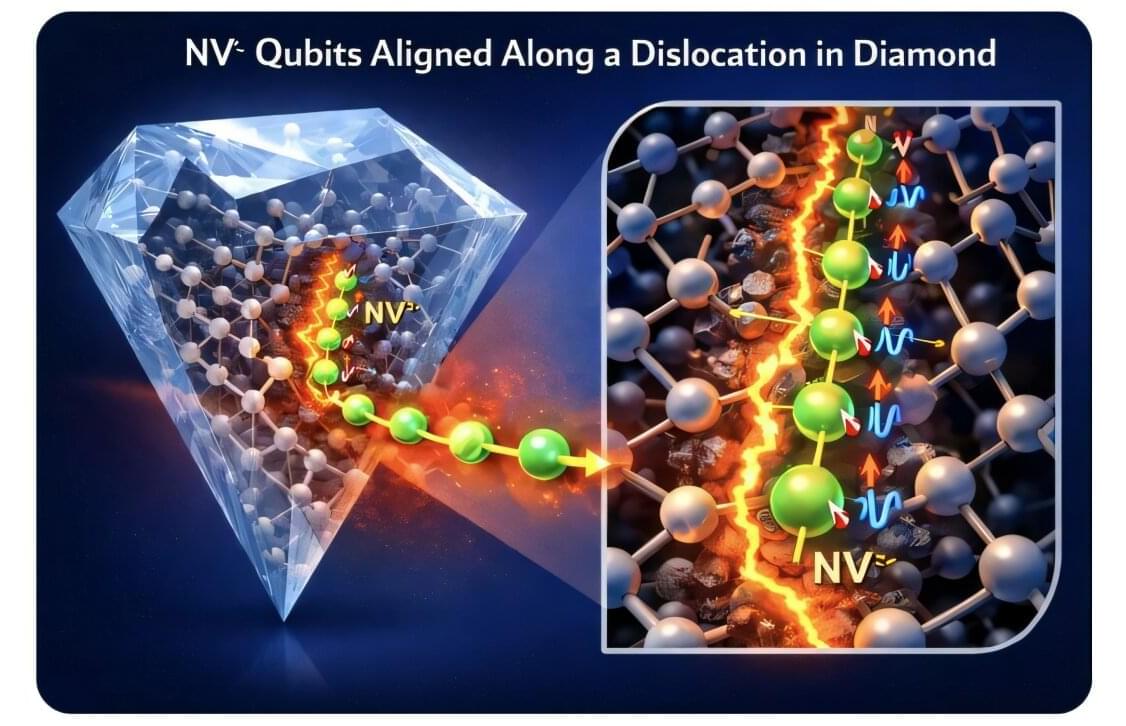

Neutron scattering and simulations reveal why a promising Kitaev candidate freezes into order instead of forming a quantum spin liquid.

Most magnets are predictable. Cool them down, and their tiny magnetic moments snap into place like disciplined soldiers. However, physicists have long suspected that, under the right conditions, magnetism might refuse to settle even in extreme cold.

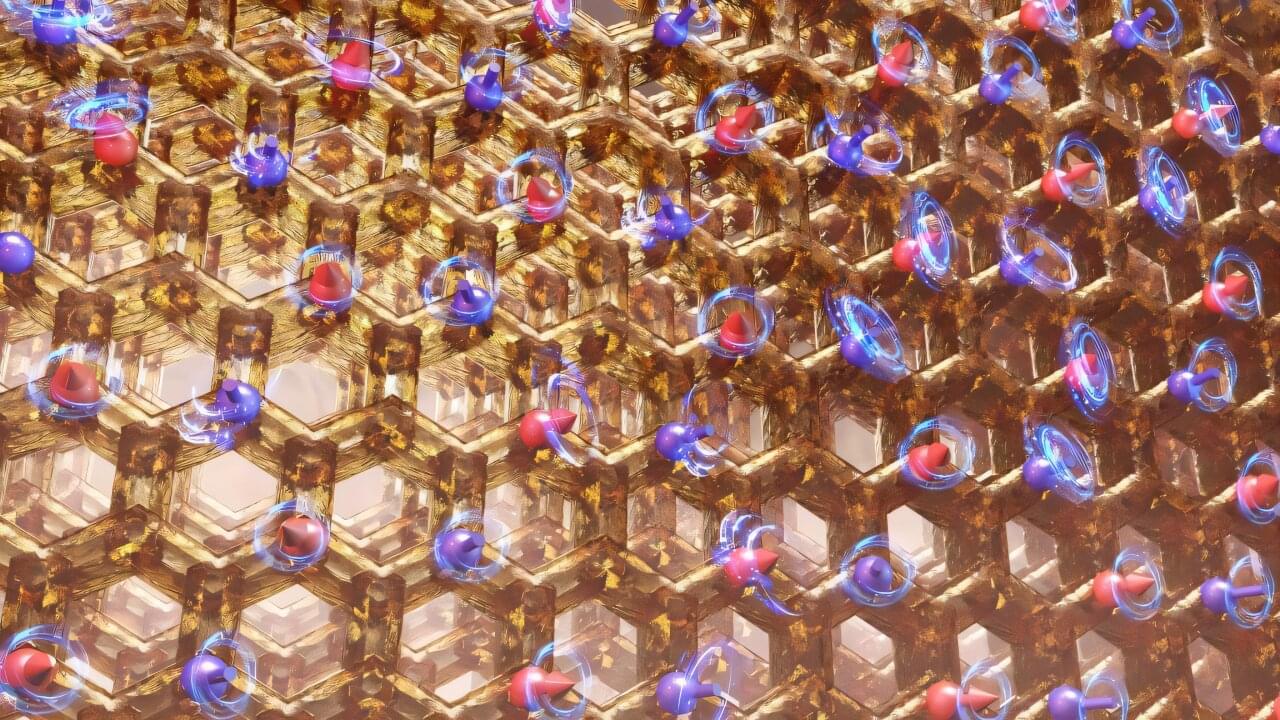

This restless state, known as a quantum spin liquid, could unlock new kinds of particles and serve as a foundation for quantum technologies that are far more stable than today’s fragile systems.

At Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), researchers have now created and closely examined a new magnetic material that brings this strange possibility a little closer to reality, even if it doesn’t quite cross the finish line yet.