Previous attempts at building a chemical computer have been too simple, too rigid or too hard to scale, but an approach based on a network of reactions can perform multiple tasks without having to be reconfigured

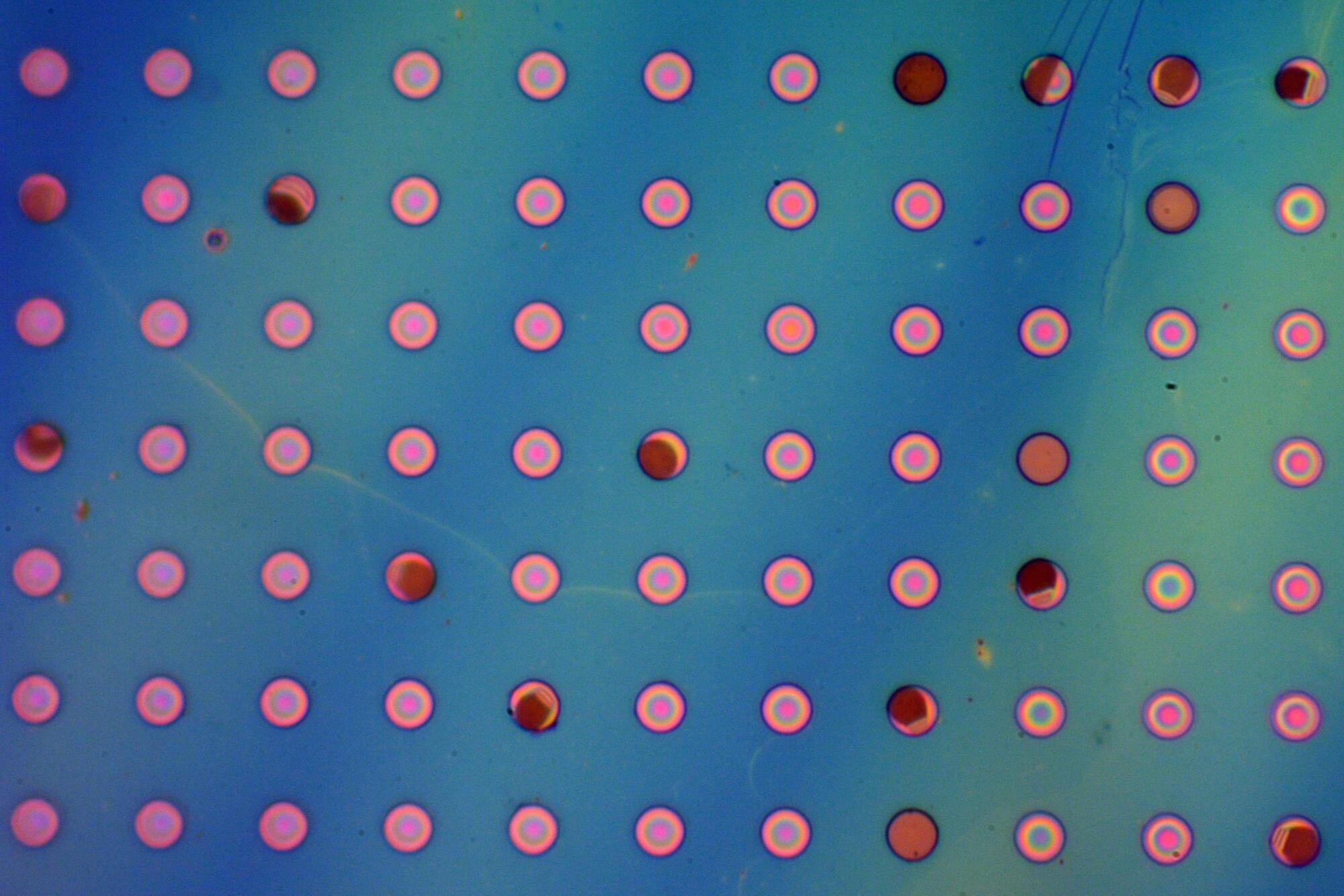

For decades, it’s been known that subtle chemical patterns exist in metal alloys, but researchers thought they were too minor to matter — or that they got erased during manufacturing. However, recent studies have shown that in laboratory settings, these patterns can change a metal’s properties, including its mechanical strength, durability, heat capacity, radiation tolerance, and more.

Now, researchers at MIT have found that these chemical patterns also exist in conventionally manufactured metals. The surprising finding revealed a new physical phenomenon that explains the persistent patterns.

In a paper published in Nature Communications today, the researchers describe how they tracked the patterns and discovered the physics that explains them. The authors also developed a simple model to predict chemical patterns in metals, and they show how engineers could use the model to tune the effect of such patterns on metallic properties, for use in aerospace, semiconductors, nuclear reactors, and more.

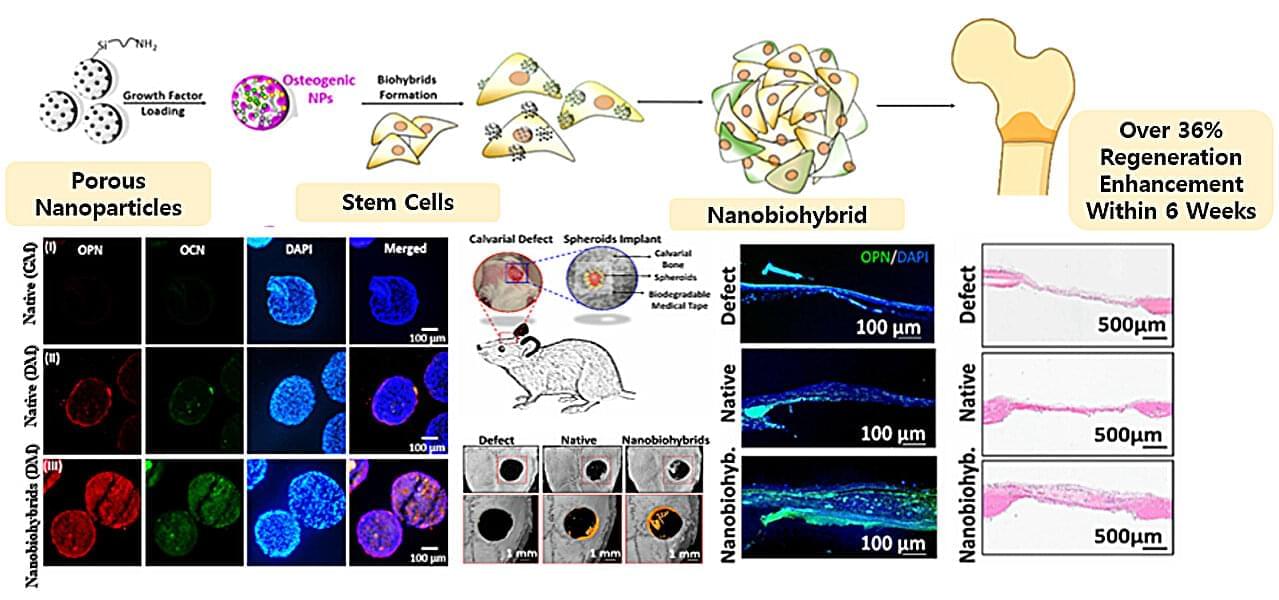

A research team in South Korea has successfully developed a novel technology that combines nanoparticles with stem cells to significantly improve 3D bone tissue regeneration. This advancement marks a step forward in the treatment of bone fractures and injuries, as well as in next-generation regenerative medicine.

The research is published in the journal ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering.

Dr. Ki Young Kim and her team at the Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology (KRICT), in collaboration with Professor Laura Ha at Sunmoon University, have engineered a nanoparticle-stem cell hybrid, termed a nanobiohybrid by integrating mesoporous silica nanoparticles (mSiO₂ NPs) with human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hADMSCs). The resulting hybrid cells demonstrated markedly enhanced osteogenic (bone-forming) capability.

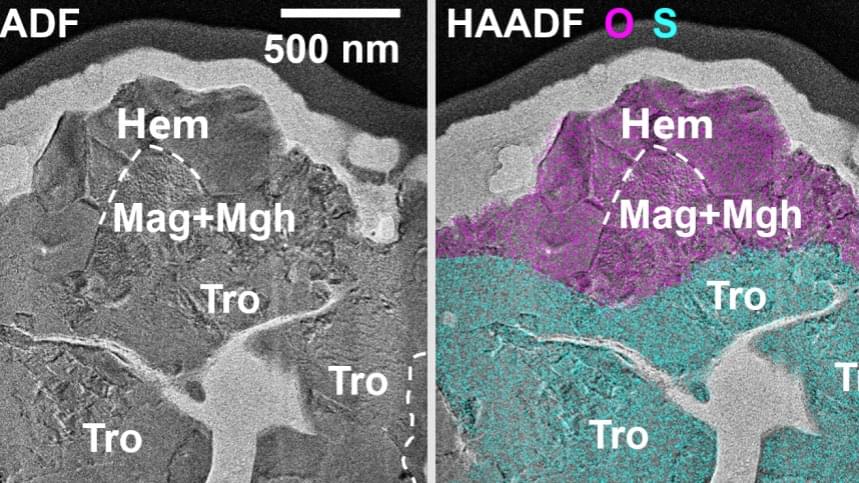

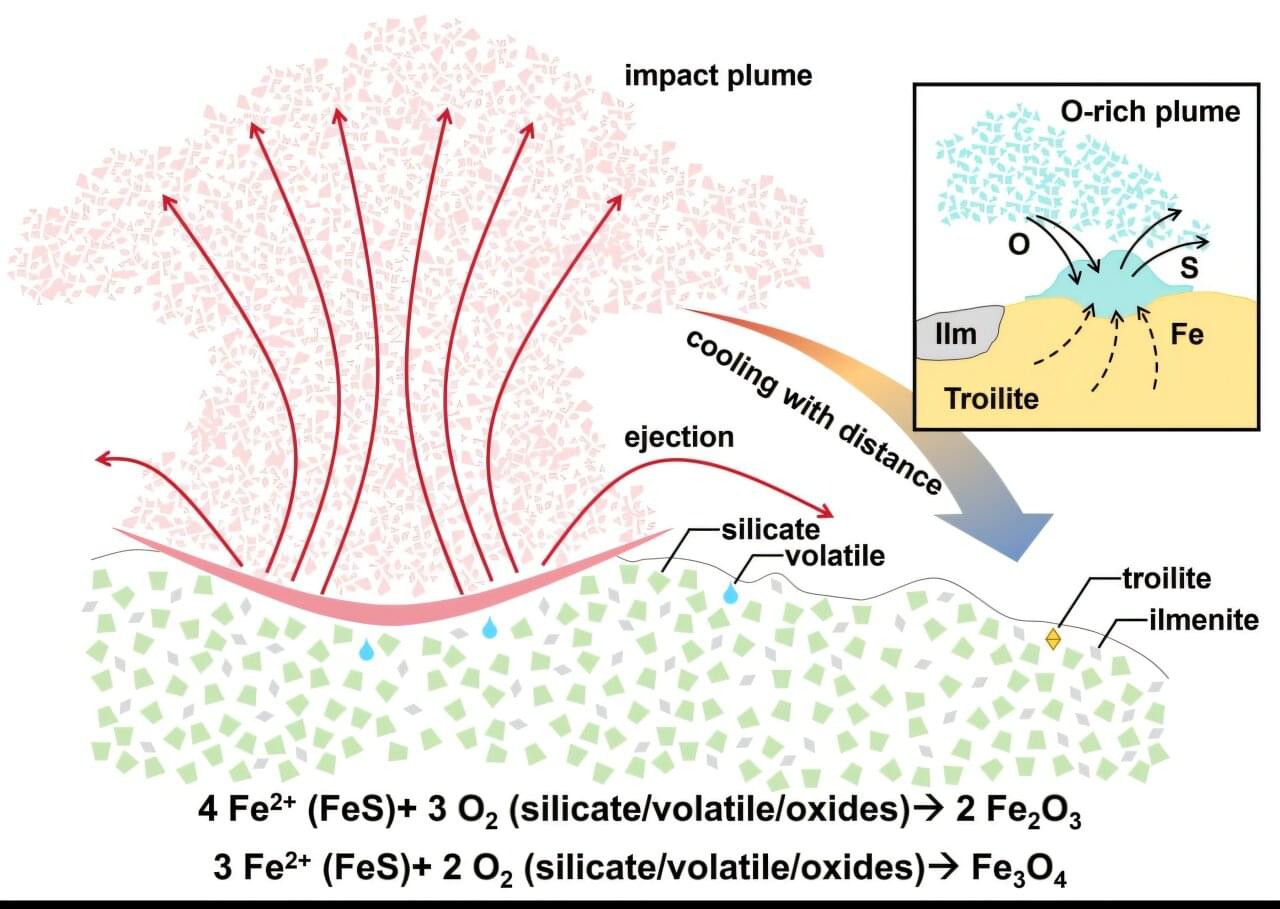

Chinese scientists have, for the first time, identified micrometer-sized crystals of hematite and maghemite in lunar soil samples brought back by the Chang’e 6 mission from the moon’s far side.

This finding, published in the latest issue of the journal Science Advances, reveals a previously unknown oxidation process on the moon. It provides direct sample evidence for the origin of magnetic anomalies around the South Pole-Aitken Basin and challenges the long-standing view that the lunar surface is entirely in a reduced state with minimal oxidation, according to the China National Space Administration.

The research, conducted by Shandong University, the Institute of Geochemistry of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Yunnan University, identified these iron oxides in the Chang’e 6 samples collected from the SPA Basin, the largest and oldest known impact basin in the solar system.

A new water-based plasma technique is opening fresh possibilities for carbon conversion.

Chinese researchers have created stable high-entropy alloy nanoparticles—containing five metals in nearly equal ratios—directly in solution, thereby overcoming long-standing challenges in nanoscale alloy synthesis.

These particles form a self-protecting, oxidized shell, delivering strong photothermal performance that utilizes visible and infrared light to drive carbon dioxide into carbon monoxide more efficiently than single-metal catalysts.

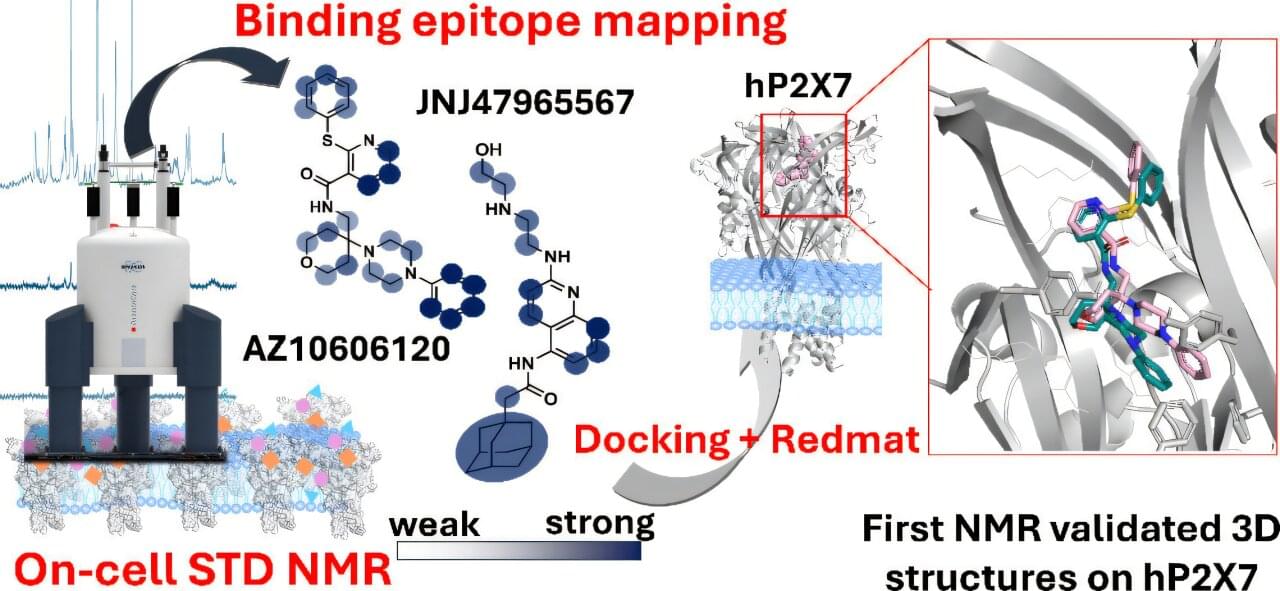

An international team involving the Institute of Chemical Research, a joint center of the University of Seville and the Spanish National Research Council, has developed a new technique that will accelerate the design of drugs that target ion channels, a type of cell membrane protein involved in numerous diseases, ranging from psychiatric disorders to various types of cancer.

The research, carried out in collaboration with the University of East Anglia and the Qadram Institute (both in the United Kingdom), has been published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Ion channels are cell membrane proteins that regulate the passage of ions into the cell. They are essential in processes as diverse as nerve transmission, muscle contraction and immune response and their dysfunction is associated with numerous disorders, making them therapeutic targets of great interest.

A joint research team from the Institute of Geochemistry of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGCAS) and Shandong University has for the first time identified crystalline hematite (α-Fe2O3) and maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) formed by a major impact event in lunar soil samples retrieved by China’s Chang’e-6 mission from the South Pole–Aitken (SPA) Basin. This finding, published in Science Advances on November 14, provides direct sample-based evidence of highly oxidized materials on the lunar surface.

Redox reactions are a fundamental component of planetary formation and evolution. Nevertheless, scientific studies have shown that neither the oxygen fugacity of the lunar interior nor the lunar surface environment favors oxidation. Consistent with this, multivalent iron on the moon primarily exists in its ferrous (Fe2+) and metallic (Fe0) states, suggesting an overall reduced state. However, with further lunar exploration, recent orbital remote sensing studies using visible-near-infrared spectroscopy have suggested the widespread presence of hematite in the moon’s high-latitude regions.

Furthermore, earlier research on Chang’e-5 samples first revealed impact-generated sub-micron magnetite (Fe3O4) and evidence of Fe3+ in impact glasses. These results indicate that localized oxidizing environments on the moon existed during lunar surface modification processes driven by external impacts.

Natural gas—one of the planet’s most abundant energy sources—is primarily composed of methane, ethane, and propane. While it is widely burned for energy, producing greenhouse gas emissions, scientists and industries have long sought ways to directly convert these hydrocarbons into valuable chemicals. However, their extreme stability and low reactivity have posed a formidable challenge, limiting their use as sustainable feedstocks for the chemical industry.

Now, a team led by Martín Fañanás at the Center for Research in Biological Chemistry and Molecular Materials (CiQUS) at the University of Santiago de Compostela has developed a groundbreaking method to transform methane and other natural gas components into versatile “building blocks” for synthesizing high-demand products, such as pharmaceuticals. Published in Science Advances, this advance represents a critical leap toward a more sustainable and circular chemical economy.

For the first time, the CiQUS team successfully synthesized a bioactive compound—dimestrol, a non-steroidal estrogen used in hormone therapy—directly from methane. This achievement demonstrates the potential of their methodology to create complex, high-value molecules from a simple, abundant, and low-cost raw material.

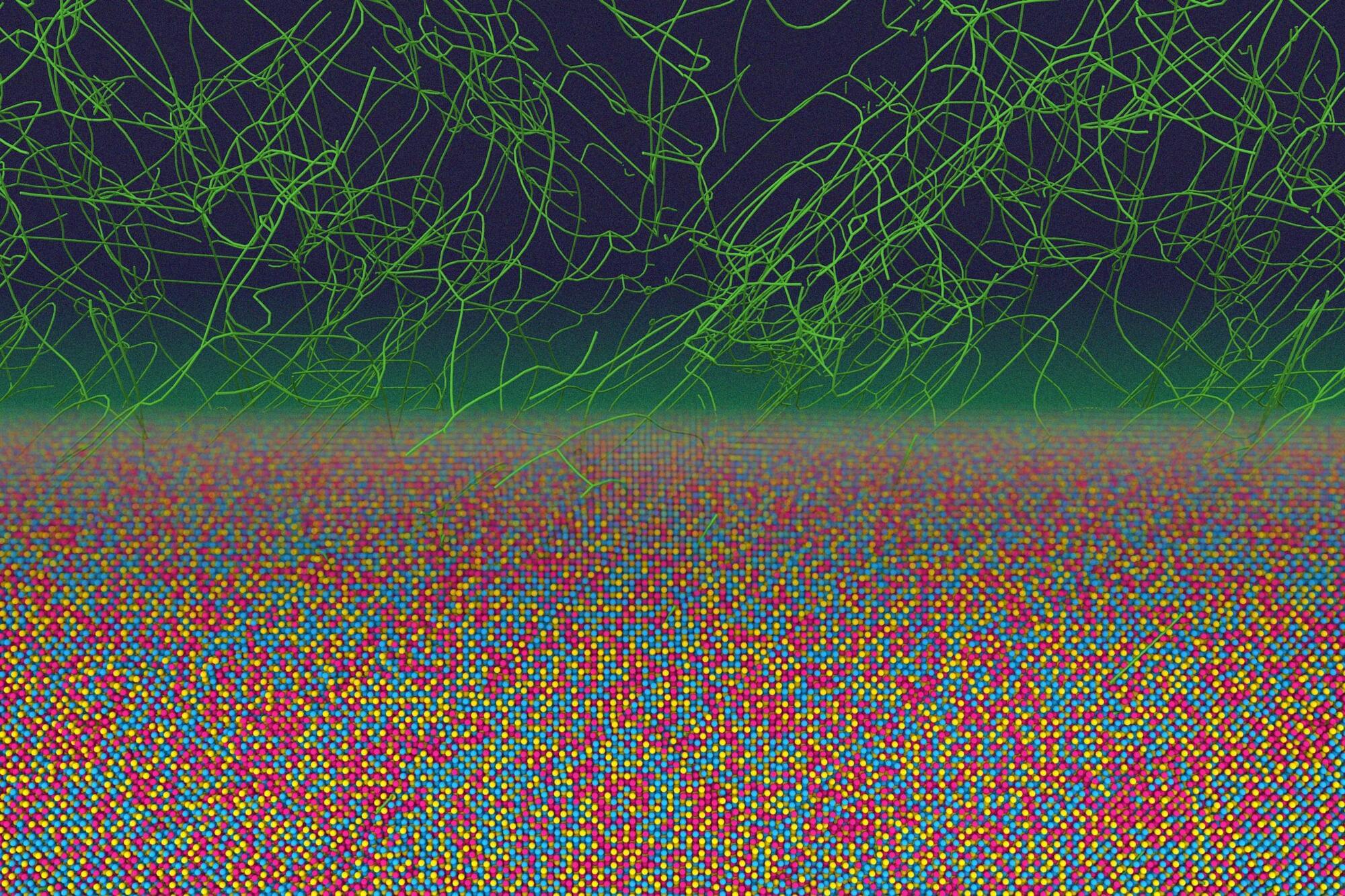

MIT researchers have developed a lightweight polymer film that is nearly impenetrable to gas molecules, raising the possibility that it could be used as a protective coating to prevent solar cells and other infrastructure from corrosion, and to slow the aging of packaged food and medicines.

The polymer, which can be applied as a film mere nanometers thick, completely repels nitrogen and other gases, as far as can be detected by laboratory equipment, the researchers found. That degree of impermeability has never been seen before in any polymer, and rivals the impermeability of molecularly-thin crystalline materials such as graphene.

“Our polymer is quite unusual. It’s obviously produced from a solution-phase polymerization reaction, but the product behaves like graphene, which is gas-impermeable because it’s a perfect crystal. However, when you examine this material, one would never confuse it with a perfect crystal,” says Michael Strano, the Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT.