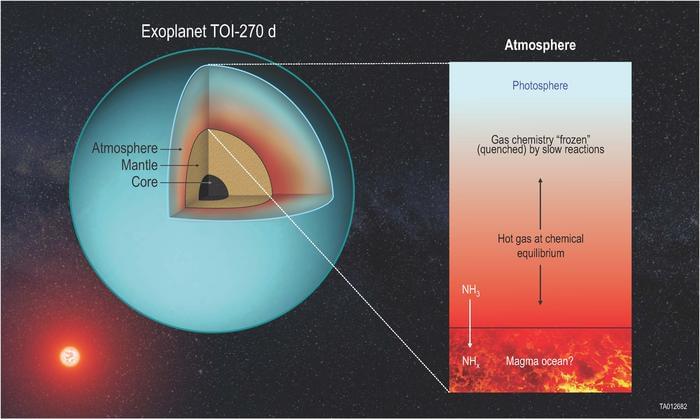

WASHINGTON (Reuters) –In a potential landmark discovery, scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope have obtained what they call the strongest signs y

Astronomers have discovered a planet that orbits at a 90-degree angle around a rare pair of strange stars—a real-life ‘twist’ on the fictional twin suns of Star Wars hero Luke Skywalker’s home planet of Tatooine.

The exoplanet, named 2M1510 (AB) b, orbits a pair of young brown dwarfs —objects bigger than gas-giant planets but too small to be proper stars. Only the second pair of eclipsing brown dwarfs known—this is the first exoplanet found on a right-angled path to the orbit of its two host stars.

An international team of researchers led by the University of Birmingham made the surprise discovery using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT). The brown dwarfs produce eclipses of one another, as seen from Earth, making them part of an “eclipsing binary.”

A pair of physicists at Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, in Argentina, have created a computer simulation of the famed Antikythera Mechanism and in so doing have found that manufacturing inaccuracies may have caused the device to jam so often it would have been very nearly unusable—if it was in the condition it is now. Esteban Szigety and Gustavo Arenas have posted a paper on the arXiv preprint server describing the factors that went into their simulation and what it showed.

In 1901, divers looking for sponges off the coast of the Greek island, Antikythera, discovered a mechanical device among the ruins of a sunken ship. The mysterious device was dated to the late second or early first century BCE, and from that time on there has been much debate in the scientific community regarding its purpose.

Some markings on the device suggest it could be used to track time and astronomical events and even predict some others, such as the arrival of a comet, courtesy of its intricate gears and pointing indicators, by turning its hand crank. Since only one of the devices has ever been found, some have suggested it had an otherworldly origin.

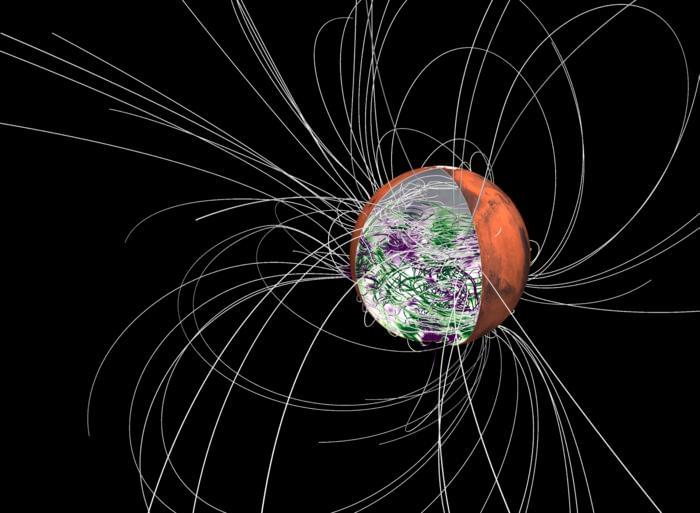

A QUT-led study analyzing data from NASA’s Perseverance rover has uncovered compelling evidence of multiple mineral-forming events just beneath the Martian surface—findings that bring scientists one step closer to answering the profound question: did life ever exist on Mars?

The QUT research team led by Dr. Michael Jones, from the Central Analytical Research Facility and the School of Chemistry and Physics, includes Associate Professor David Flannery, Associate Professor Christoph Schrank, Brendan Orenstein and Peter Nemere, together with researchers from North America and Europe.

The paper, “In-situ crystallographic mapping constrains sulfate precipitation and timing in Jezero crater, Mars” is published in Science Advances.

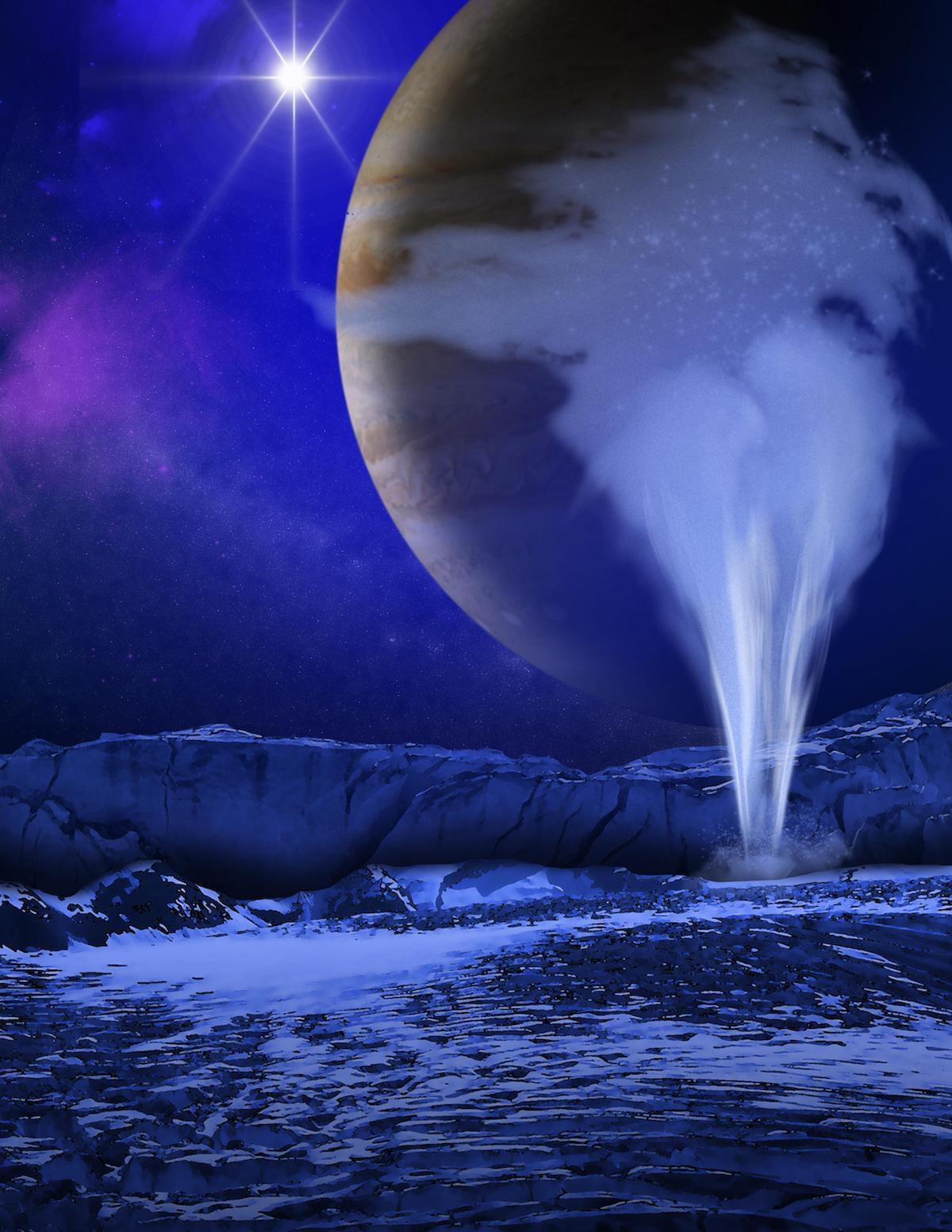

The study notes, “These findings underscore the complexity of Europa’s plume activity. Our results provide a framework to explore various plume characteristics, including gas drag, particle size, initial ejection velocities, and gas production rates, and the resulting plume morphologies and deposition outcomes.”

How do the water vapor plumes on Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, contribute to the interaction between the moon’s surface and subsurface environments? This is what a recent study published in The Planetary Science Journal hopes to address as a team of researchers investigated how gas drag could influence the direction of particles being emitted by Europa’s water vapor plumes, specifically regarding where they land on the surface, either near the plumes or farther out. This study has the potential to help scientists better understand the surface-subsurface interactions on Europa and what this could mean for finding life as we know it.

Artist’s illustration of Europa’s water vapor plumes. (Credit: NASA/ESA/K. Retherford/SWRI)

For the study, the researchers used a series of computer models to simulate how the speed and direction of dust particles emitted from the plumes could be influenced by a process called gas drag, which could decrease the speed and direction of dust particles exiting the plumes. In the end, the researchers found that gas drag greatly influences dust behavior, with smaller dust particles ranging in size from 0.001 to 0.1 micrometers becoming more spread out after eruption and larger dust particles ranging in size from 0.1 to 10 micrometers landing near the plume sites.