🔔 Subscribe for more Artificial Intelligence news, Robot news, Tech news and more.

🦾 Support us NOW so we can create more videos: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCItylrp-EOkBwsUT7c_Xkxg.

Every week we will update you about the Robotic news in Japan.

Living Human Skin for Robots.

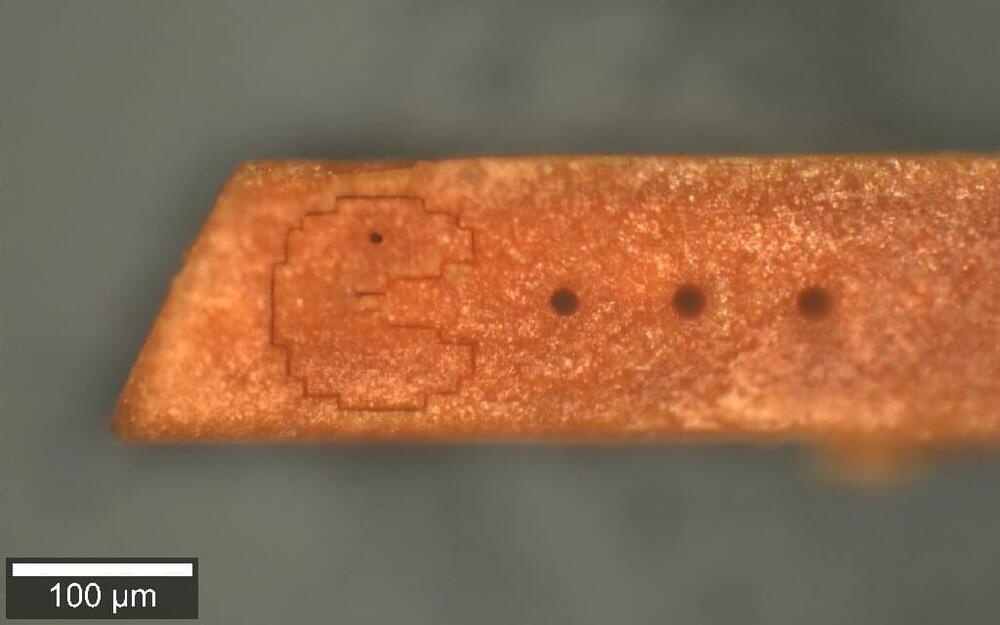

From action heroes to villainous assassins, biohybrid robots made of both living and artificial materials have been at the center of many sci-fi fantasies, inspiring today’s robotic innovations. It’s still a long way until human-like robots walk among us in our daily lives, but scientists from Japan are bringing us one step closer by crafting living human skin on robots. The method developed not only gave a robotic finger skin-like texture, but also water-repellent and self-healing functions. “The finger looks slightly ‘sweaty’ straight out of the culture medium,” says first author Shoji Takeuchi, a professor at the University of Tokyo, Japan. “Since the finger is driven by an electric motor, it is also interesting to hear the clicking sounds of the motor in harmony with a finger that looks just like a real one.“

Looking “real” like a human is one of the top priorities for humanoid robots that are often tasked to interact with humans in healthcare and service industries. A human-like appearance can improve communication efficiency and evoke likability. While current silicone skin made for robots can mimic human appearance, it falls short when it comes to delicate textures like wrinkles and lacks skin-specific functions.

Artificial Intelligence that Acts More Human.

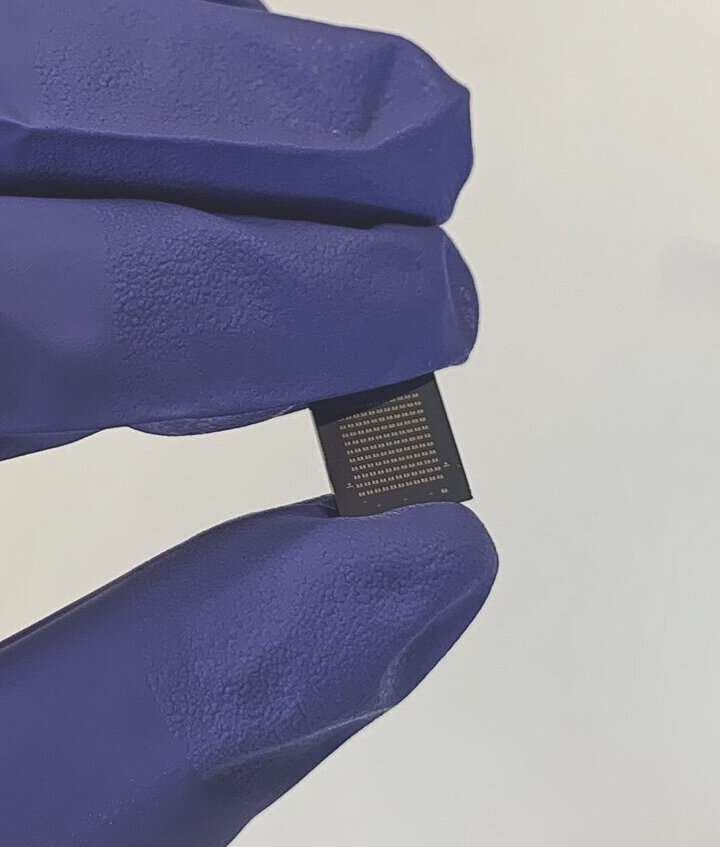

A research group from the Graduate School of Informatics, Nagoya University, has taken a big step towards creating a neural network with metamemory through a computer-based evolution experiment. In recent years, there has been rapid progress in designing artificial intelligence technology using neural networks that imitate brain circuits. One goal of this field of research is understanding the evolution of metamemory to use it to create artificial intelligence with a human-like mind.

Metamemory is the process by which we ask ourselves whether we remember what we had for dinner yesterday and then use that memory to decide whether to eat something different tonight. While this may seem like a simple question, answering it involves a complex process. Metamemory is important because it involves a person having knowledge of their own memory capabilities and adjusting their behavior accordingly.

Smart Robot Helps at Narita Airport.

A robot equipped with artificial intelligence has been put to work to help sort out congestion problems at Narita International Airport near Tokyo. The robot is shaped like a small vehicle and stands about 1.2 meters high. The AI instantly analyzes images taken by its cameras. The robot can quickly grasp how and where congestion occurs. It gives instructions to keep order when it detects long queues blocking the way. The robot also keeps an eye out for suspicious items. It informs the command center when baggage is left unattended for too long.