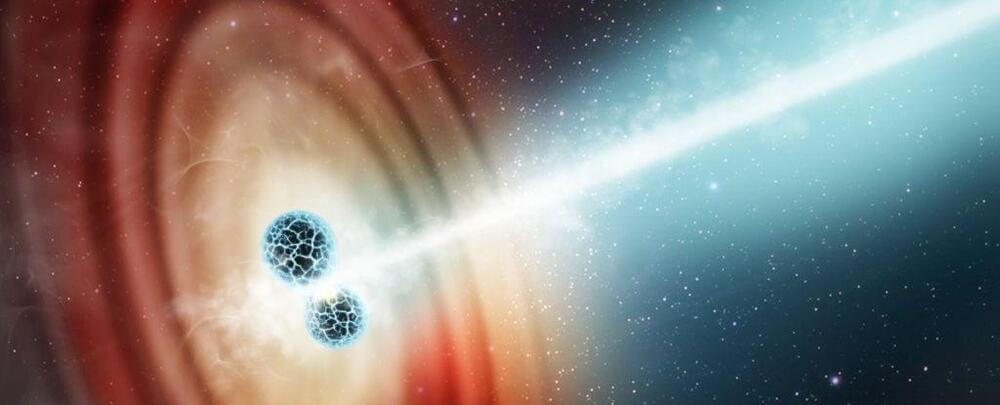

In February 2016, scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) announced the first-ever detection of gravitational waves (GWs). Originally predicted by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, these waves are ripples in spacetime that occur whenever massive objects (like black holes and neutron stars) merge. Since then, countless GW events have been detected by observatories across the globe – to the point where they have become an almost daily occurrence. This has allowed astronomers to gain insight into some of the most extreme objects in the Universe.

In a recent study, an international team of researchers led by Cardiff University observed a binary black hole system originally detected in 2020 by the Advanced LIGO, Virgo, and Kamioki Gravitational Wave Observatory (KAGRA). In the process, the team noticed a peculiar twisting motion (aka. a precession) in the orbits of the two colliding black holes that was 10 billion times faster than what was noted with other precessing objects. This is the first time a precession has been observed with binary black holes, which confirms yet another phenomenon predicted by General Relativity (GR).

The team was led by Professor Mark Hannam, Dr. Charlie Hoy, and Dr. Jonathan Thompson from the Gravity Exploration Institute at Cardiff University. They were joined by researchers from the LIGO Laboratory, the Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, the Institute for Gravitational Wave Astronomy, the ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery, the Scottish Universities Physics Alliance (SUPA), and other GW research institutes.