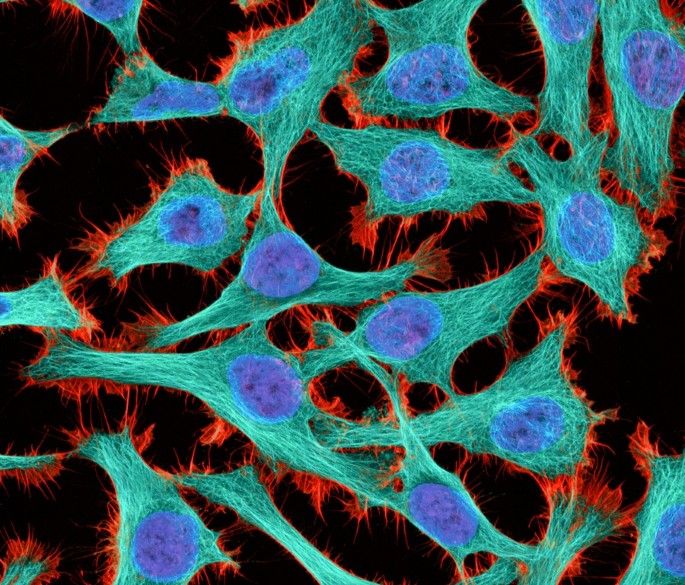

The company has already used AlphaFold, its protein folding AI, to generate structures for nearly all of the human proteome, as well as yeast, fruit flies, mice and more.

Nick Saraev is 25 years old, far too young, it would seem, to be thinking about death. And yet, since he turned 21, he has taken steps to prevent the infirmities of old age. Every day, he takes 2000 mg of fish oil and 4000 IU of vitamin D to help prevent heart disease and other ailments. He steams or pressure-cooks most of his meals because, he says, charring meats creates chemicals that may increase the risk of cancer. And in the winter, he keeps the humidity of his home at 35 percent, because dry air chaps his skin and makes him cough, both of which he considers manifestations of chronic inflammation, which may be bad for longevity.

Based on the life expectancies of young men in North America, Saraev, a freelance software engineer based near Vancouver, believes he has about 55 years before he really has to think about aging. Given the exponential advances in microprocessors and smartphones in his lifetime, he insists the biotech industry will figure out a solution by then. For this reason, Saraev, like any number of young, optimistic, tech-associated men, believes that if he takes the correct preventative steps now, he might well live forever. Saraev’s plan is to keep his body in good enough shape to hit “Longevity Escape Velocity,” a term coined by English gerontologist Aubrey de Grey to denote slowing down your aging enough to reach each new medical advance as it arrives. If you delay your death by 10 years, for example, that’s 10 more years scientists have to come up with a drug, computer program, or robot assist that can make you live even longer. Keep up this game of reverse leapfrog, and eventually death can’t catch you. The term is reminiscent of “planetary escape velocity,” the speed an object needs to move in order to break free of gravity.

The science required to break free of death, unfortunately, is still at ground level. According to Nir Barzilai, M.D., director of the Institute for Aging Research at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, scientists currently understand aging as a function of seven to nine biological hallmarks, factors that change as we grow older and seem to have an anti-aging effect when reversed. You can imagine these as knobs you can turn up or down to increase or decrease the likelihood of illness and frailty. Some of these you may have heard of, including how well cells remove waste, called proteostasis; how well cells create energy, or mitochondrial function; how well cells implement their genetic instructions, or epigenetics; and how well cells maintain their DNA’s integrity, called DNA repair or telomere erosion.

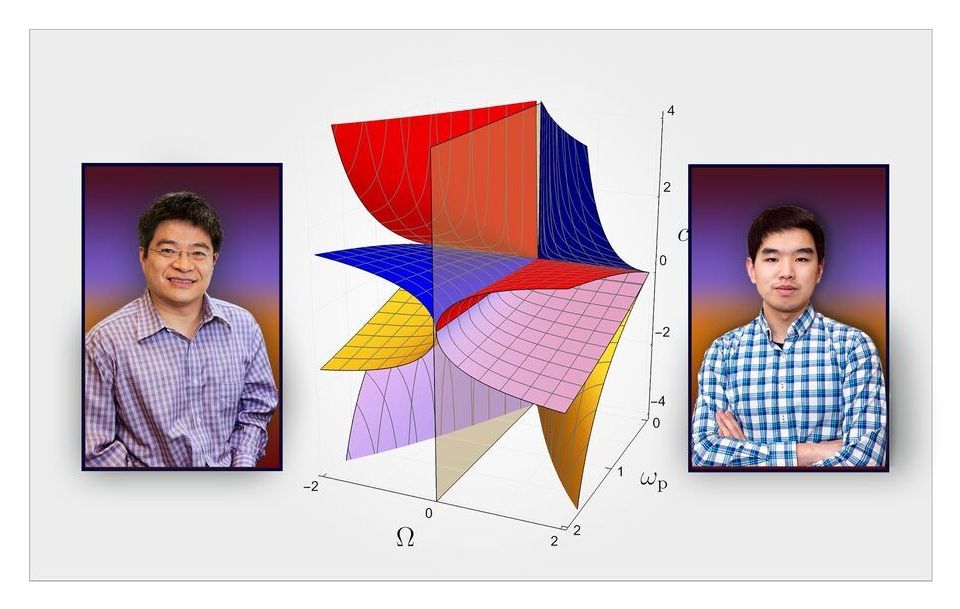

Scientists have discovered a novel way to classify magnetized plasmas that could possibly lead to advances in harvesting on Earth the fusion energy that powers the sun and stars. The discovery by theorists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) found that a magnetized plasma has 10 unique phases and the transitions between them might hold rich implications for practical development.

The spatial boundaries, or transitions, between different phases will support localized wave excitations, the researchers found. “These findings could lead to possible applications of these exotic excitations in space and laboratory plasmas,” said Yichen Fu, a graduate student at PPPL and lead author of a paper in Nature Communications that outlines the research. “The next step is to explore what these excitations could do and how they might be utilized.”

Two teams of researchers took part in the dramatic discovery, published in the prestigious Science journal: an anthropology team from Tel Aviv University headed by Prof. Israel Hershkovitz, Dr. Hila May and Dr. Rachel Sarig from the Sackler Faculty of Medicine and the Dan David Center for Human Evolution and Biohistory Research and the Shmunis Family Anthropology Institute, situated in the Steinhardt Museum at Tel Aviv University; and an archaeological team headed by Dr. Yossi Zaidner from the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Timeline: The Nesher Ramla Homo type was an ancestor of both the Neanderthals in Europe and the archaic Homo populations of Asia.

Prof. Israel Hershkovitz: “The discovery of a new type of Homo” is of great scientific importance. It enables us to make new sense of previously found human fossils, add another piece to the puzzle of human evolution, and understand the migrations of humans in the old world. Even though they lived so long ago, in the late middle Pleistocene (474000−130000 years ago), the Nesher Ramla people can tell us a fascinating tale, revealing a great deal about their descendants’ evolution and way of life.”

The Jerusalem Post.

Hebrew U and Tel Aviv University researchers found remains of a new type of ‘Homo’ who lived in the region some 130000 years ago.

This product came out months ago with some shocking numbers as to effect. But those effects were in mice tests. 10–20% increase in lifespan and 55% increase in healthspan. It is AKG, Rejuvant, it’s a product you can buy now. There will be a part 2 of this interview so I hope to hear about human data.

Here we present an interview with Tom Weldon the founder and CEO of Ponce de Leon Health, which makes Rejuvant a Calcium AKG based supplement. In this video Tom talks through the process and reasons for selecting CaAKG. He also talks about some of the other results that they found in their tests, especially with respect to mixing different supplements and their combined effects.

This it part 1 of a two part series. In part 2 we talk about his personal experience and on going clinical trials. With that let me start the interview.

Links to Rejuvant.

https://www.rejuvant.com/

Ponce de Leon Health.

The paper from the Buck institute mentioned in the call.

The World Health Organization classifies processed meat as a Group 1 carcinogen. Processed meat includes ham, sausage, bacon, pepperoni; they’re meats that have been preserved with salt or smoke, meat that has been cured, and meat treated with chemical preserves. Other Group 1 carcinogens include formaldehyde, tobacco, and UV radiation. Group 1 carcinogens have ‘enough evidence to conclude that it can cause cancer in humans.’

There is no question whether or not our current meat production complex is inhumane, unsanitary, or bad for the environment. Almost all chickens (99.9%), turkeys (99.8%), and most cows (70.4%) eaten in the United States are raised on factory farms. There are horrific consequences to this practice.

For example, the EPA estimates agriculture is the biggest contaminator of rivers and streams, to the point where feedlots, crop production, and manure runoff have led almost half (46%) of the U.S.’s rivers to be “in poor biological condition.”

Scientific American also explains, “TDM-approved feed containing antibiotics [are] a necessity if [factory farm animals] were to stay healthy in their crowded, manure-gilded home. Antibiotics also help farm animals grow faster on less food, so their use has long been a staple of industrial farming.” Many scientists worry that antibiotics used at such a scale on farms create unstoppable, drug-resistant bacteria that can transfer to humans; think inconveniences like nose infections or UTIs turned deadly because of the lack of antibiotics available to treat them.

The Science of Aliens, Part III: Have they overcome their savage past or might they want to eat us?

Reviewing our own species’ behavior suggests a cautious approach to contact with extraterrestrials.

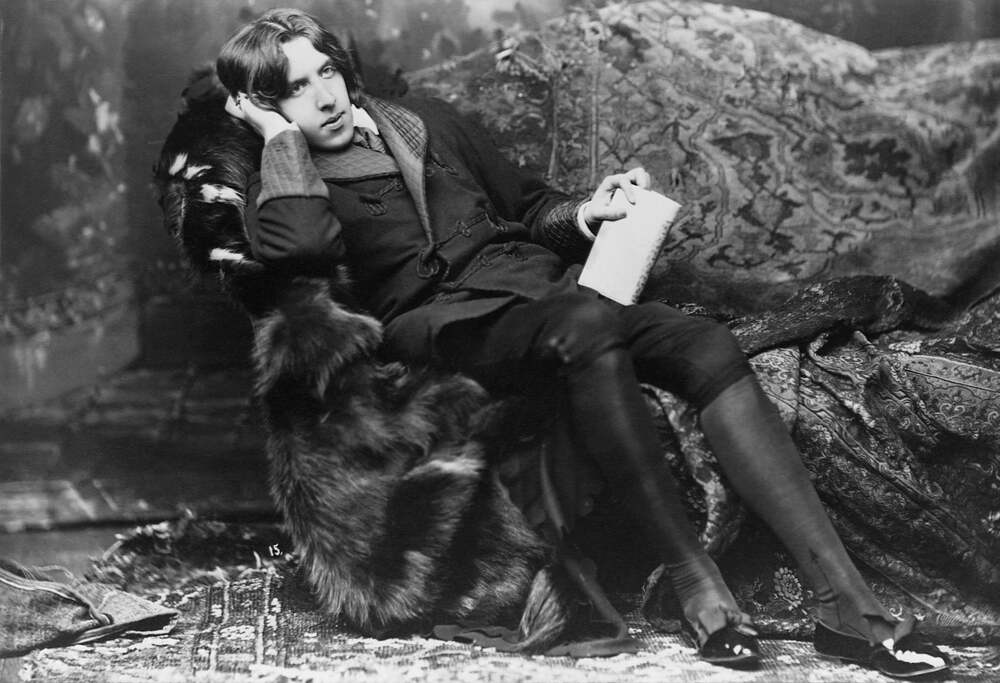

Both arts and sciences advance through open-minded iterations. The alternative of staying within traditional boundaries suppresses the exploration of new territories. As Oscar Wilde said: “Consistency is the last refuge of the unimaginative.”

Recognizing the crucial role that imagination plays in advancing both arts and sciences would translate to a culture that fosters innovation by rewarding creativity. Conventional groupthink could be circumvented by populating selection committees of funding agencies with creative individuals rather than with traditional thinkers. A culture of innovation would also benefit from overlap spaces where scientists and artists interact. In deriving his theory of gravity Albert Einstein was inspired by the philosopher Ernst Mach, and Einstein’s new notions of space and time inspired Picasso’s paintings.

Creativity in arts and sciences establishes a backdrop for human existence, as the content it invents gives pleasure and meaning to our lives. The human act of creation is an infinite-sum game, from which all of us benefit. And we can all participate in the creative process, as long as we follow Wilde’s advice: “Be yourself; everyone else is already taken.”