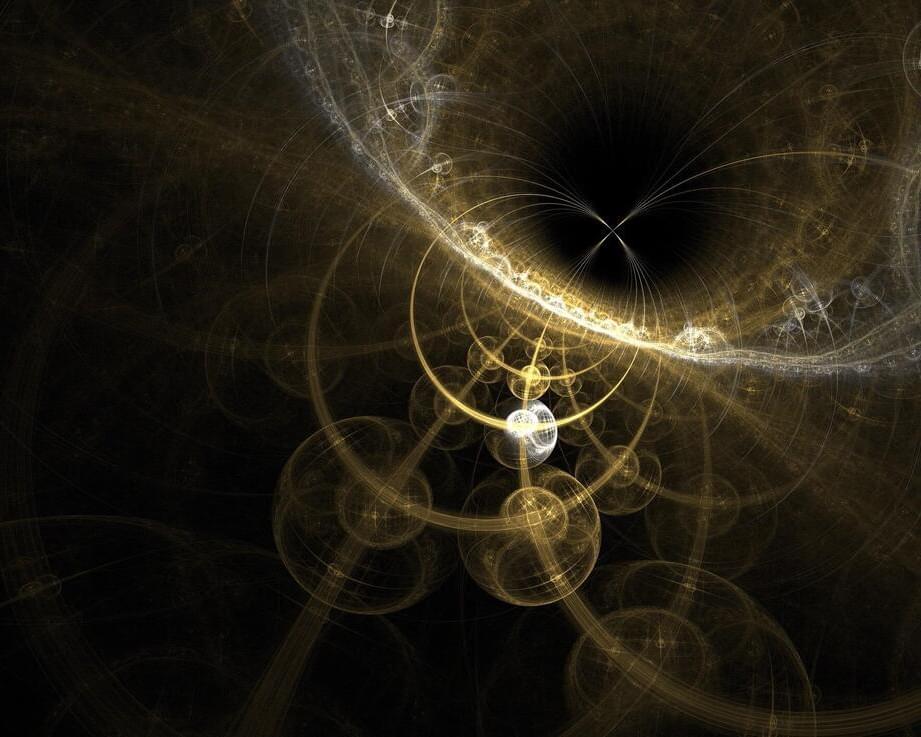

In their pursuit of understanding cosmic evolution, scientists rely on a two-pronged approach. Using advanced instruments, astronomical surveys attempt to look farther and farther into space (and back in time) to study the earliest periods of the Universe. At the same time, scientists create simulations that attempt to model how the Universe has evolved based on our understanding of physics. When the two match, astrophysicists and cosmologists know they are on the right track!

In recent years, increasingly-detailed simulations have been made using increasingly sophisticated supercomputers, which have yielded increasingly accurate results. Recently, an international team of researchers led by the University of Helsinki conducted the most accurate simulations to date. Known as SIBELIUS-DARK, these simulations accurately predicted the evolution of our corner of the cosmos from the Big Bang to the present day.

In addition to the University of Helsinki, the team was comprised of researchers from the Institute for Computational Cosmology (ICC) and the Centre for Extragalactic Astronomy at Durham University, the Lorentz Institute for Theoretical Physics at Leiden University, the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, and The Oskar Klein Centre at Stockholm University. The team’s results are published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.