Can conscious self-awareness be coded in an algorithm? According to distinguished computer scientist Lenore Blum and Turing Award Laureate Manuel Blum the answer is \.

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Flavors of Computation Are Flavors of Consciousness

If we don’t understand why we’re conscious, how come we’re so sure that extremely simple minds are not? I propose to think of consciousness as intrinsic to computation, although different types of computation may have very different types of consciousness – some so alien that we can’t imagine them. Since all physical processes are computations, this view amounts to a kind of panpsychism. How we conceptualize consciousness is always a sort of spiritual poetry, but I think this perspective better accounts for why we ourselves are conscious despite not being different in a discontinuous way from the rest of the universe. Introduction ‘don’t hold strong opinions about things you don’t understand’ —Derek Hess Susan Blackmore believes the way we typically […].

Jesus’ Divine Birth Myth Was Modeled After Alexander The Great | Dr. Richard C. Miller

Enjoy the videos and music you love, upload original content, and share it all with friends, family, and the world on YouTube.

Creating Life’s Operating System

Have we created an operating system for life? How close are we to cloning humans, and what would that even look like?

You’re in for a fascinating episode as the line between science and science fiction gets blurred. My guest is microbiologist and geneticist Andrew Hessel, the CEO and Founder of The Genome Project-Write, and author of \.

Harnessing Automated Insulin Delivery: Case Reports from Marathon Runners with Type 1 Diabetes

How can machine learning help individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D)? This is what a study presented at this year’s Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) hopes to address as a team of researchers have developed a system using machine learning capable of managing blood sugars levels with such proficiency that those using system were able to lead lives far more active than the average T1D patient.

For the study, the researchers developed the AID system, which uses closed-loop technology that delivers insulin based on readings from the machine learning algorithm, resulting in a 50-year-old man, a 40-year-old man, and a 34-year-old woman with T1D being able to run hours-long marathons in Tokyo, Santiago, and Paris, respectively. This study holds the potential to help develop better technology capable of allowing T1D diabetes patients to stay in shape without constantly fearing for their blood sugar levels, which can lead to long-term health problems, including hyperglycemia, nerve damage, or a heart attack.

“Despite better systems for monitoring blood sugars and delivering insulin, maintaining glucose levels in target range during aerobic training and athletic competition is especially difficult,” said Dr. Maria Onetto, who is in the Department of Nutrition at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile and lead author of the study. “The use of automated insulin delivery technology is increasing, but exercise continues to be a challenge for individuals with T1D, who can still struggle to reach the recommended blood sugar targets.”

Cats have brain activity recorded with the help of crocheted hats

Custom-made wool caps have enabled scientists to record electroencephalograms in awake cats for the first time, which could help assess their pain levels.

Wormhole: A wormhole is a hypothetical structure connecting disparate points in spacetime, and is based on a special solution of the Einstein field equations

A wormhole is a hypothetical structure connecting disparate points in spacetime, and is based on a special solution of the Einstein field equations. [ 1 ]

A can be visualized as a tunnel with two ends at separate points in spacetime (i.e., different locations, different points in time, or both).

Wormholes are consistent with the general theory of relativity, but whethers actually exist is uncertain. Many scientists postulate thats are merely projections of a fourth spatial dimension, analogous to how a two-dimensional (2D) being could experience only part of a three-dimensional (3D) object. [ 2 ] A well-known analogy of such constructs is provided by the Klein bottle, displaying a hole when rendered in three dimensions but not in four or higher dimensions.

Researchers discover new way to make ‘atomic lasagna’

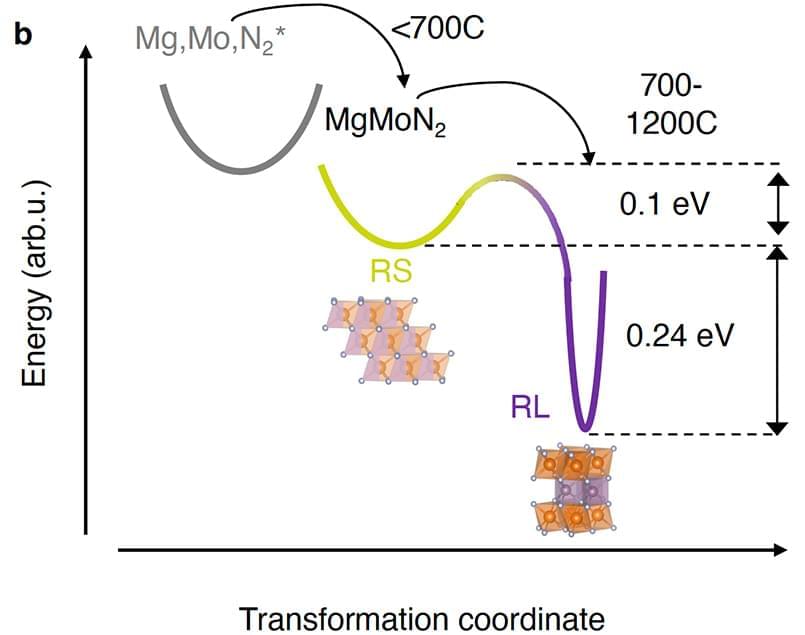

A research team discovered a method to transform materials with three-dimensional atomic structures into nearly two-dimensional structures – a promising advancement in controlling their properties for chemical, quantum, and semiconducting applications.

The field of materials chemistry seeks to understand, at an atomic level, not only the substances that comprise the world but also how to intentionally design and manufacture them. A pervasive challenge in this field is the ability to precisely control chemical reaction conditions to alter the crystal structure of materials—how their atoms are arranged in space with respect to each other. Controlling this structure is critical to attaining specific atomic arrangements that yield unique behaviors. This process results in novel materials with desirable characteristics for practical applications.

A team of researchers led by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), with contributions from the Colorado School of Mines (Mines), National Institute of Standards and Technology, and Argonne National Laboratory, discovered a method to convert materials from their higher-energy (or metastable) state to their lower-energy, stable state while instilling an ordered and nearly two-dimensional arrangement of atoms—a feat that has the potential to unleash promising material properties.

Quantinuum accelerates the path to Universal Fully Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing

More recently, in a period where we upgraded our H2 system from 32 to 56 qubits and demonstrated the scalability of our QCCD architecture, we also hit a quantum volume of over two million, and announced that we had achieved “three 9’s” fidelity, enabling real gains in fault-tolerance – which we proved within months as we demonstrated the most reliable logical qubits in the world with our partner Microsoft.

We don’t just promise what the future might look like; we demonstrate it.

Today, at Quantum World Congress, we shared how recent developments by our integrated hardware and software teams have, yet again, accelerated our technology roadmap. It is with the confidence of what we’ve already demonstrated that we can uniquely announce that by the end of this decade Quantinuum will achieve universal fully fault-tolerant quantum computing, built on foundations such as a universal fault-tolerant gate set, high fidelity physical qubits uniquely capable of supporting reliable logical qubits, and a fully-scalable architecture.