PCNA–PAF15 has a key role in determining replisome dynamics during genome replication and protecting against genome instability.

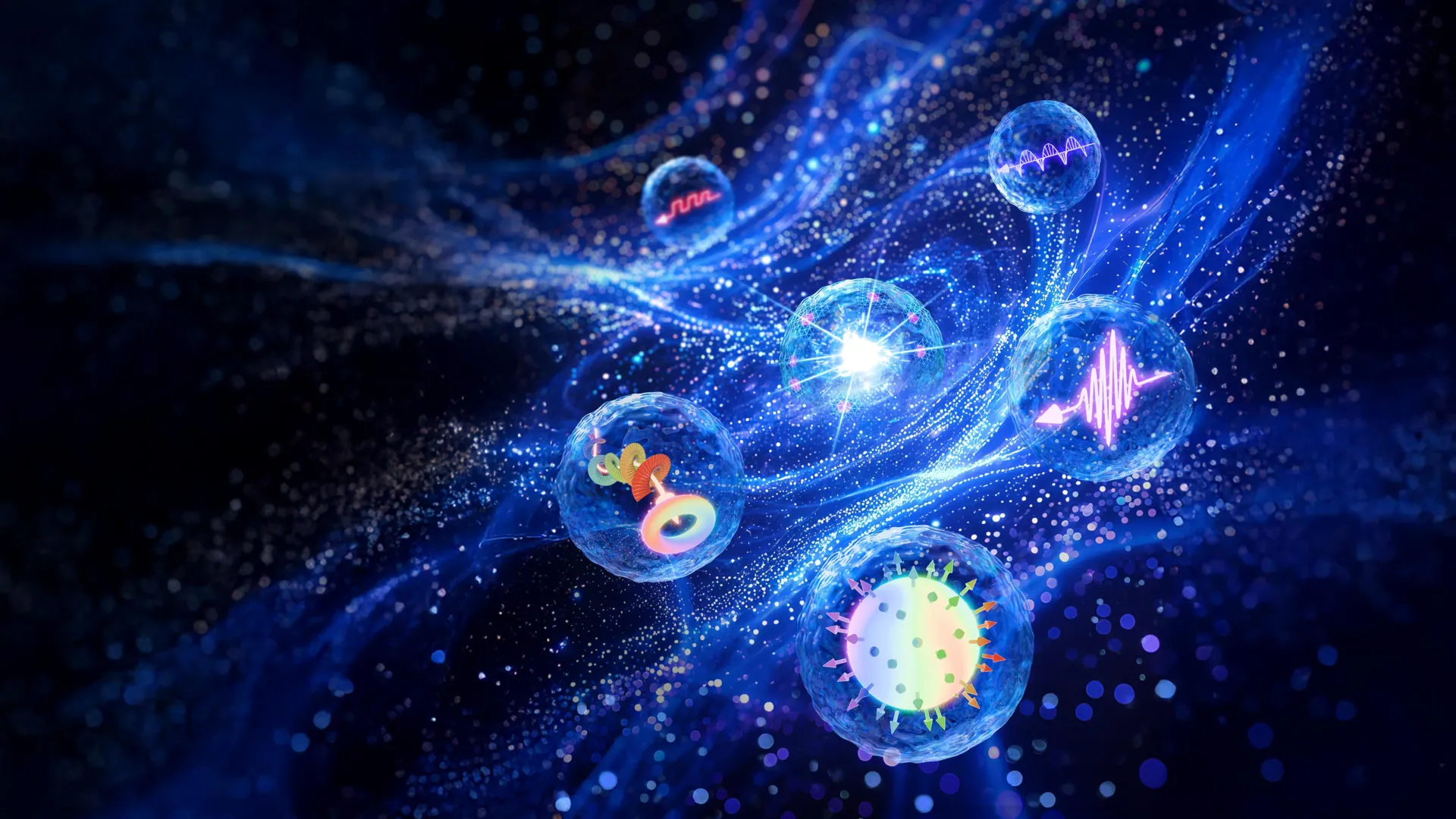

Researchers have discovered new ways to shape quantum light, creating high-dimensional states that can carry much more information per photon. Using advanced tools like on-chip photonics and ultrafast light structuring, they’re pushing quantum communication and imaging into exciting new territory. Although long-distance transmission remains tricky, innovative approaches—such as topological quantum states—could make these fragile signals far more resilient. The momentum suggests quantum optics is entering a bold new phase.

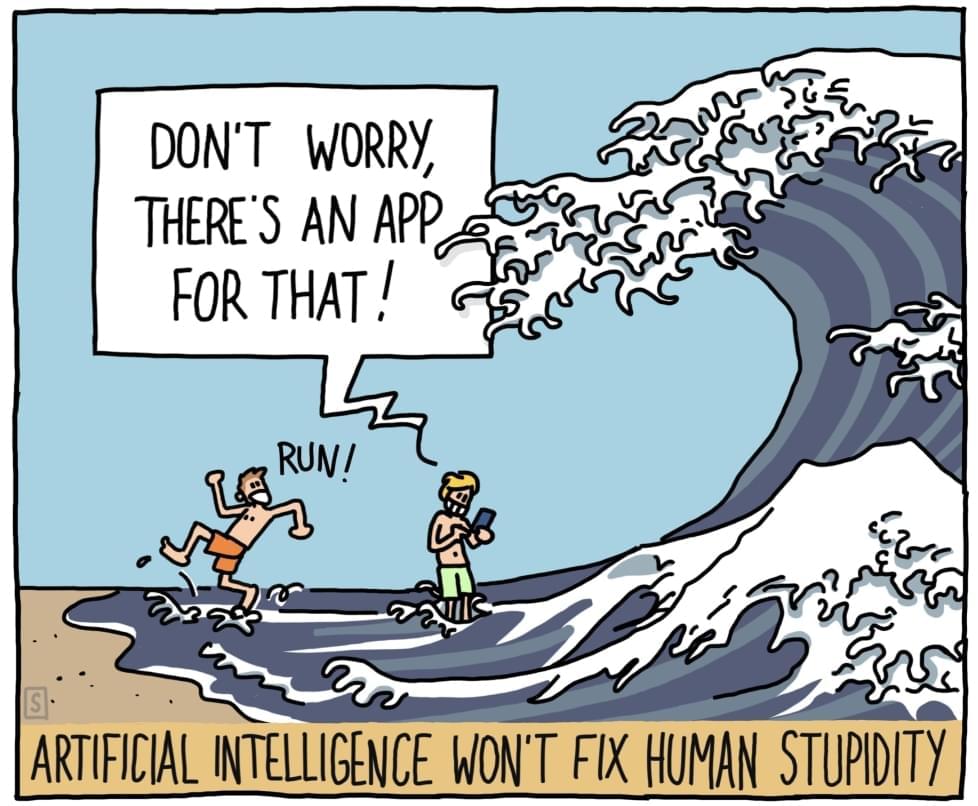

Fifteen years ago, I wrote something that annoyed many techno-optimists.

Ten years ago, I filmed it as a podcast.

Today it feels less controversial — and more urgent.

Technology is NOT Enough.

We have the science to feed everyone. We have the tech to provide clean water. We understand climate change. We know how to reduce suffering.

And yet we don’t act.

Workshop on quantum aspects of black holes and spacetime.

Topic: Comments on the Hartle-Hawking state and observers.

Speaker: Ying Zhao.

Affiliation: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Date: December 3, 2025

Wolfensohn Hall.

It was argued that any fixed holographic theory contains only one closed universe state and hence fails to give semi-classical physics. It was proposed that this problem can be resolved by including a classical observer living inside the universe. Earlier works focused on closed universes connected with asymptotic Euclidean boundaries. In this talk we examine the case of Hartle-Hawking state where the dominant Euclidean topology is a sphere. We show that different features emerge. We comment on the potential implications for the understanding of de Sitter space. Based on work with Daniel Harlow.

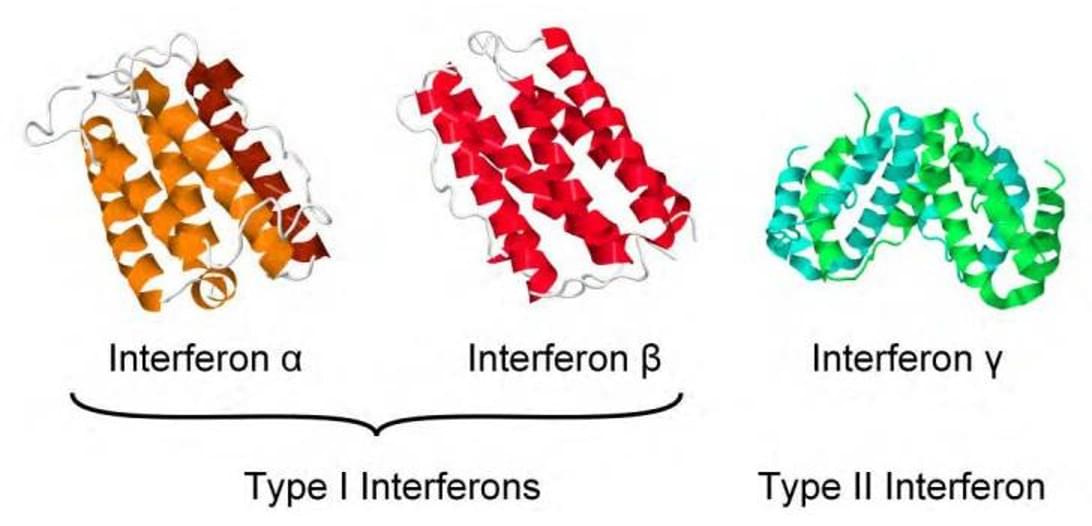

(IFNs) are a family of antiviral and immunomodulatory signaling proteins produced by host cells to fight pathogens like viruses, bacteria, and tumors.

As cytokines, they alert neighboring cells to activate defenses, inhibit viral replication, and regulate immune responses.

Common uses include treating hepatitis B and C, multiple sclerosis, and certain cancers like melanoma and lymphoma.

For more information click on the link below: sciencenewshighlights ScienceMission.

Researchers from Skoltech have published a paper in the journal Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena presenting an analysis of steady propagating combustion waves—from slow flames to supersonic detonation waves. The study relies on the authors’ mathematical model, which captures the key physical properties of complex combustion processes and yields accurate analytical and numerical solutions. The findings are important for understanding the physical mechanisms behind the transition from deflagration to detonation, as well as for developing safer engines, fuel combustion systems, and protection against unwanted explosions in industrial settings.

The scientists identified several main types of combustion waves. The most powerful is strong detonation —a supersonic shock wave that sharply compresses and heats the mixture, triggering a chemical reaction. This type of wave is highly stable. In weak detonations and weak deflagration waves, there is no abrupt shock front.

The chemical reaction only begins if the mixture has been preheated to a temperature where it can ignite. These regimes occur rarely, under specific conditions, and can easily break down or transition into another wave type.

A study published in the Chemical Engineering Journal proposes a new approach to environmental remediation of pharmaceutical pollutants in water flows. This approach is based on a phenomenon known as “sparks,” which refers to the sparks that appear on the surface of a metal when it is subjected to plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO).

During PEO, a metal part (in this case, aluminum) is immersed in a liquid to which an electrical voltage is applied. This results in the growth of an oxide coating. During the process, micro-electrical discharges, or sparks, appear. These sparks last for fractions of a second and cover a small area. However, they lead to very high temperatures, which is why they are nicknamed the “second sun.” This treatment is used on aluminum, magnesium, titanium, and other metal parts in the aerospace, automotive, medical, and electronics industries to create an oxide coating that improves the resistance of the material to corrosion and heat.

Nature does it again! The natural world has a knack for giving us the blueprints for some useful technologies, and the humble sea urchin is the latest contributor. Scientists have designed a new class of smart sensors by mimicking the internal architecture found in their spines.

Sea urchins are covered in movable spines that have long been thought of as a form of deterrent and protection against predators. But according to a new study published in the journal Nature, they are also sophisticated sensing tools.

Shield and sensor.

The world is never really at rest. Even in a vacuum near ultracold temperatures where all classical motion should come to a halt, you’ll find quantum fluctuations. In thin, two-dimensional materials, these include random vibrations that can alter electromagnetic fields, a feature that theorists have posited could be quite useful for modifying materials.

“It’s a holy grail we’ve been searching for decades,” said Dmitri Basov, Higgins Professor of Physics at Columbia. “We believe we’ve found it.”

In a new paper published in Nature, Basov and 32 collaborators from 17 institutions came together to confirm that quantum fluctuations alone from the vacuum inside atom-thin layers of 2D materials can alter the properties of a larger nearby crystal—a theoretical possibility now experimentally realized for the first time.