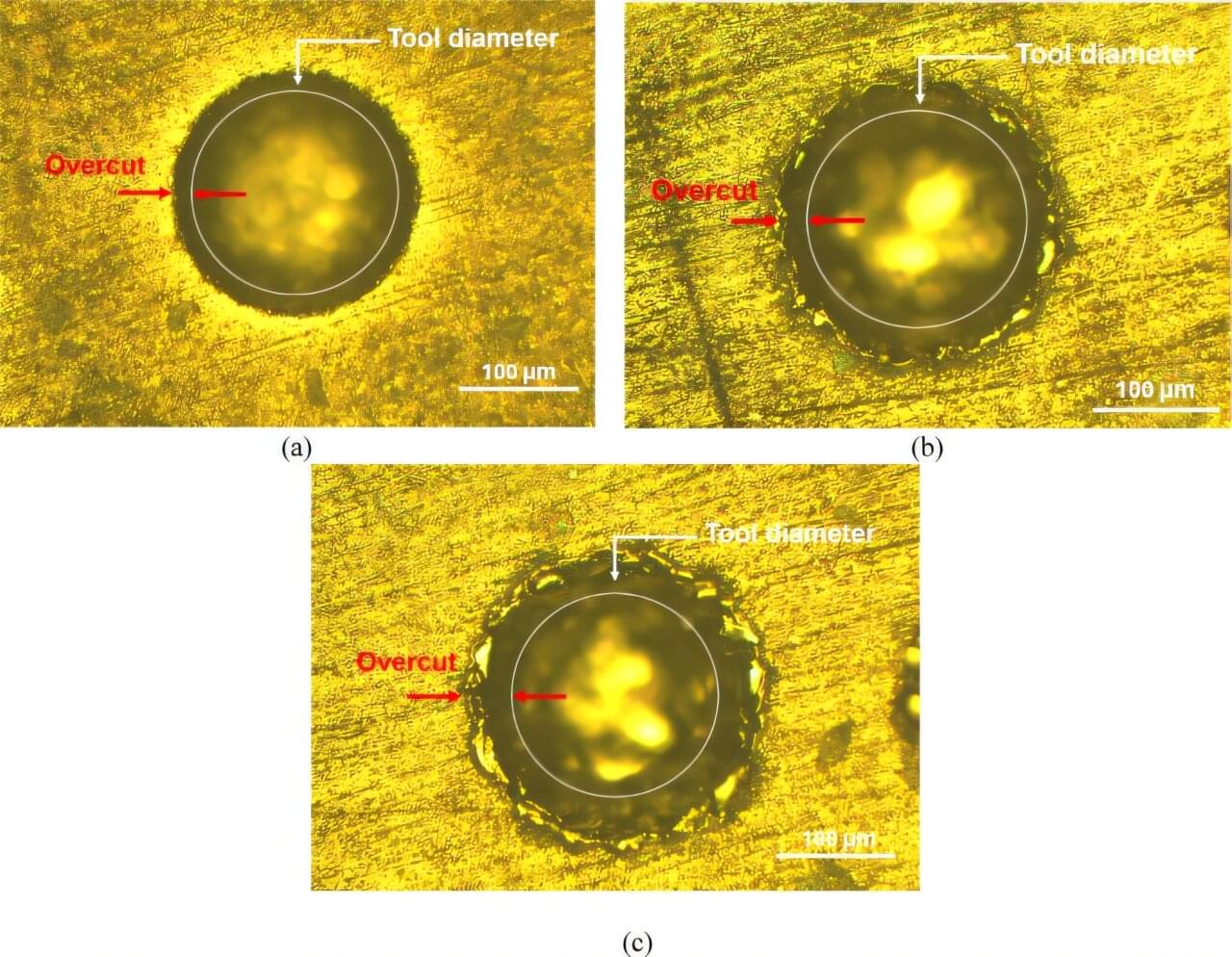

Researchers have developed a new machine-learning-assisted approach to optimize micro-electro-discharge machining (µ-EDM) of a next-generation biocompatible titanium alloy, potentially improving the manufacturing of advanced medical and aerospace components.

The work is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Titanium alloys are widely used in biomedical implants, aerospace systems, and automotive engineering due to their strength, corrosion resistance, and low weight. However, the commonly used alloy Ti–6Al–4V contains aluminum and vanadium, elements associated with long-term toxicity risks in biomedical applications.