MIT researchers developed a new type of bionic knee that can help people with above-the-knee amputations walk faster, climb stairs, and avoid obstacles more easily than they could with a traditional prosthesis.

Directly connected to bone, the leg allows wearers to climb stairs, walk at a normal speed, and kick balls.

A new bionic knee allows amputees to walk faster, climb stairs more easily, and adroitly avoid obstacles, researchers reported in the journal Science.

The new prothesis is directly integrated with the person’s muscle and bone tissue, enabling greater stability and providing more control over its movement, researchers said.

Two people equipped with the prosthetic said the limb felt more like a part of their own body, the study says.

Big News! My New Audiobook The Intelligence Supernova is Now Live! 🎧 I’m thrilled to announce the release of the audiobook edition of The Intelligence Supernova: Essays on Cybernetic Transhumanism, the Simulation Singularity & the Syntellect Emergence. This project has been incredibly close to my heart—it dives deep into the unfolding convergence of advanced AI, consciousness, and our collective evolution beyond biology. In this book, I explore the concept of the “Intelligence Supernova”—a coming explosion of synthetic and post-biological intelligence that may soon give rise to a planetary-scale mind, the Syntellect. It’s a philosophical and scientific journey that challenges you to imagine what lies beyond the Technological Singularity: digital immortality, mind-uploading, the emergence of infomorphs, and the architecture of a conscious Universe. This audiobook is for futurists, technophilosophers, and all curious minds ready to glimpse humanity’s metamorphic future. If you’re drawn to ideas like cybernetic immortality, experiential realism, or the Omega Point Cosmology, I think you’ll find this work especially meaningful.

Now available on Amazon: Audible: https://www.audible.com/pd/The-Intelligence-Supernova-Audiobook/B0FGZ3JMPM #IntelligenceSupernova #CyberneticTranshumanism #SimulationSingularity #SyntellectEmergence #SyntellectHypothesis #cybernetics #singularity #transhumanism #posthumanism #AGI #superintelligence

Amazon.com: The Intelligence Supernova: Essays on Cybernetic Transhumanism, The Simulation Singularity & The Syntellect Emergence (Audible Audio Edition): Alex M. Vikoulov, Ecstadelic Media Group, Virtual Voice: Books.

Zoltan Istvan, a leading transhumanist, proposes a new economic model for the age of AI and robots.

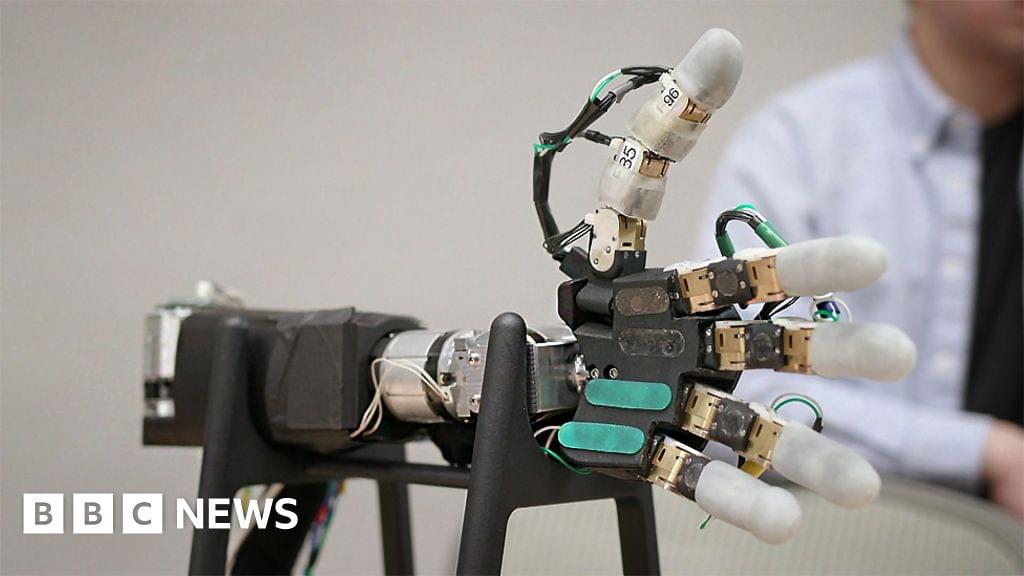

I was born without lower arms and legs, so I’ve been around prosthetics of all shapes and sizes for as long as I can remember.

I’ve actively avoided those designed for upper arms for most of my adult life, so have never used a bionic hand before.

But when I visited a company in California, which is seeking to take the technology to the next level, I was intrigued enough to try one out — and the results were, frankly, mind-bending.

Prosthetic limbs have come a long way since the early days when they were fashioned out of wood, tin and leather.

Modern-day replacement arms and legs are made of silicone and carbon fibre, and increasingly they are bionic, meaning they have various electronically controlled moving parts to make them more useful to the user. (Feb 2024)

BBC Click reporter Paul Carter tries out a high-tech prosthetic promising a ‘full range of human motion’

Are human cyborgs the future? You won’t believe how close we are to merging humans with machines! This video uncovers groundbreaking advancements in cyborg technology, from bionic limbs and brain-computer interfaces to biological robots like anthrobots and exoskeletons. Discover how these innovations are reshaping healthcare, military, and even space exploration.

Learn about real-world examples, like Neil Harbisson, the colorblind cyborg artist, and the latest developments in brain-on-a-chip technology, combining human cells with artificial intelligence. Explore how cyborg soldiers could revolutionize the battlefield and how genetic engineering might complement robotic enhancements.

The future of human augmentation is here. Could we be on the verge of transforming humanity itself? Dive in to find out how science fiction is quickly becoming reality.

How do human cyborgs work? What are the latest AI breakthroughs in cyborg technology? How are cyborgs being used today? Could humans evolve into hybrid beings? This video answers all your questions. Don’t miss it!

#ai.

#cyborg.

#ainews.

====================================

Francesca Ferrando‘s Philosophical Posthumanism is a must-read for transhumanists and non-transhumanists alike. Check out her interview to find more!