When you look at text, you subconsciously track how much space remains on each line. If you’re writing “Happy Birthday” and “Birthday” won’t fit, your brain automatically moves it to the next line. You don’t calculate this—you *see* it. But AI models don’t have eyes. They receive only sequences of numbers (tokens) and must somehow develop a sense of visual space from scratch.

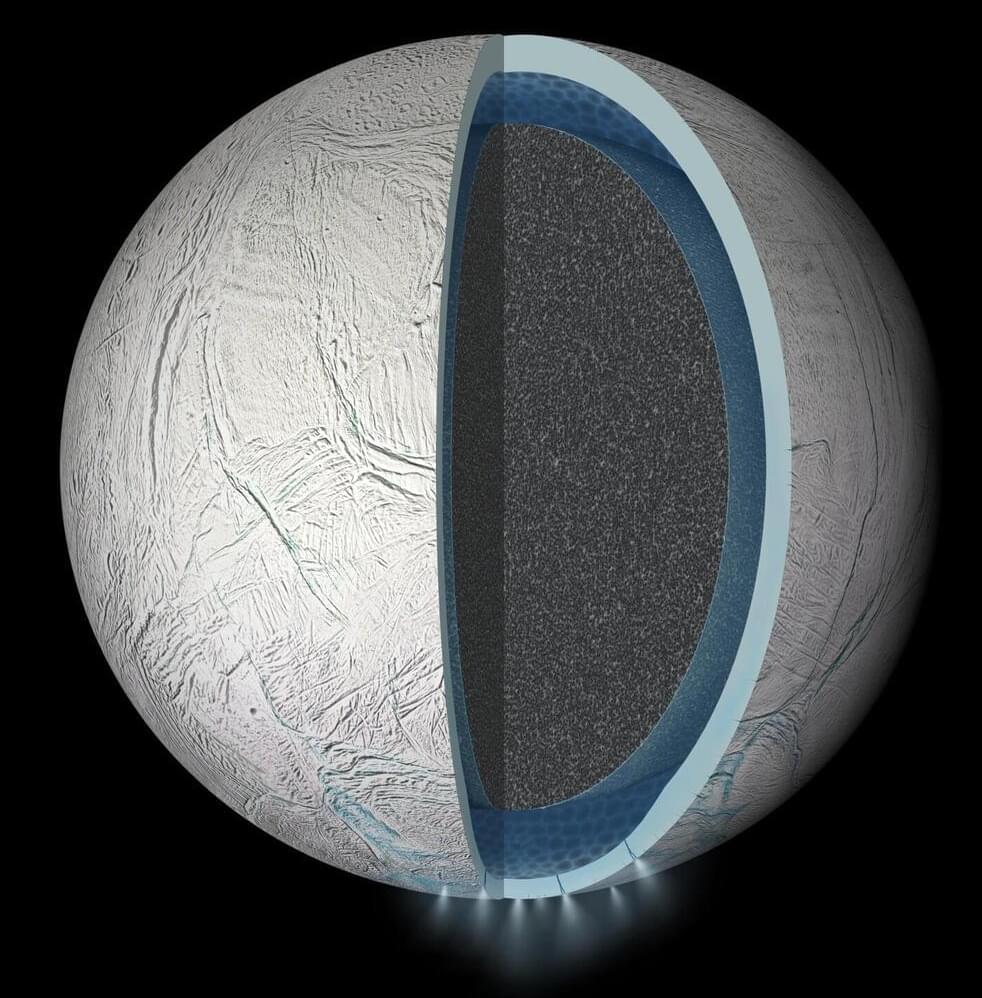

Inside your brain, “place cells” help you navigate physical space by firing when you’re in specific locations. Remarkably, Claude develops something strikingly similar. The researchers found that the model represents character counts using low-dimensional curved manifolds—mathematical shapes that are discretized by sparse feature families, much like how biological place cells divide space into discrete firing zones.

The researchers validated their findings through causal interventions—essentially “knocking out” specific neurons to see if the model’s counting ability broke in predictable ways. They even discovered visual illusions—carefully crafted character sequences that trick the model’s counting mechanism, much like optical illusions fool human vision.

2. Attention mechanisms are geometric engines: The “attention heads” that power modern AI don’t just connect related words—they perform sophisticated geometric transformations on internal representations.

1. What other “sensory” capabilities have models developed implicitly? Can AI develop senses we don’t have names for?

Language models can perceive visual properties of text despite receiving only sequences of tokens-we mechanistically investigate how Claude 3.5 Haiku accomplishes one such task: linebreaking in fixed-width text. We find that character counts are represented on low-dimensional curved manifolds discretized by sparse feature families, analogous to biological place cells. Accurate predictions emerge from a sequence of geometric transformations: token lengths are accumulated into character count manifolds, attention heads twist these manifolds to estimate distance to the line boundary, and the decision to break the line is enabled by arranging estimates orthogonally to create a linear decision boundary. We validate our findings through causal interventions and discover visual illusions—character sequences that hijack the counting mechanism.