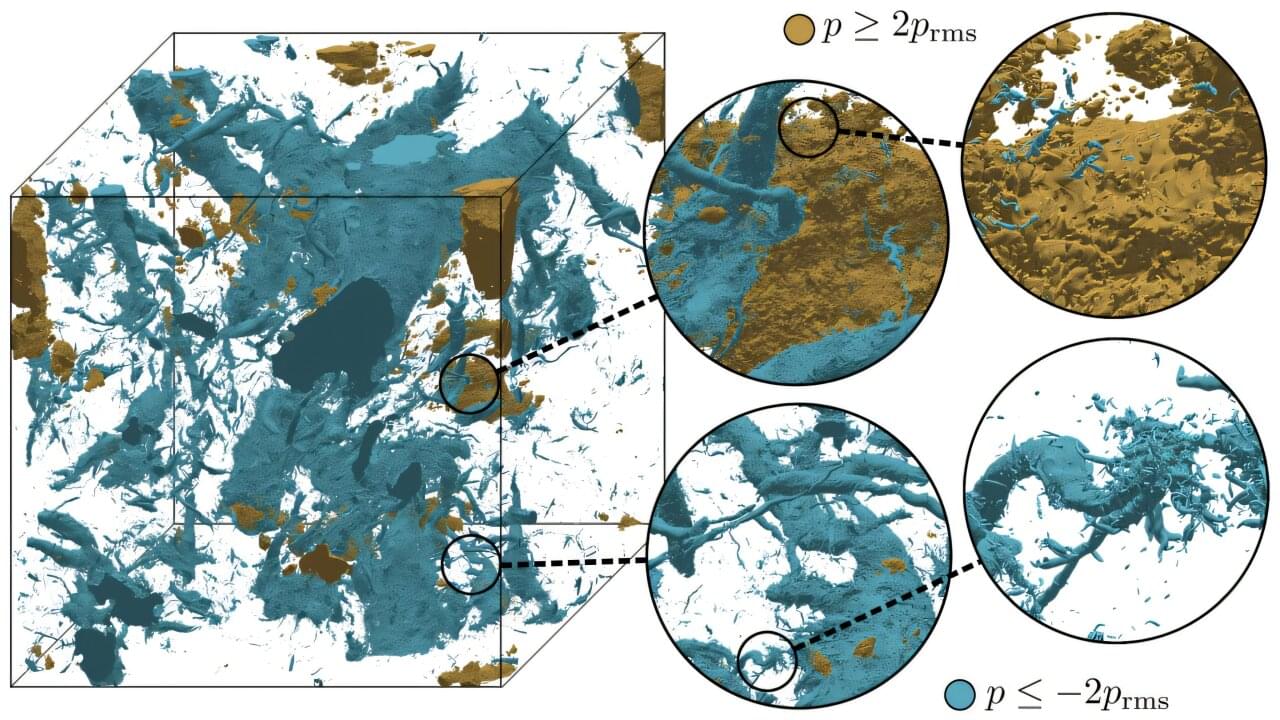

Using the Frontier supercomputer at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology have performed the largest direct numerical simulation (DNS) of turbulence in three dimensions, attaining a record resolution of 35 trillion grid points. Tackling such a complex problem required the exascale (1 billion billion or more calculations per second) capabilities of Frontier, the world’s most powerful supercomputer for open science.

The team’s results offer new insights into the underlying properties of the turbulent fluid flows that govern the behaviors of a variety of natural and engineered phenomena—from ocean and air currents to combustion chambers and airfoils. Improving our understanding of turbulent fluctuations can lead to practical advancements in many areas, including more accurately predicting the weather and designing more efficient vehicles.

The work is published in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics.