Nanotechnologist and co-founder of the Black in Nanotech initiative, Olivia Geneus. (Courtesy: Alexander Harold) Welcome to this Physics World Nanotechnology Briefing, which showcases the breadth of applications of modern nanotechnology.

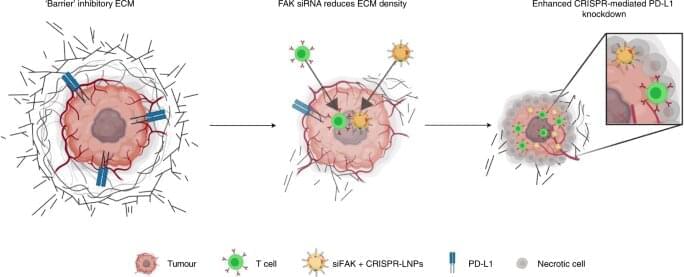

Olivia Geneus is one of the growing number of scientists who are developing nanotechnologies for medicine. In an interview, the PhD student at the State University of New York at Buffalo explains how she is developing nanoparticles designed to cross the blood–brain barrier in order to image and destroy brain cancer cells. Geneus also talks about Black in Nanotech Week, which she co-founded, and the need to encourage Black children to consider careers in science.

Ed Lester of the UK’s University of Nottingham knows that there are myriad uses for nanoparticles. In 2007 he founded the company Promethean Particles when he realized industrial users were not able to source nanoparticles in the quantities and quality that they required. In an interview, Lester talks about some of the company’s development projects including nanoparticles for aviation, healthcare and energy.