Researchers at Aalto University have discovered a new force acting on water droplets moving over superhydrophobic surfaces like black silicon by adapting a novel force measurement technique to uncover the previously unidentified physics at play. This force, identified as air-shearing, challenges previous understandings and suggests modifications in the design of these surfaces to reduce drag, potentially improving their efficiency and application in various fields.

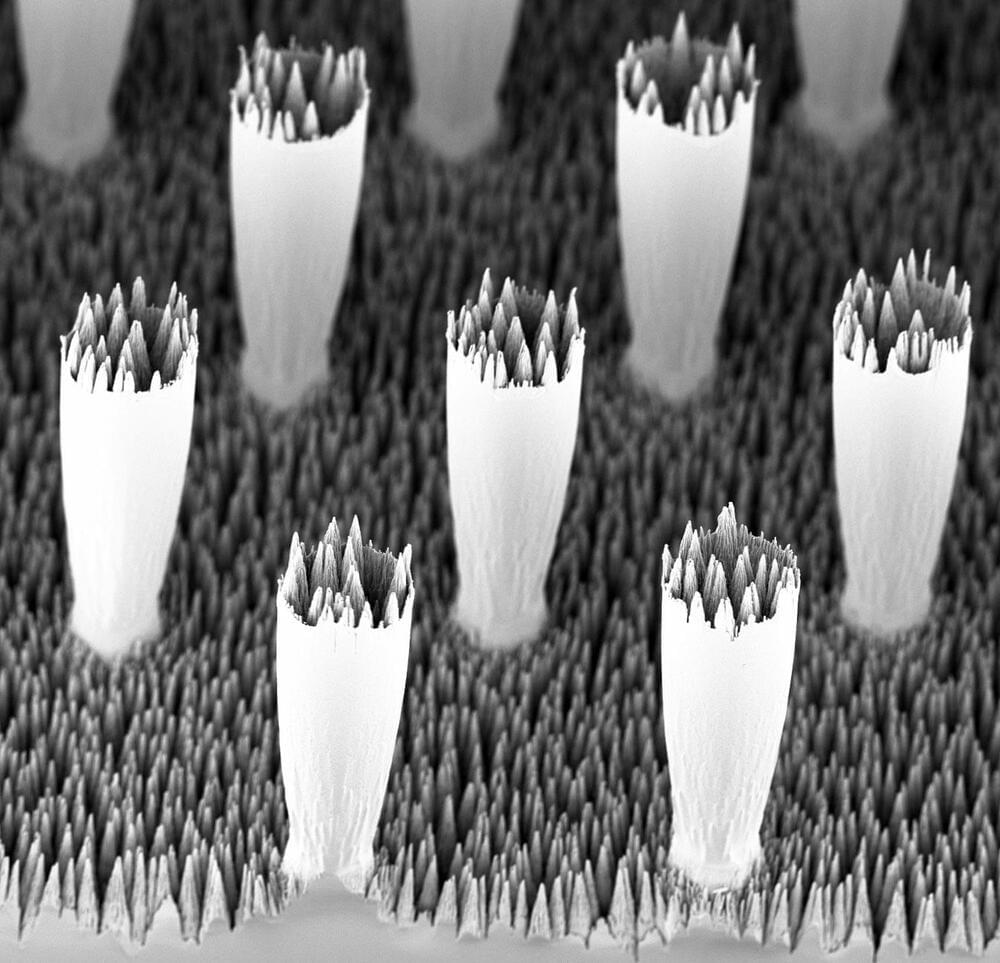

Microscopic chasms forming a sea of conical jagged peaks stipple the surface of a material called black silicon. While it’s commonly found in solar cell tech, black silicon also moonlights as a tool for studying the physics of how water droplets behave.

Black silicon is a superhydrophobic material, meaning it repels water. Due to water’s unique surface tension properties, droplets glide across textured materials like black silicon by riding on a thin air-film gap trapped beneath. This works great when the droplets move slowly—they slip and slide without a hitch.